Messier Monday: The brightest Messier globular, M22

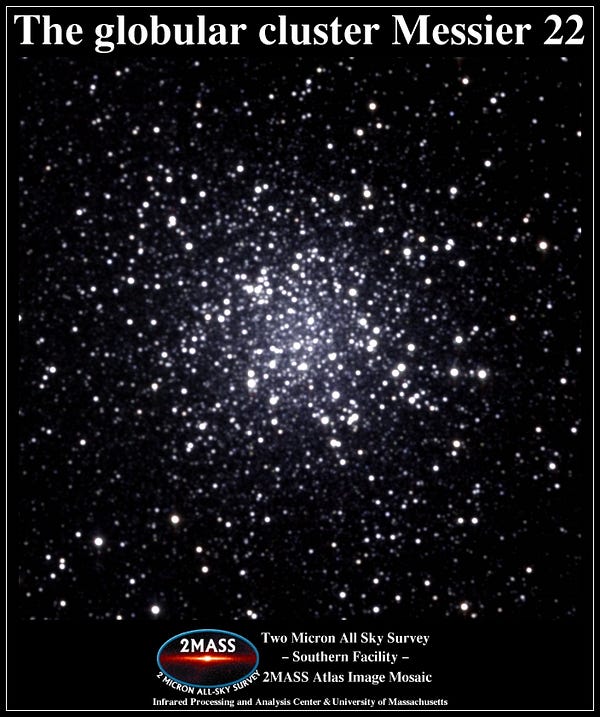

With a planetary nebula, over 80,000 stars and a distance of only 10,000 light-years, it’s one of the most rewarding globulars of all!

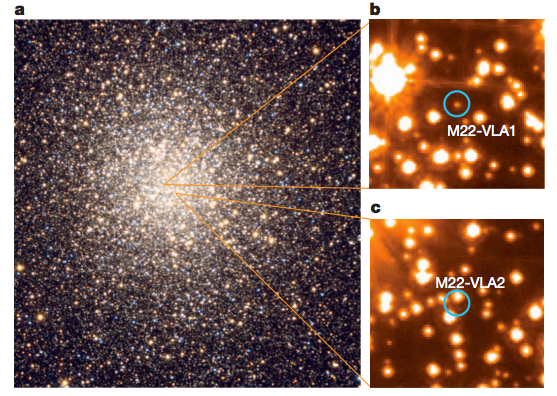

Image credit: R. Columbari, via http://asterisk.apod.com/viewtopic.php?t=31833.

“I love the sea’s sounds and the way it reflects the sky. The colours that shimmer across its surface are unbelievable.” –John Dyer

When you look out at the deep-sky objects in the sky, whether nebulae, star clusters or distant galaxies, one of the things that first-time skywatchers find most surprising is how faint these wondrous sights look through an eyepiece. In particular, the nebulae and galaxies appear more diffuse and faint than people expect, particularly given the long-exposure astrophotos that they’re used to. Perhaps this is something you’ve experienced yourself, looking through a telescope, at one of the many wonders of the Messier catalogue.

Although they may be intrinsically quite bright, their great distances combined with the very large, continuous surface area that their brightness is spread over makes them appear less spectacular than photos would lead you to suspect. But the closest objects — the star clusters within our galaxy — can appear far more spectacular to a casual observer.

While globular clusters tend to be significantly farther away than the open star clusters, the brightest ones provide an absolute feast for the avid astronomer, and Messier 22 — the brightest Messier globular of them all — is perhaps the most classic example. Here’s how to find it.

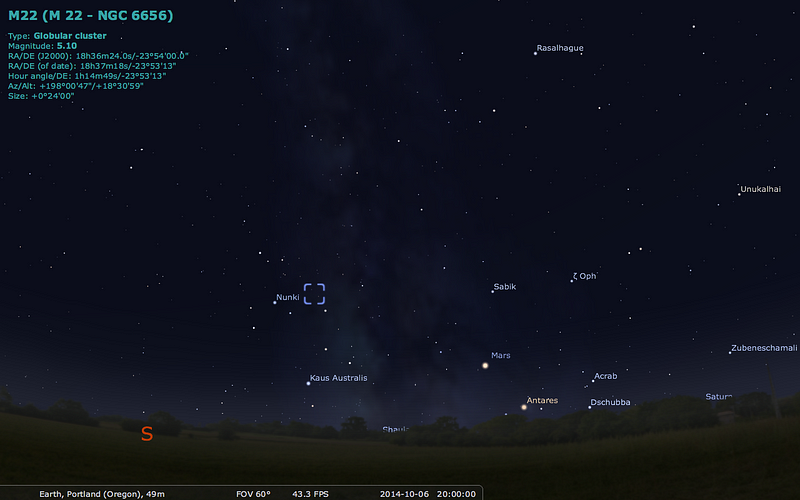

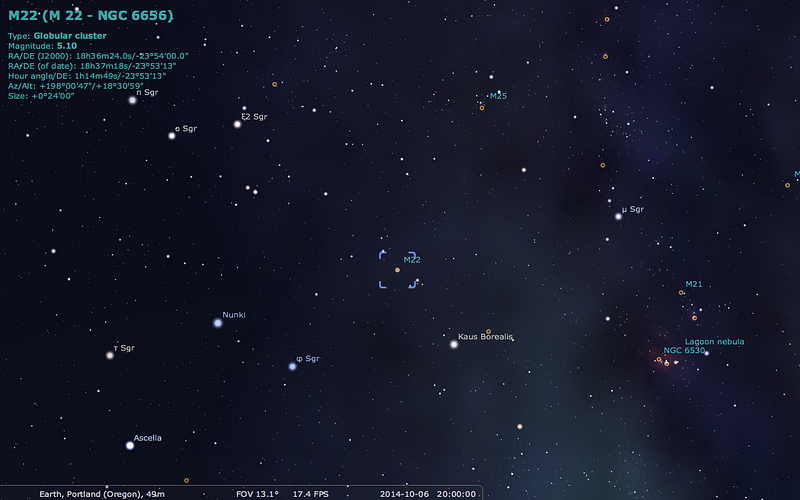

The onset of northern hemisphere winter brings with it dark skies quite early in the night; at high northern latitudes you’ll achieve total darkness by 8 PM local time. Despite the fact that Sagittarius is very much a summer constellation, it’s quite visible even as late as October, with the famed teapot-like collection of stars prominent just above the southern horizon in the early part of the night. As this region of space is very close to the galactic center, there are many deep-sky objects to keep an eye out for, but to find Messier 22, focus on the “top” of the teapot.

The four stars of the handle, shown at the bottom-left of the image above, will guide you to a number of deep sky wonders, as will the three stars at the top-left, all members of Sagittarius. But it’s the very apex of the teapot — the star Kaus Borealis — that will guide you to Messier 22.

Simply draw an imaginary line connecting Kaus Borealis to the westernmost of those three stars “behind” the teapot, ξ Sagittarii, which is actually an easily-split double star. If you navigate from Kaus Borealis and go just shy of 3° towards ξ Sagittarii, it’ll be unmistakable.

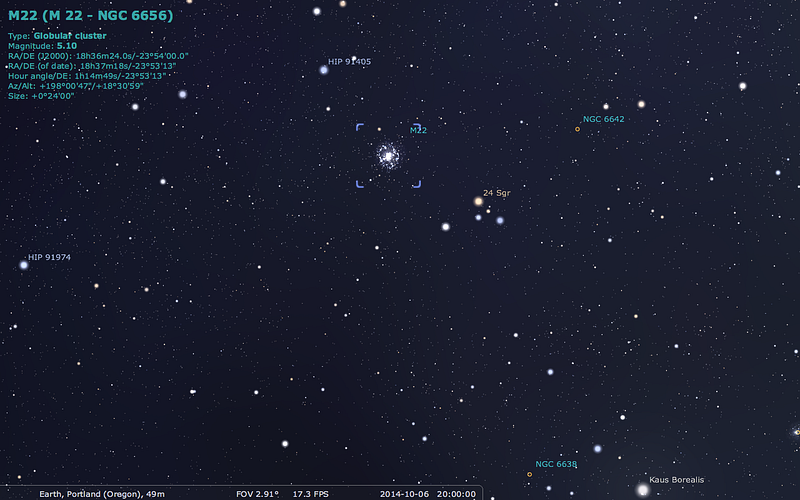

Appearing almost midway between a bluish-white star and a red one of nearly equal brightnesses, Messier 22 stands out as a brilliant, round object with a bright core that fades away as you move farther out. According to Messier himself, it’s a:

Nebula, below the ecliptic, between the head and the bow of Sagittarius, near a star of 7th magnitude, 25 Sagittarii, according to Flamsteed, this nebula is round, it doesn’t contain any star, & one can see it very well in an ordinary telescope…

And so can you.

Of all the known globular clusters, this one has the honor of being the very first discovered, by Abraham Ihle all the way back in 1665! While pretty much all globular clusters are giant collections of tens-to-hundreds-of-thousands of stars, most of which formed more than ten billion years ago, there are a few properties of Messier 22 that make it a unique treat for observers here on Earth.

One is that Messier 22 is extremely close to the ecliptic, meaning that it’s quite frequent that planets come very close to it. Above is Jupiter’s near-conjunction with this globular in 1996, and in fact that’s how Ihle discovered it all the way back those 3½ centuries ago: observing Saturn during a chance conjunction with this cluster!

A second is that while globular clusters are distributed in roughly a halo centered on the galaxy’s core, this one is extremely close to us on a galactic scale. While there are 29 globular clusters in the Messier catalogue (and about 150-to-200 in the galaxy total), only one of them — Messier 4 — is closer to us that today’s object!

In fact, Messier 4 was the first globular resolvable into stars (by Messier), but at a distance of only 10,600 light-years (with an uncertainty of about 1,000 light years), Messier 22 is just 47% farther away than its close cousin, and its stars are clearly visible through most small telescopes today.

A third is that, despite being located in the direction of the galactic center, it’s also located along a relatively dust-free line-of-sight. (Yes, there’s some, but not so much.) While it’s more spectacular from more southerly locations where it rises higher above the horizon, the cluster itself appears little different in the visible from the infrared. Sure, different stars are prominent, which you’d expect since infrared and visible measure different temperatures, but very few new stars appear entirely, which is what would happen if dust were significant. This teaches us that the effect of extinction due to dust is small, and our path to M22 is relatively clear.

In some ways, the cluster is fairly typical of globulars in our galaxy:

- It contains about 3.2% the heavy elements in our Sun,

- It’s dated at about 12 billion years old,

- It contains 32 known variable stars,

- It’s of average concentration — Class VII — on a scale of I to XII,

- Its mass is around 300,000 Suns, and

- It spans about 100 light-years in diameter at its estimated distance.

But its very close proximity to us gives us the opportunity to discover things that may be common in globular clusters, but that are extremely difficult to detect.

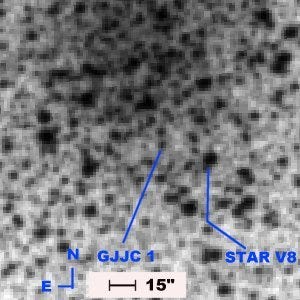

Near the center of the globular cluster is the object identified as IRAS 18333–2357 (or GJJC1, labelled above), which is one of only four planetary nebulae ever found in a globular cluster. Formed from a dying Sun-like star that blows off its outer layers after burning through its fuel in its giant phase, this nebula exhibits a strong signature of doubly-ionized oxygen (O[III]), and yet is very rare for planetary nebulae in that it seems to be totally devoid of hydrogen. The age of the nebula is estimated, based on its size and the luminosity of its main star, to be only 6,000 years old.

Considering there are at least 83,000 stars in Messier 22 (at last count), there was only a chance of a few percent that we’d be serendipitous enough to find a planetary nebula in there at this point in time. But there’s another recent discovery that’s even more world-changing.

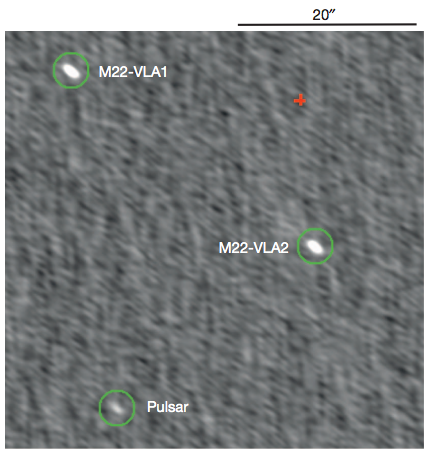

Just two years ago, astronomers working at the Very Large Array were searching for signals of a massive black hole at the center of this cluster. Other globulars have been found with them, and they’re theorized to be at the center of virtually all galaxies, so why not here as well? Gravitational and frictional effects should have brought all of these black holes together at the cluster center, certainly after 12 billion years!

But what they found were stellar mass black holes instead: two of them, with one about 0.8 light-years and the other 1.4 light-years from the cluster’s center. These are only visible because they’re actively feeding off of companion stars, and comparisons of those locations with X-ray observations from Chandra gives us the black hole masses: between 10-and-20 solar masses. This early data is suggestive of the fact that — given how rare feeding black holes are — there might be as many as 100 black holes in this globular cluster, and hence, possibly most globular clusters too!

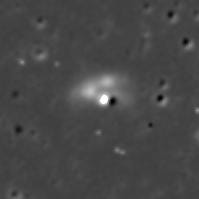

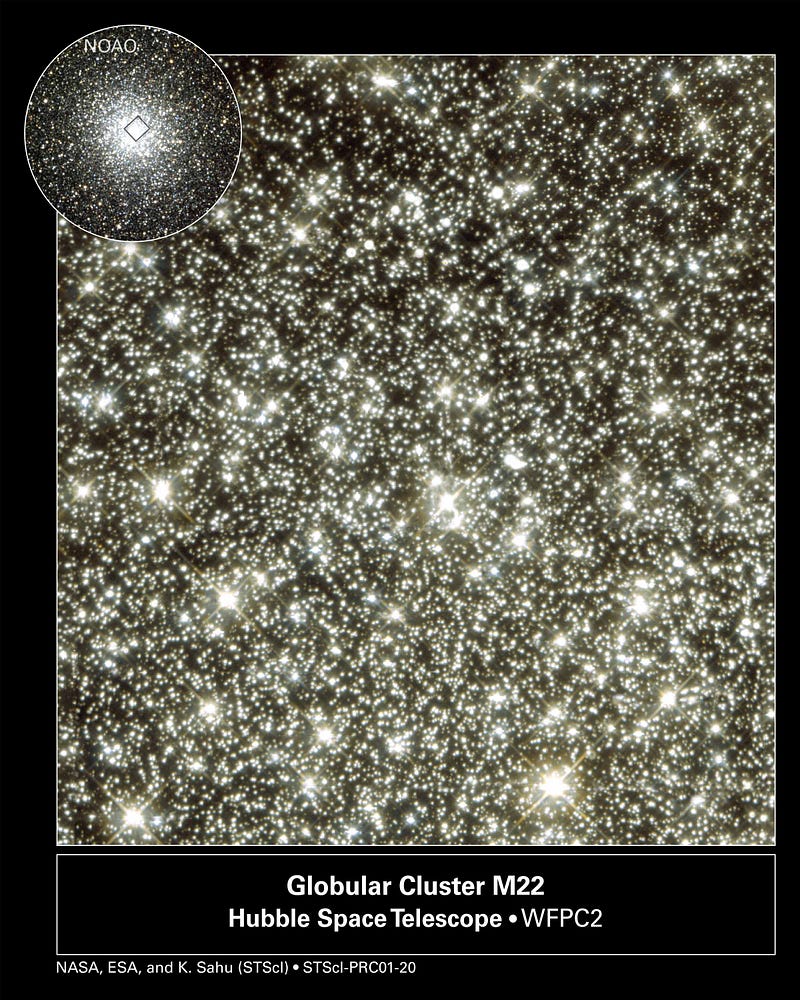

But perhaps most spectacularly, this globular is close enough to us that we can use the Hubble Space Telescope to not only monitor those 83,000 individual stars inside, but they can look for increases in brightness among those stars. This would be expected if there were intervening, rogue planets passing along the line-of-sight between us and the stars, with gas giant-sized planets capable of causing the hypothetical, transient brightness Hubble would see. What did they find?

From February 22 to June 15, 1999, Hubble’s Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 looked through this central region and monitored 83,000 stars. During that time the orbiting observatory recorded six unexpectedly brief microlensing events. In each case a background star jumped in brightness for less than 20 hours before dropping back to normal. These transitory spikes in brightness mean that the object passing in front of the star must have been much smaller than a normal star. Hubble also detected one clear microlensing event. In that observation a star appeared about 10 times brighter over an 18-day span before returning to normal. Astronomers traced the leap in brightness to a dwarf star in the cluster floating in front of the background star.

In other words, rogue planets, or planets without a parent star to call their home, may be extremely common in globular clusters. (Alternately, these stars may have massive exoplanets around them, some of which just happen to be fortuitously aligned along our line-of-sight.)

At full-resolution, the Hubble image of this cluster is spectacular.

All of which is to say, this is the final globular cluster left in the Messier catalogue, and the perfect one to leave you with as Messier Monday approaches its end. With just seven objects left, why don’t you take a look back at all our previous Messier Mondays here:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M4, A Cinco de Mayo Special: May 5, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M6, The Butterfly Cluster: August 18, 2014

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M9, A Globular from the Galactic Center: July 7, 2014

- M10, A Perfect Ten on the Celestial Equator: May 12, 2014

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M14, The Overlooked Globular: June 9, 2014

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M19, The Flattened Fake-out Globular: August 25, 2014

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M22, The Brightest Messier Globular: October 6, 2014

- M23, A Cluster That Stands Out From The Galaxy: July 14, 2014

- M24, The Most Curious Object of All: August 4, 2014

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M27, The Dumbbell Nebula: June 23, 2014

- M28, The Teapot-Dome Cluster: September 8, 2014

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M49, Virgo’s Brightest Galaxy: March 3, 2014

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M54, The First Extragalactic Globular: September 22, 2014

- M55, The Most Elusive Globular Cluster: September 29, 2014

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M58, The Farthest Messier Object (for now): April 7, 2014

- M59, An Elliptical Rotating Wrongly: April 28, 2014

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M61, A Star-Forming Spiral: April 14, 2014

- M62, The Galaxy’s First Globular With A Black Hole: August 11, 2014

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M68, The Wrong-Way Globular Cluster: March 17, 2014

- M69, A Titan in a Teapot: September 1, 2014

- M70, A Miniature Marvel: September 15, 2014

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M80, A Southern Sky Surprise: June 30, 2014

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M84, The Galaxy at the Head-of-the-Chain, May 26, 2014

- M85, The Most Northern Member of the Virgo Cluster, February 10, 2014

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M87, The Biggest One of them All, March 31, 2014

- M88, A Perfectly Calm Spiral in a Gravitational Storm, March 24, 2014

- M89, The Most Perfect Elliptical, July 21, 2014

- M90, The Better-You-Look, The Better-It-Gets Galaxy, May 19, 2014

- M91, A Spectacular Solstice Spiral, June 16, 2014

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M98, A Spiral Sliver Headed Our Way, March 10, 2014

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M100, Virgo’s Final Galaxy, July 28, 2014

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M105, A Most Unusual Elliptical: April 21, 2014

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M107, The Globular that Almost Didn’t Make it: June 2, 2014

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

And come back next week for one of the most glorious sights in the deep-sky, a perfect treat for your October nights!

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs!