Messier Monday: The Better-You-Look, The Better-It-Gets Galaxy, M90

In the heart of our nearest big galaxy cluster, a massive spiral fights for its life.

“Ali always said I would be nothing without him. But what would he have been without me?” –Joe Frazier

When it comes to the deep-sky wonders of the Universe visible from Earth — clusters, nebulae and galaxies — most of them are relatively quiet, peaceful places, not unlike our own stellar neighborhood. Stars in clusters burning through their fuel slowly, only rarely experiencing a gravitational interaction that threatens to rip them apart; galaxies typically have only a few small regions that are forming new stars, and only uncommonly are found in the midst of gravitational interactions; most nebulae are simple clouds of gas, the majority of which simply either reflects or emits light. But every once in a while, we come across a distant object in the Universe that’s fighting for its life.

As the summer months approach and the hours of darkness near their minimum from the Northern Hemisphere, you learn to relish the clear, dark, moonless time you have during nights like tonight. And that makes it the perfect opportunity to check out not only the faint, extended nebulous objects in the Universe, but to go after the ones that reveal even more spectacular details about themselves the deeper you look. For today’s Messier Monday, let’s dive deep inside the Virgo Cluster and check out one of its most spectacular surviving spirals: Messier 90.

Here’s how to find it.

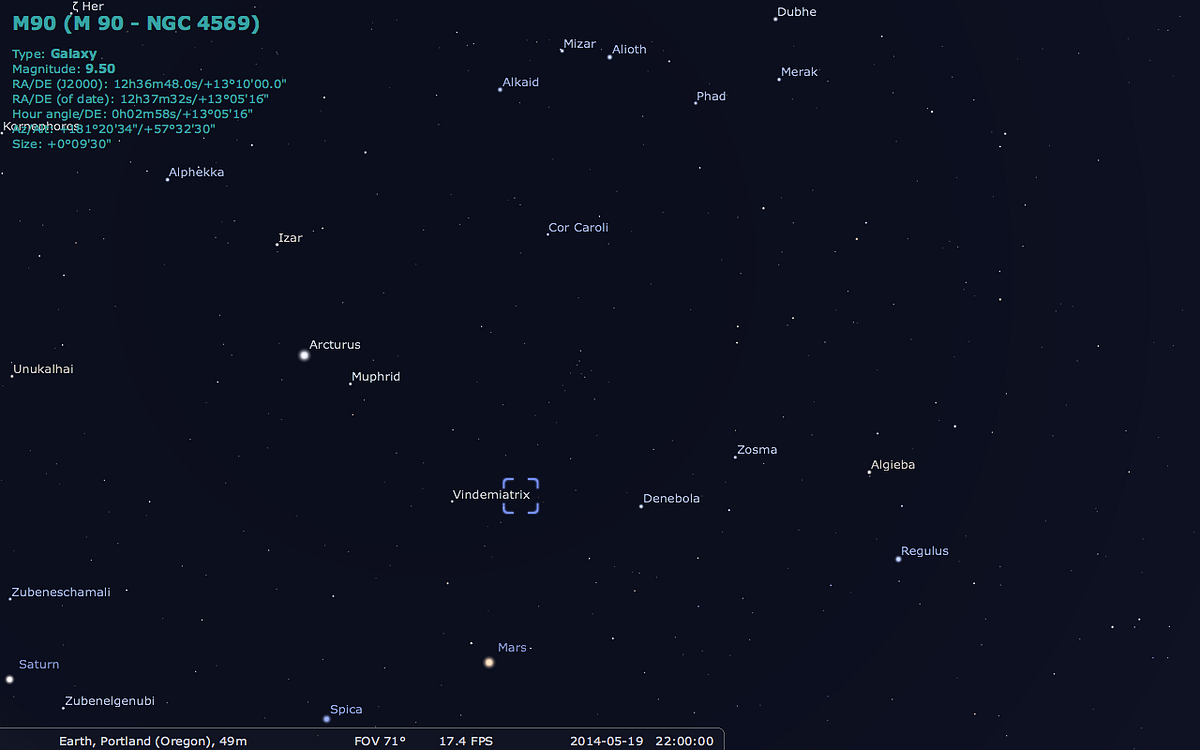

From the northern hemisphere, the easily-recognizable Big Dipper now flies high above the horizon even immediately after sundown, with the prominent constellation of Leo located “underneath” the dipper. The brightest and second-brightest stars of Leo are Regulus and Denebola, respectively, and if you follow the line connecting them, you’ll arrive at Vindemiatrix as well: a bit dimmer but still easily seen even from light-polluted skies.

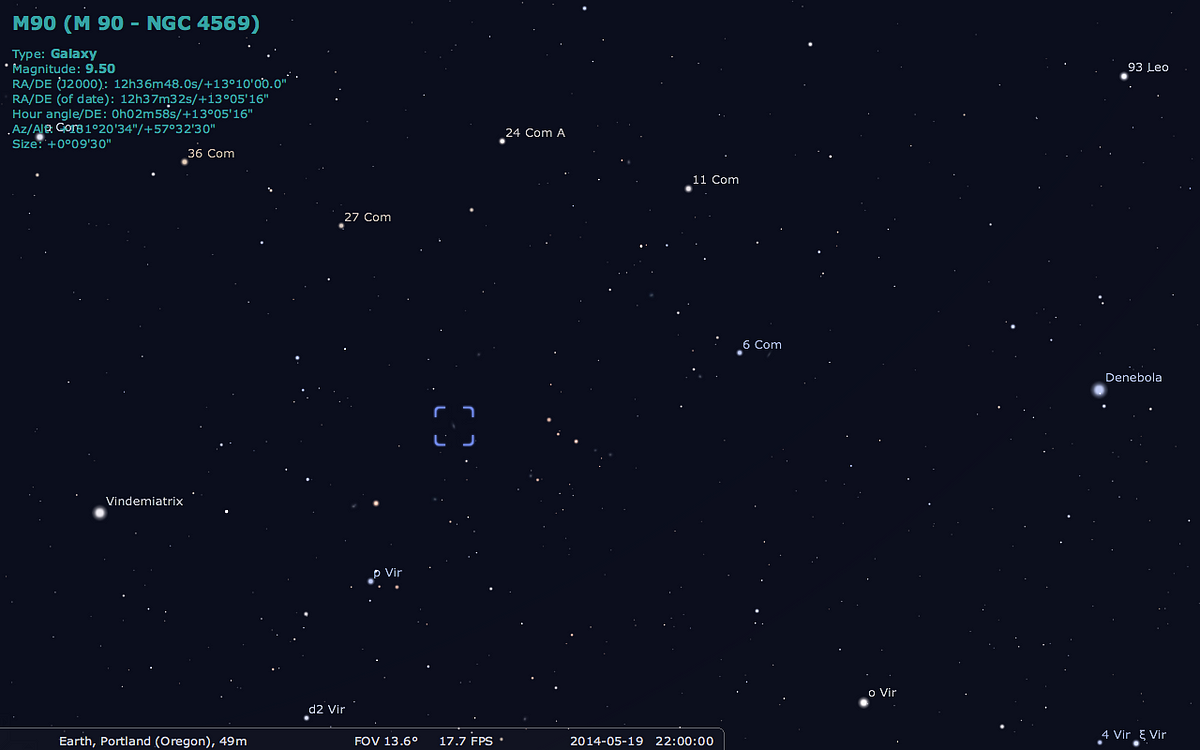

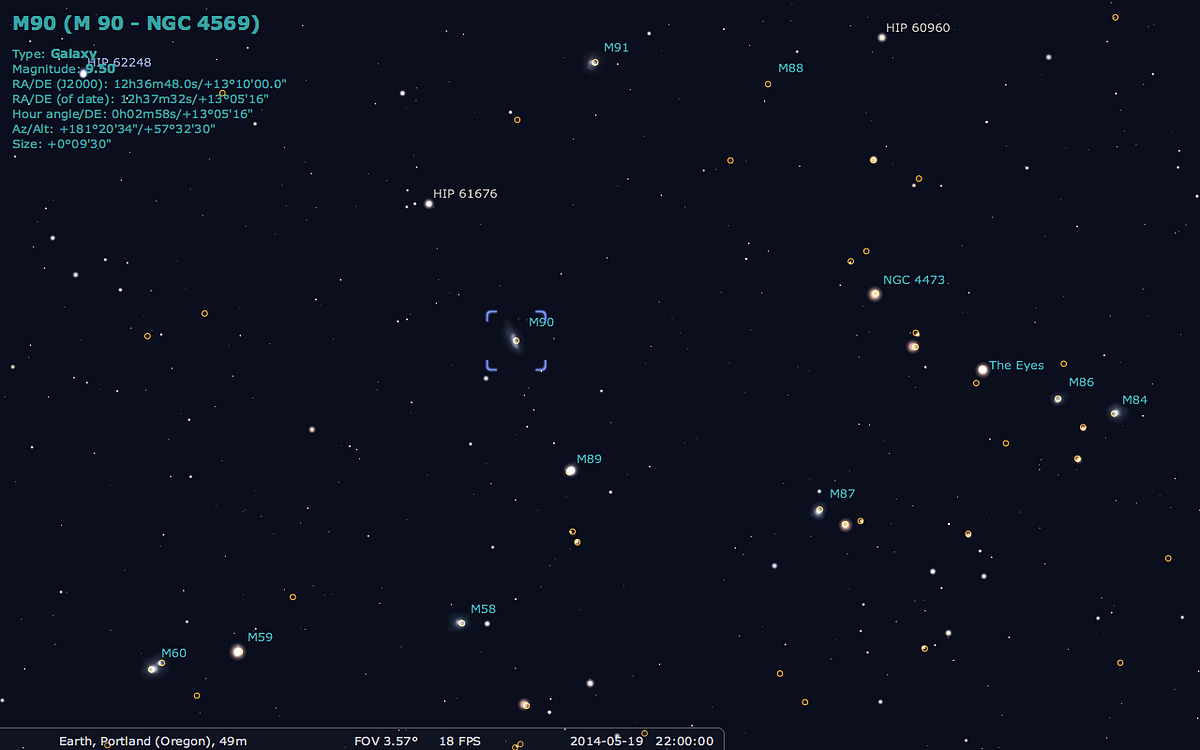

It’s in between Denebola and Vindemiatrix that you can locate not only Messier 90, but also the vast majority of the prominent galaxies in the Virgo Cluster. About a third of the way along the imaginary line connecting Vindemiatrix to Denebola — right where another imaginary line connecting the dim-but-naked-eye stars 24 Comae Berenices and ρ Virginis intersects it — there really isn’t anything that stands out to the naked eye. But if you train either a pair of binoculars or a low-powered telescope on that region, a number of faint things, some of them stars and some of them galaxies, will pop out at you.

As far as stars go, the brightest one you’re likely to encounter in that patch of space is the 7th-magnitude HIP 61676, a relatively insignificant orange star that’s invisible to the naked eye to all but the keenest observers under supremely dark skies. But — despite what the above illustration shows — stars will definitely stand out more than anything else in a field like this. And Messier 90 is just a single degree away from it!

Here’s what a long-exposure image of (roughly) that same wide-field patch of sky — with the 7th-magnitude star cropped out — looks like. Messier 90 is at the upper left.

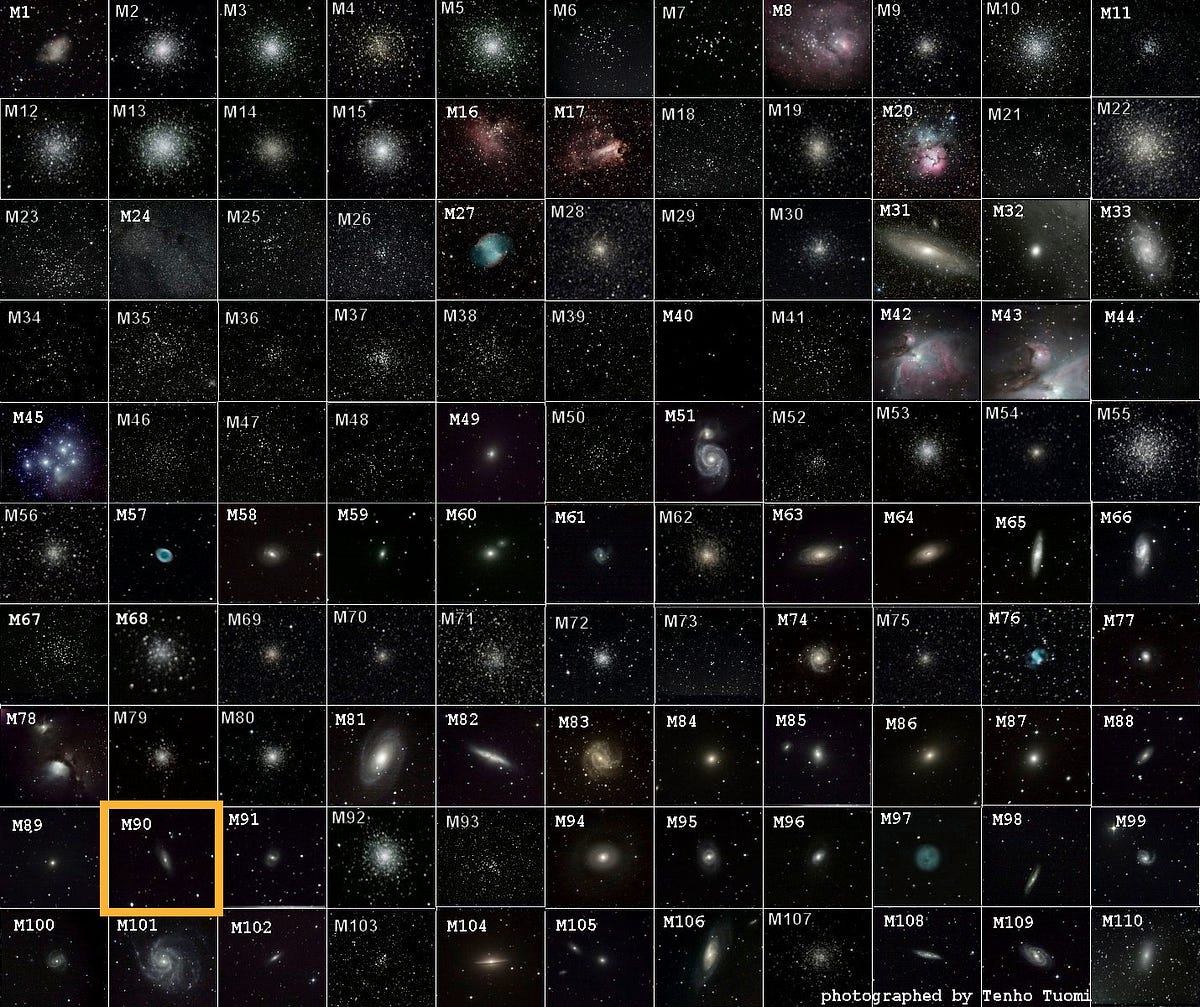

As you can see, this is a very dense region of space in terms of galaxies, and these are just the biggest, brightest ones visible to us. In reality, there are an estimated 2,000 galaxies in the Virgo Cluster, but Messier 90 is one of the brightest and largest of all the spirals, significantly brighter than our neighboring big sister: Andromeda. An original discovery by Messier himself in 1781, he described it as:

Nebula without star, in Virgo: its light is as faint as the preceding, No. 89.

But there’s no excuse for having a blasé attitude about this object in light of what we’ve discovered since!

Originally, Messier 90 was a source of controversy; it’s one of the rare galaxies with a blueshift, meaning it’s moving towards us. For a while, there was a contingent of astronomers who argued that it wasn’t a part of the Virgo Cluster at all, but was rather a foreground object, much closer than its presently-estimated distance of 59 million light-years. Instead, we now understand that on average the Virgo cluster recedes from us at a little over 1,000 km/s, but that the individual galaxies inside typically move relative to that number at up to 1,500 km/s, known as peculiar velocity.

Occasionally — such as in the case of M86 and this one as well — these factors conspire so that a giant galaxy appears to be moving towards us, but this is temporary; they’re quite bound inside the Virgo cluster and will reverse their direction within hundreds of millions of years from now.

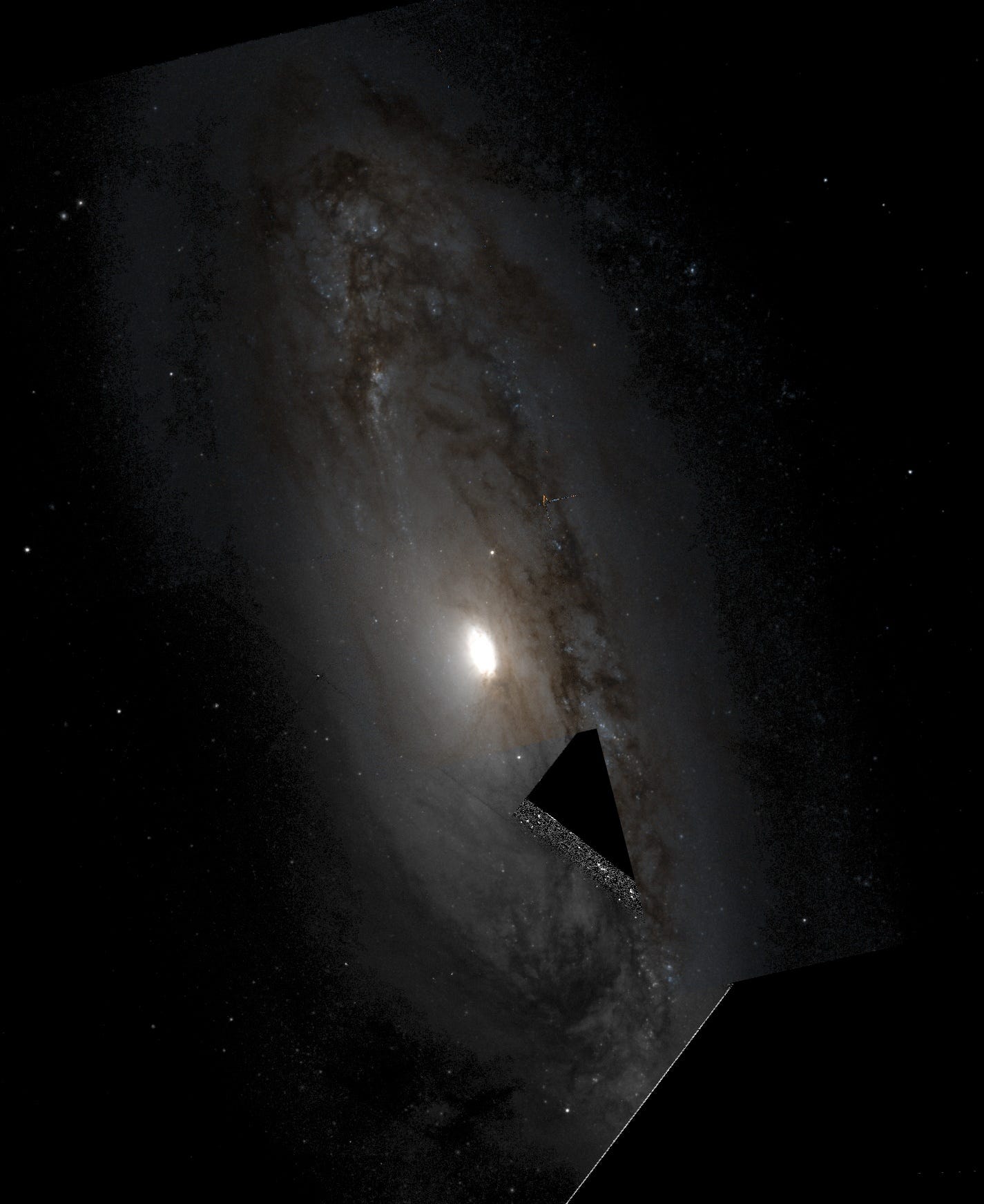

You’ll also notice that not only are there other galaxies nearby, but that there are large outstretched spiral arms that look distorted around this galaxy. These two phenomena are related; it appears to be gravitationally interacting with its neighboring smaller galaxy, IC 3583, which is disrupting the structure of the outer spiral arms. These tidal forces are most pronounced along the edges of the galaxy, where deviations in the orbits of stars shows up most prominently.

However, unlike most interacting galaxies, Messier 90 does not exhibit signs of intense star formation along its arms. In fact, it seems to be incredibly poor in gas for a spiral galaxy, and contains very few star-formation regions along its arms even relative to a quiet galaxy like our own!

Why could this be happening? Quite simply, when you take a normal galaxy and send it speeding at high velocity through the center of a dense cluster of galaxies, it’s going to be very sensitive to even sparse amounts of matter present in the intracluster medium. Over time, a phenomenon known as ram-pressure stripping has caused the vast majority of interstellar gas and dust to be entirely removed from this galaxy. But there’s one place — where gravity is strongest — that’s held on tightly to its gas: the center!

There are literally 50,000 of the most massive, bright blue O-and-B-class stars in the central region of this galaxy that have formed over no more than the past 6 million years. As a result, the center of the galaxy is now producing ‘superwinds’ due to a combination of the radiation pressure and from a heightened rate of supernovae that are blowing out even more of the central gas into the intracluster medium. Even though it’s conspicuous, very large and bright, it’s much lower in mass than we’d expect for a galaxy of this size, indicating just how much of this galaxy has been stripped away!

Even though there must have been many relatively recent supernovae in the center of this galaxy to explain the winds (and expected from the intense ultraviolet radiation coming from it), Messier 90 is one of the few galaxies in the catalogue that has never yet had a single supernova observed in it. It may be a highly unusual galaxy that’s fighting for its life and to maintain its spiral integrity, but — at least for this pass through the cluster’s center — it looks like it’s a survivor!

And that will wrap up today’s Messier Monday. Take a look back at any or all of our previous entries:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M4, A Cinco de Mayo Special: May 5, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M10, A Perfect Ten on the Celestial Equator: May 12, 2014

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M49, Virgo’s Brightest Galaxy: March 3, 2014

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M58, The Farthest Messier Object (for now): April 7, 2014

- M59, An Elliptical Rotating Wrongly: April 28, 2014

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M61, A Star-Forming Spiral: April 14, 2014

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M68, The Wrong-Way Globular Cluster: March 17, 2014

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M85, The Most Northern Member of the Virgo Cluster, February 10, 2014

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M87, The Biggest One of them All, March 31, 2014

- M88, A Perfectly Calm Spiral in a Gravitational Storm, March 24, 2014

- M90, The Better-You-Look, The Better-It-Gets Galaxy, May 19, 2014

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M98, A Spiral Sliver Headed Our Way, March 10, 2014

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M105, A Most Unusual Elliptical: April 21, 2014

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

And join us back here next week for another spectacular Messier Monday!

Enjoyed this? Leave a comment on the Starts With A Bang forum at Scienceblogs!