Messier Monday: Messier’s Final Galaxy, M110

The last object in the entire Messier Catalogue is faint, elusive, and the most common type of galaxy in the Universe!

Image credit: Adam Block / NOAO / AURA / NSF, via RC Optical Systems.

“The human mind is capable of excitement without the application of gross and violent stimulants; and he must have a very faint perception of its beauty and dignity who does not know this.” –William Wordsworth

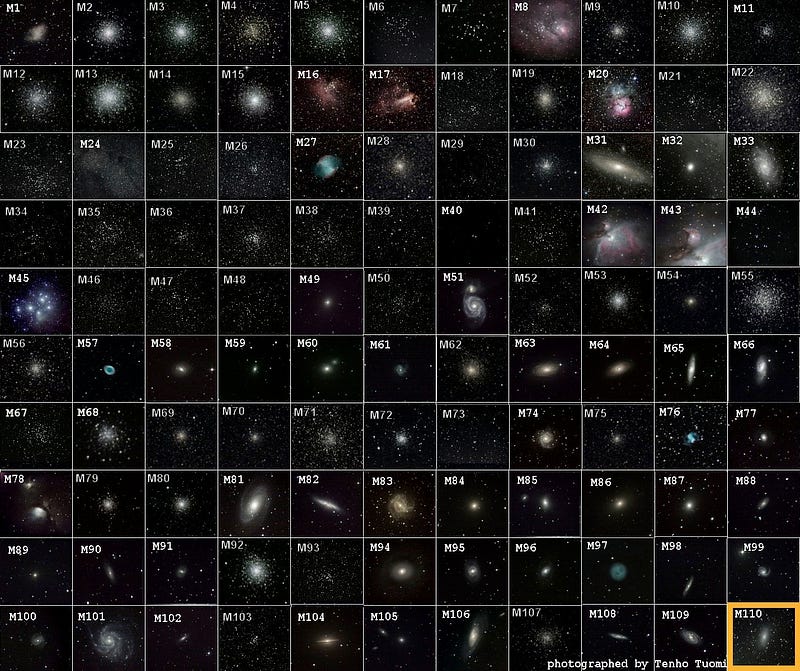

There are plenty of bright, extended objects in the night sky, clearly distinct from the stars and planets. While a few of them happen to be comets or asteroids within our own Solar System, the vast majority are star clusters, nebulae and galaxies ranging from a few hundred to many billions of light years away. The first large, accurate and verifiable catalogue of these deep sky objects was the Messier Catalogue, consisting of 110 objects. Although Messier himself didn’t know about our modern categories, it turns out that a whopping forty of these objects are galaxies, more than any other type.

Most of the galaxies that he found were nearby, bright giant galaxies: some spirals and some ellipticals, with the majority of them larger and more massive than our own Milky Way. But a few of these galaxies are much harder to find: smaller, fainter, lower in mass and much more compact. Although he never would have known it, they’re the most common type of galaxy in the entire Universe, and the very last object in his entire catalogue, Messier 110, is perhaps the best example of them.

Here’s how to find it in tonight’s sky.

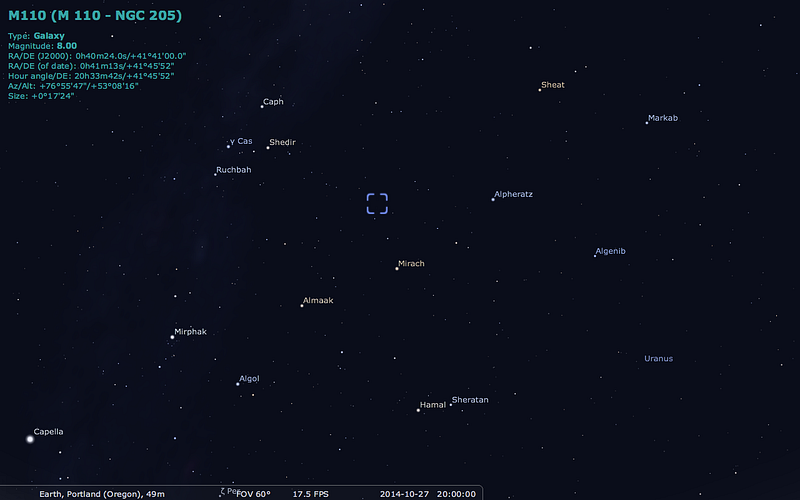

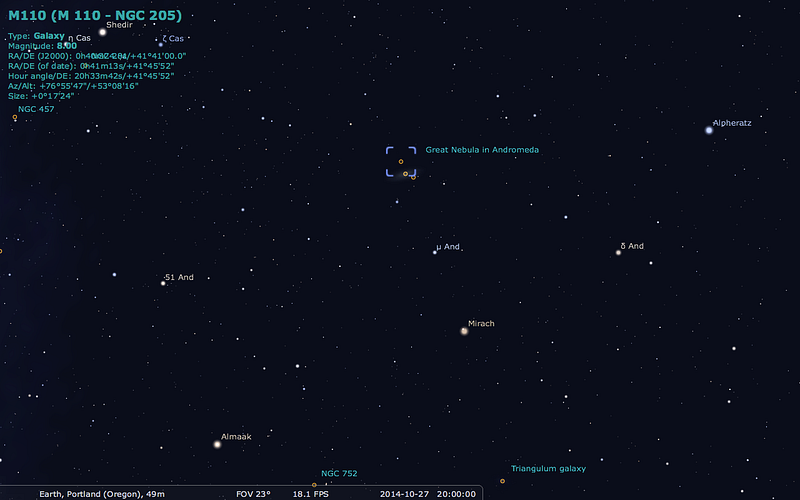

After sunset, the sky will darken, and then even moreso a hour or so later when the Moon sets. In the north, Polaris (the North Star) will be flanked, as it always is, by the Big Dipper on one side and by the great “W” of Cassiopeia on the other. And if you look beneath the bottom of the “W”, you’ll find a row of four bright stars: Mirphak, Almaak, Mirach and Alpheratz. Look to Mirach — β Andromedae — the third of these, to guide you towards Messier 110.

Directly “above” it, or back towards the “W”, you’ll find one star that stands out just a handful of degrees away: μ Andromedae, clearly visible to the naked eye even with the Moon out. About the same distance away, roughly along the same line, you’ll come to ν Andromedae, a magnitude dimmer but still not too difficult to find. And right above that star, you’ll come to the great nebula in Andromeda, M31, the Andromeda Galaxy.

Don’t stop there, though! Continue upwards a little further — on the opposite side from ν Andromedae — and you’ll find a much smaller fuzzy object, visible only through a telescope. That’s Messier 110. Recorded the night Charles Messier sketched the great nebula in 1773, he gave the account of its discovery in 1801:

On August 10, [1773,] I examined, under a very good sky, the beautiful nebula of the girdle of Andromeda, with my achromatic refractor, which I had made to magnify 68 times […] I saw that which C. Legentil discovered on October 29, 1749 [Messier 32]. I also saw a new, fainter one, placed north of the great [nebula], which was distant from it about 35′ in right ascension and 24′ in declination. It appeared to me amazing that this faint nebula has escaped the astronomers and myself, since the discovery of the great [nebula] by Simon Marius in 1612, because when observing the great [nebula], the small is located in the same field of the telescope. I will give a drawing of that remarkable nebula in the girdle of Andromeda, with the two small [nebulae] which accompany it.

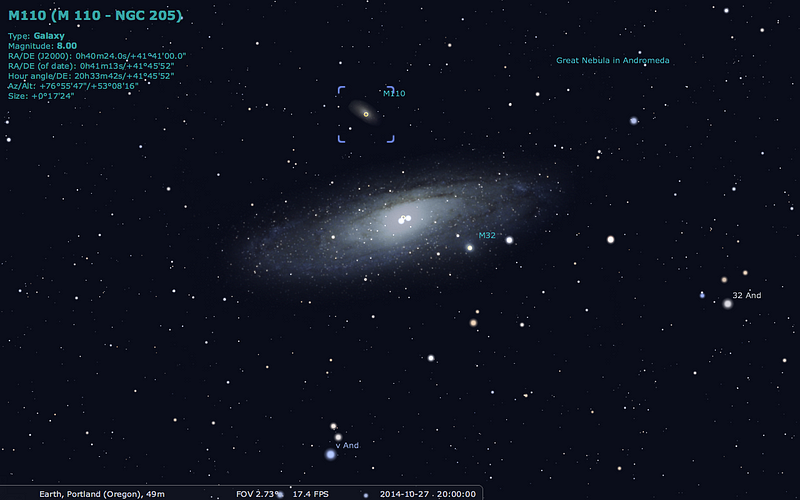

With modern equipment, it’s easy to spot with the unaided eyeball through a telescope.

And with a good amateur telescope and some quality astrophotography equipment, you can discover that it’s much more than an ellipsoidal fuzzball, but rather its own island Universe!

It wasn’t the final object discovered in the Messier catalogue, but the final one added, as that decision was only made in 1967. A good thing, too, because it not only totally belongs (having been discovered and catalogued by Messier), but it teaches us something new about the Universe that no other Messier object does.

As it turns out, Messier 110 is the only dwarf spheroidal galaxy in the entire Messier catalogue, and was most likely only discovered because of its proximity to its much larger neighbor. This is no coincidence, mind you, as this object is in fact a gravitationally bound satellite of its larger neighbor! At present, it’s located around 2,700,000 light-years from us, with an estimated distance of a few hundred thousand light-years from Messier 31.

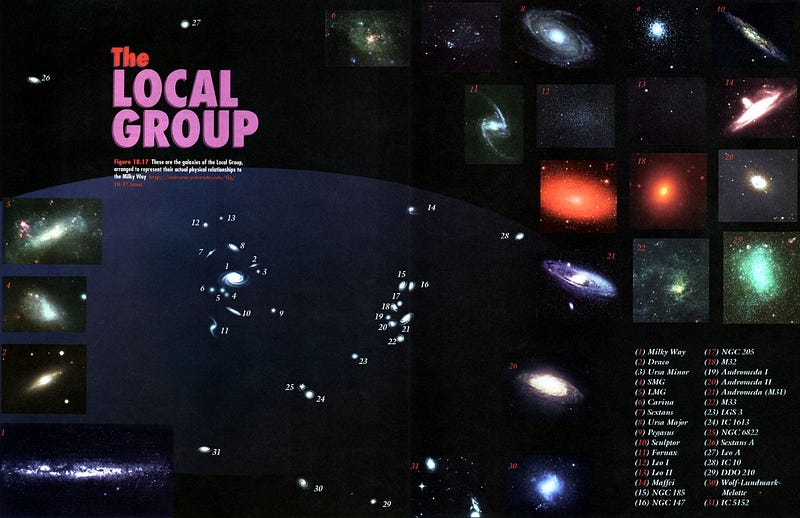

In fact, the discovery of this object was our first clue to the true nature of how galaxies cluster together: not only in groups of large spirals (like our Milky Way, M31 and M33) that can grow into ellipticals after major mergers, but full of smaller, irregular galaxies that eventually cluster around and merge with the larger galaxies themselves! At a later date, it was recognized that the Magellanic Clouds — not visible from Messier’s location far in the nouthern hemisphere — were satellites of our own Milky Way galaxy. At present we now know there to be not only the three large spiral galaxies in our local group, but some forty dwarf galaxies of various sizes and in various stages of their lives! Messier 110 (NGC 205) is just one of them that happens to be relatively easy to find.

Why is that? In addition to being both close to and well-separated from Andromeda, it’s actually on the larger side of these dwarf galaxies, containing an estimated four-to-fifteen billion solar masses of material, with over a billion stars inside!

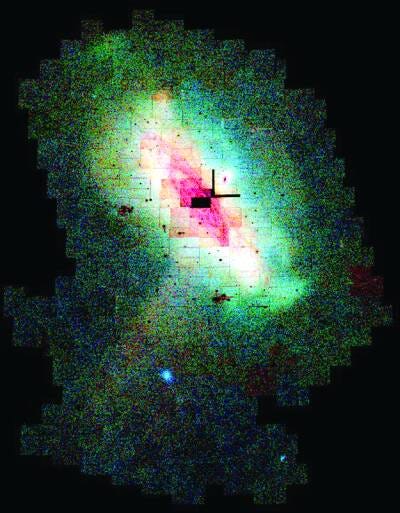

It’s also remarkable for another reason: most small, satellite galaxies have their interstellar gas stripped away by gravitational encounters with their larger neighbors. But Messier 110 still has a large amount of its gas intact, as evidenced by multiple populations of young, blue stars, evidence that it’s undergone star formation very recently. The youngest stars in there formed just 25 million years ago, with the formation most likely catalyzed by periodic encounters with the Andromeda galaxy!

It also has dust, which is visible due to its light-blocking effects in the visible, but which becomes transparent at infrared wavelengths.

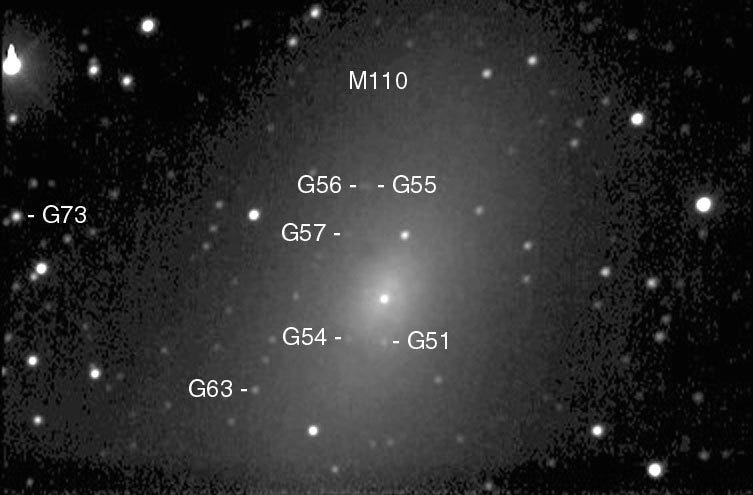

This galaxy is highly elliptical, and in a very rare occurrence for a galaxy this small, it has its own system of globular clusters, with eight identified so far.

It also is being clearly disrupted by its giant neighbor, as streams of gas are being pulled out of the galaxy, something we only discovered recently thanks to the Isaac Newton Telescope, but which can be verified with the right wavelengths in the optical as well!.

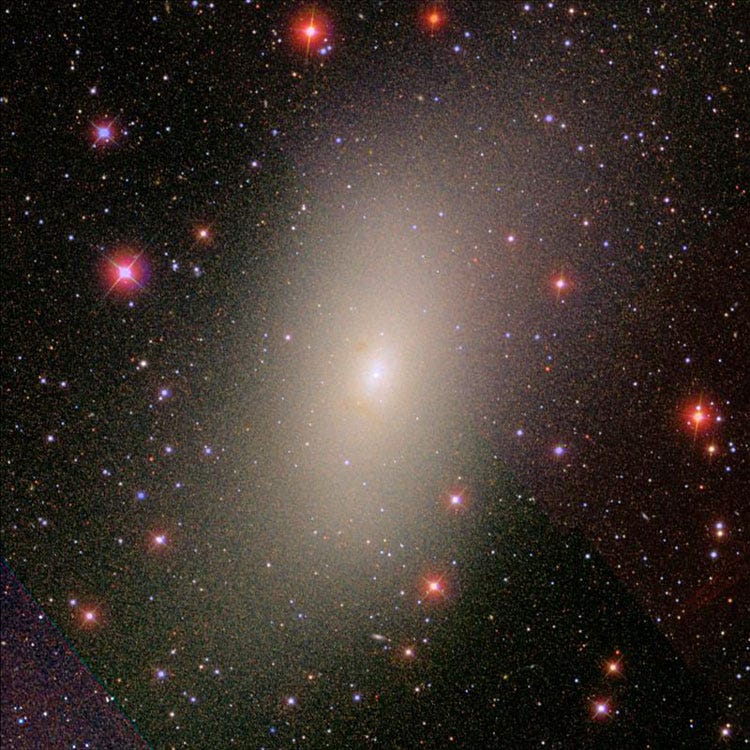

Finally, the most spectacular image available of this galaxy comes not from Hubble — even though the data exists — since it’s never been professionally processed. There’s a pretty good one from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey:

But even that’s not the best. Remember, this isn’t the brightest, biggest, or closest galaxy to us, but it is the most common type of galaxy in the Universe — some ten times as common as a spiral like us — and we should consider ourselves luck to have an example waiting for us at the end of the Messier catalogue. And the greatest tour through this galaxy comes courtesy of amateur astronomer extraordinaire Jim Misti, whose 32″ telescope captured the following spectacular image:

You can even see a distant background galaxy through this dwarf galaxy at the bottom of the image. And with that, we come to the final object and the final galaxy of the Messier catalogue. We’ve only got four objects left, so enjoy your tour through the other 105 that we’ve covered here:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M4, A Cinco de Mayo Special: May 5, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M6, The Butterfly Cluster: August 18, 2014

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M9, A Globular from the Galactic Center: July 7, 2014

- M10, A Perfect Ten on the Celestial Equator: May 12, 2014

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M14, The Overlooked Globular: June 9, 2014

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M16, The Eagle Nebula: October 20, 2014

- M17, The Omega Nebula: October 13, 2014

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M19, The Flattened Fake-out Globular: August 25, 2014

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M22, The Brightest Messier Globular: October 6, 2014

- M23, A Cluster That Stands Out From The Galaxy: July 14, 2014

- M24, The Most Curious Object of All: August 4, 2014

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M27, The Dumbbell Nebula: June 23, 2014

- M28, The Teapot-Dome Cluster: September 8, 2014

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M49, Virgo’s Brightest Galaxy: March 3, 2014

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M54, The First Extragalactic Globular: September 22, 2014

- M55, The Most Elusive Globular Cluster: September 29, 2014

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M58, The Farthest Messier Object (for now): April 7, 2014

- M59, An Elliptical Rotating Wrongly: April 28, 2014

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M61, A Star-Forming Spiral: April 14, 2014

- M62, The Galaxy’s First Globular With A Black Hole: August 11, 2014

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M68, The Wrong-Way Globular Cluster: March 17, 2014

- M69, A Titan in a Teapot: September 1, 2014

- M70, A Miniature Marvel: September 15, 2014

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M80, A Southern Sky Surprise: June 30, 2014

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M84, The Galaxy at the Head-of-the-Chain, May 26, 2014

- M85, The Most Northern Member of the Virgo Cluster, February 10, 2014

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M87, The Biggest One of them All, March 31, 2014

- M88, A Perfectly Calm Spiral in a Gravitational Storm, March 24, 2014

- M89, The Most Perfect Elliptical, July 21, 2014

- M90, The Better-You-Look, The Better-It-Gets Galaxy, May 19, 2014

- M91, A Spectacular Solstice Spiral, June 16, 2014

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M98, A Spiral Sliver Headed Our Way, March 10, 2014

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M100, Virgo’s Final Galaxy, July 28, 2014

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M105, A Most Unusual Elliptical: April 21, 2014

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M107, The Globular that Almost Didn’t Make it: June 2, 2014

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

- M110, Messier’s Final Galaxy: October 27, 2014

Come back next week for a view of a brilliant cluster, as we enter the final month of Messier Monday here on Starts With A Bang!

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs!