Messier Monday: A Most Unusual Elliptical, M105

“Red and dead” might describe the stars in most ellipticals, but this nearby galaxy tells a different story.

“The line that describes the beautiful is elliptical. It has simplicity and constant change. It cannot be described by a compass, and it changes direction at every one of its points.” –Rudolf Arnheim

There are many giant elliptical galaxies in the Universe: the results of long-ago mergers of many smaller galaxies that formed them. Our own local group will someday become one as well, and the Virgo Cluster — the nearest ultra-rich grouping of over a thousand galaxies — contains a great many of them. But among the Messier objects, there’s only one giant elliptical that isn’t in the Virgo cluster, and that’s the subject of today’s Messier Monday.

In general, galaxies are most densely grouped together in extremely large clusters, with smaller groups on the outskirts, roughly connected by filaments to the largest structures. About halfway from our local group to Virgo lies a couple of smaller groups in the constellation of Leo, and that’s where today’s remarkable object — Messier 105 — lives.

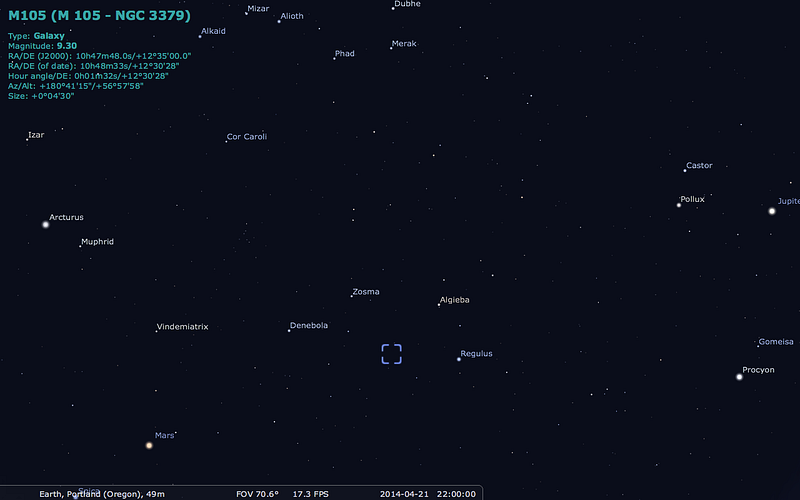

Here’s how to find it for yourself.

The constellation of Leo has some bright, prominent stars, and you can find it simply by locating the Big Dipper, orienting yourself so that the “cup” of the dipper is full, and looking “beneath” the dipper itself. The brightest star in that region of sky is Regulus, the brightest star in Leo. You’ll easily be able to see a number of others, including Denebola, the second brightest.

And if you look midway between those two — Denebola and Regulus — you’ll be well on your way to Messier 105.

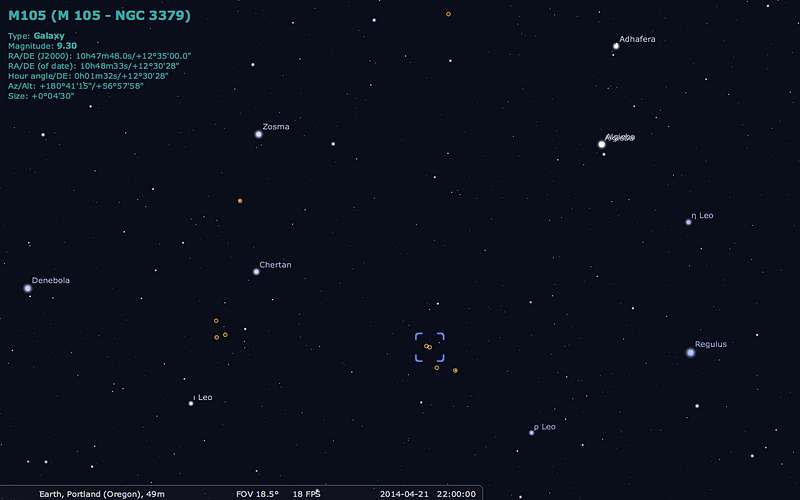

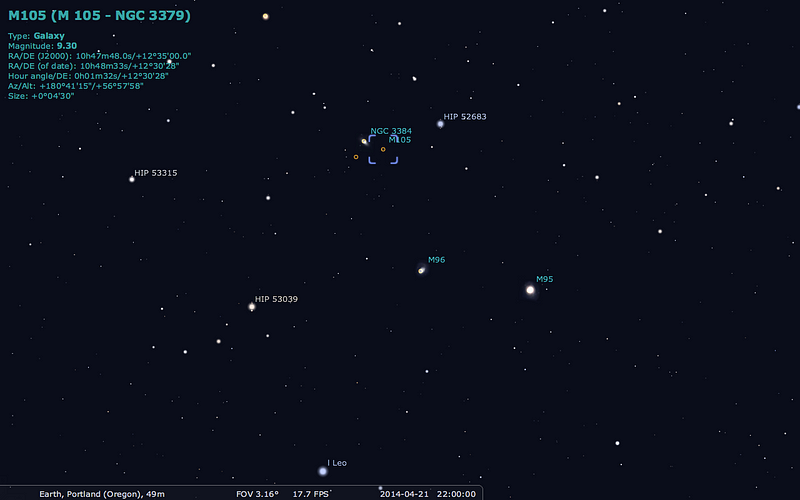

This galaxy also lies midway between two other prominent stars in Leo: Chertan and ρ Leonis. There is, in fact, a sizeable group of galaxies in this region of space: the M96 Group, containing maybe three times as many large galaxies as our own local group. And there’s one particular star shown below — HIP 52683 — that’s just invisible to the naked eye. But if you can find it in binoculars or a telescope, Messier 105 will be unmistakeable.

Messier 105 was a late addition to this catalogue, discovered by Messier’s assistant Pierre Méchain, and recorded as this:

[T]wo nebulous stars, which I have discovered in the Leo [M95 and M96]; I find nothing to change for my positions which I have established by comparing these nebulae to Regulus; but there is also a third one to the north; it is a bit more beautiful than the 2 others; I have discovered it on March 24, 1781, 4 or 5 days after the other two.

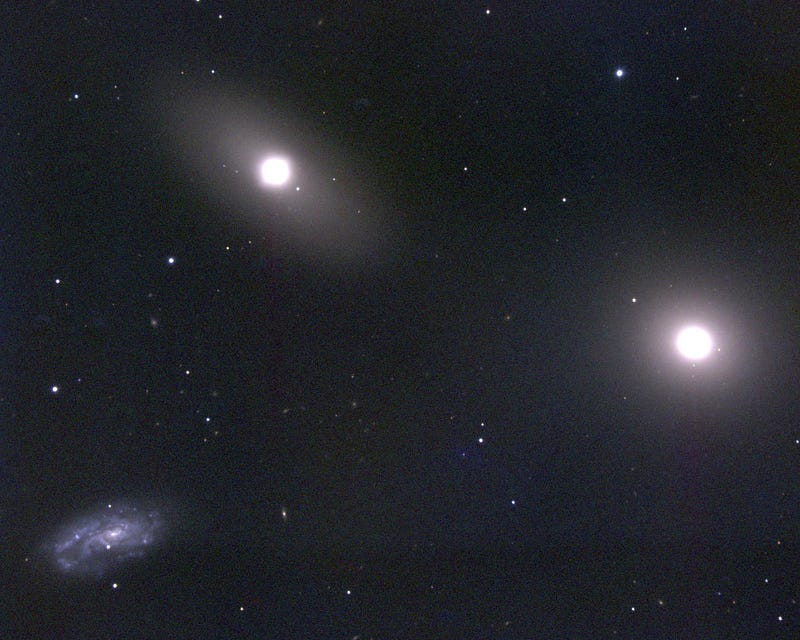

Through a small telescope, it might look something like this.

Pretty hard to see anything, isn’t it? This wide-field view has the galaxies M95 and M96 along the right side, with Messier 105 as the slightly “fuzzy star” at the 6 o’clock position. The star HIP 52683 we talked about earlier is just below and to the left of center, and M105 is the “fuzzy” star closest to it.

Let’s take a closer look to find out more about it.

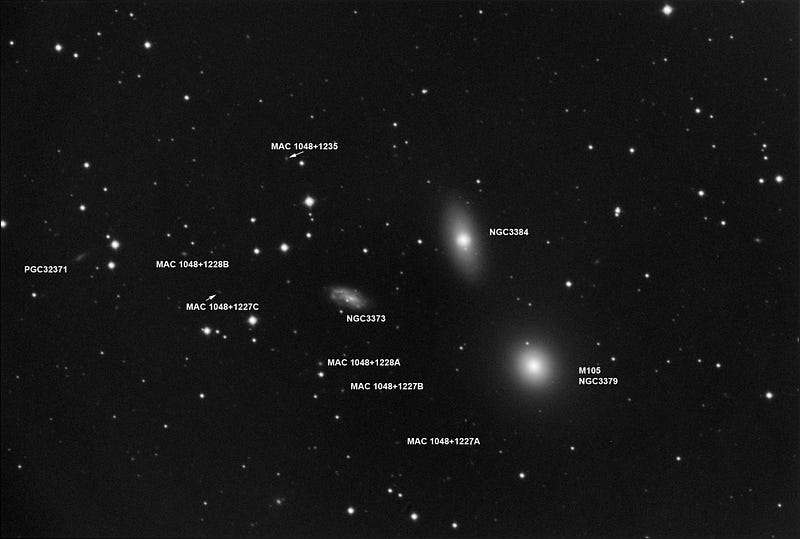

Unlike the other two Messier objects in this substantial group, Messier 105 is located very nearby to two other galaxies: NGC 3384 and NGC 3389, the former of which is another giant elliptical galaxy. Along with Messier 105, these galaxies must have undergone a series of major mergers long ago, forming stars in an intense burst and losing the vast majority of the gas capable of forming new stars.

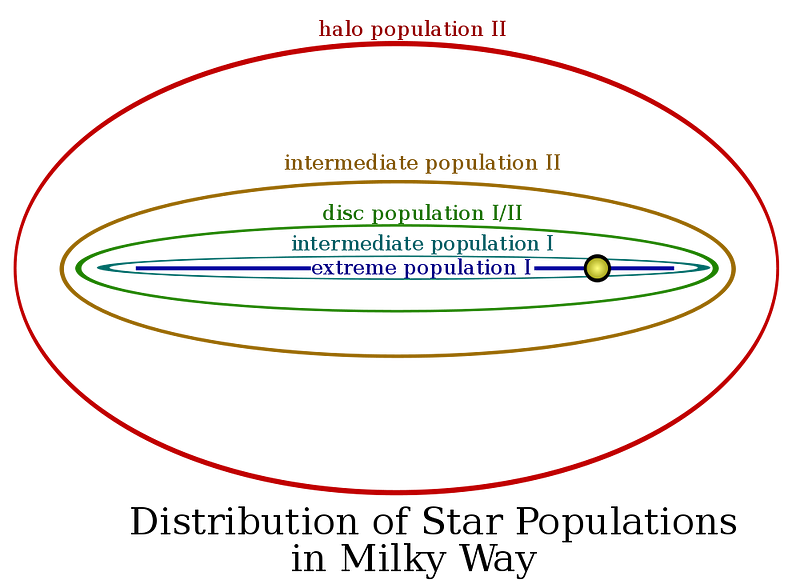

Over 80% of the stars in these ellipticals are classified as Population II, meaning that they were formed over a billion years ago, and are much poorer in elements heavier than helium than our Sun is. If you look at galaxies like ours in general, we find that metal-rich stars (like ours) are found concentrated in the plane of the disk, and that the metal-poor ones are found in the halo.

Finding so many metal-poor stars in this elliptical galaxy is suggestive that it’s been an elliptical for a long time already!

At 32 million light-years distant, these galaxies are only about halfway to the Virgo Cluster from where we are, are huge, with an estimated mass of about a hundred billion Suns in M105 alone. That’s on the same order as the Milky Way, mind you, but if we look in the X-ray, we find something very different from our Milky Way.

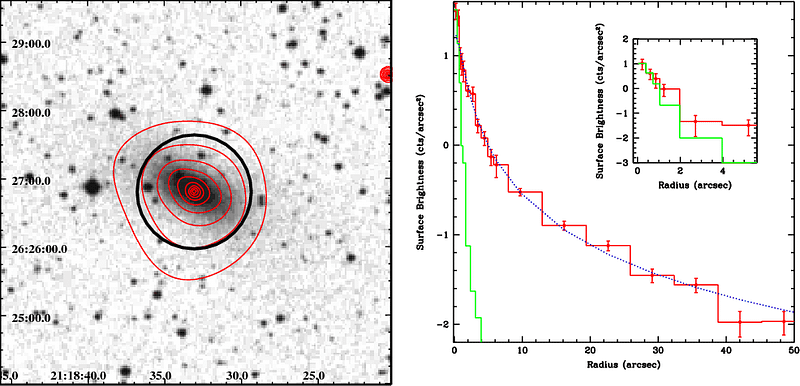

One of the telltale signs of giant elliptical galaxies seems to be a powerful X-ray source at the center, indicative of a much larger black hole than the supermassive one at our galaxy’s center. Whereas ours weighs in at about 4 million times the mass of our Sun, M105’s black hole is about 200 million times the Sun’s mass!

On the other hand, most elliptical galaxies consist of practically no new, blue stars and are devoid of neutral hydrogen gas, another stark difference from our Milky Way.

It may be very difficult to see from most optical images, but it turns out that this elliptical galaxy — one of the closest typical giant ellipticals — may be turning that piece of information on its head! You see, even though it does have lots of old, red stars, and very little in the way of hot, new young stars, there’s actually a huge halo of neutral gas centered on this galaxy!

Whereas our Milky Way has a radius of about 50,000 light-years, the halo of neutral gas surrounding M105 extends for about 650,000 light-years, an incredible distance! Despite being a gas-poor galaxy, there are still more than a billion Suns worth of neutral gas surrounding it, a very large amount.

And you might think that it’s rare to have three galaxies grouped together like this, but if we take more detailed observations, we actually find that it isn’t just these three, but there are a great deal more if we include smaller, fainter satellite galaxies of these major ones!

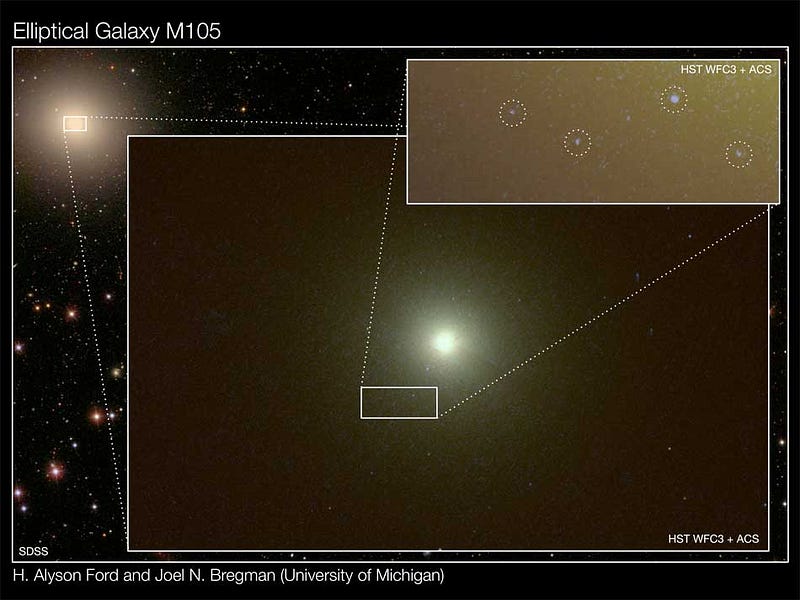

Yet perhaps most remarkably, we’ve very recently learned that this galaxy’s gas — much like the neutral gas in most galaxies — is actually collapsing to form not only new stars, but new star clusters as well!

As Alyson Ford and Joel Bregman discovered using ultraviolet observations of this galaxy with the Hubble Space Telescope:

We were confused by some of the colors of objects in our images until we realized that they must be star clusters, so most of the star formation happens in associations.

[…]

This is not just a burst of star formation but a continuous process.

And finally, there are a large number of Hubble observations of M105, but my favorite is a long, 39000-second exposure (in two different filter bands), that actually shows off what’s behind Messier 105! Take an unbelievable look:

If this reminds you of one of the Hubble Deep Fields, it should! There are literally hundreds of background galaxies visible in the image above, further showing that galaxies are literally everywhere in the Universe, even behind some of the brightest galaxies in our local neighborhood!

So with that, we’ll bring today’s Messier Monday to a close. Take a look back at all our previous Messier Mondays here!

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M49, Virgo’s Brightest Galaxy: March 3, 2014

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M58, The Farthest Messier Object (for now): April 7, 2014

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M61, A Star-Forming Spiral: April 14, 2014

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M68, The Wrong-Way Globular Cluster: March 17, 2014

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M85, The Most Northern Member of the Virgo Cluster, February 10, 2014

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M87, The Biggest One of them All, March 31, 2014

- M88, A Perfectly Calm Spiral in a Gravitational Storm, March 24, 2014

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M98, A Spiral Sliver Headed Our Way, March 10, 2014

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M105, A Most Unusual Elliptical: April 21, 2014

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

I hope you enjoyed this remarkable object and it’s story, and don’t forget to come back next week for another deep-sky wonder, only here, for another Messier Monday!

Weigh in and have your say at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs!