Now that New Horizons has flown by the Plutonian system, can it be considered a planet after all?

“Words are the source of misunderstandings.” –Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

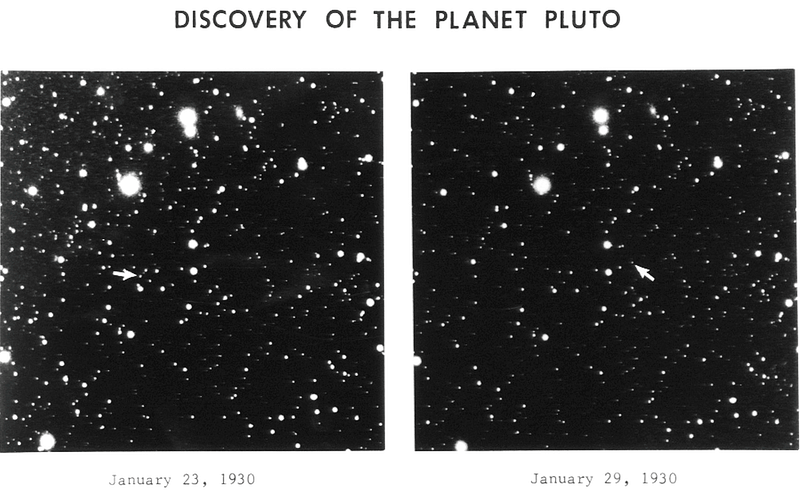

Back in 1930, Clyde Tombaugh was using a blink comparator, where the same region of sky would be photographed on two different nights. While the stars and nebulae would appear in the same exact position, since their motions are far too small to detect at such great distances, objects like comets, asteroids or planets would shift from night-to-night. In the early part of that year, the course of astronomical history would change forever.

For the first time, a large, non-cometary body orbiting our Sun out beyond Neptune had been discovered. And for 48 years, Pluto reigned alone as the only such object with that status. Finally, in the late 1970s, a second object joined it: Pluto’s giant moon, Charon. Again, for over a decade, the Plutonian system was the only one out there.

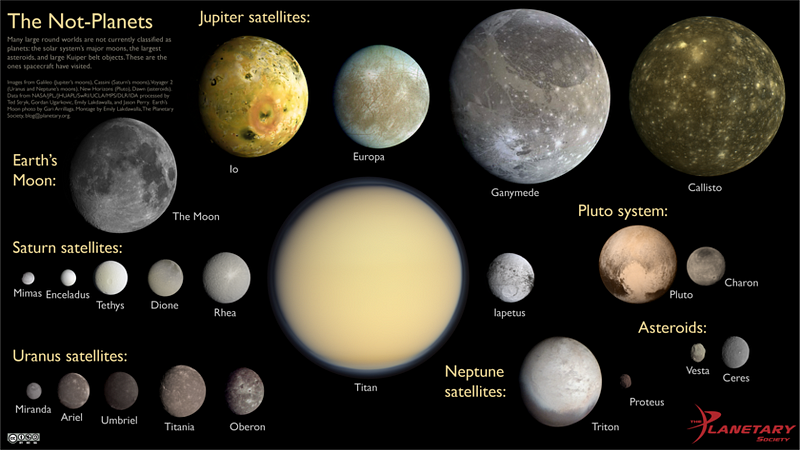

And yet, Pluto was different from everything else. It was far smaller than all the other planets (even Mercury or Mars), much smaller than many of the Solar System’s moons, interior to the orbit of Neptune (and almost Uranus) at time, and highly inclined to the ecliptic, unlike any of the other worlds.

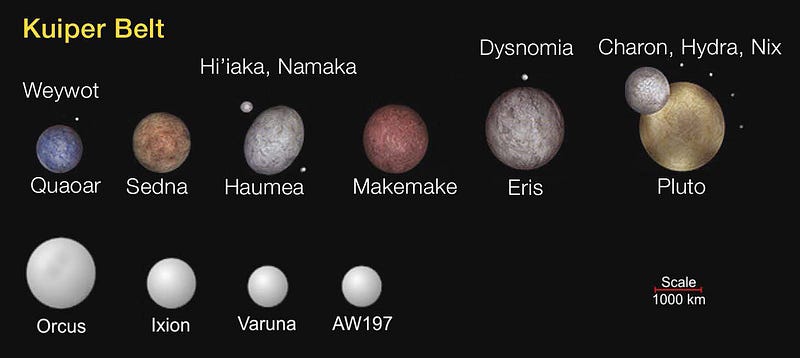

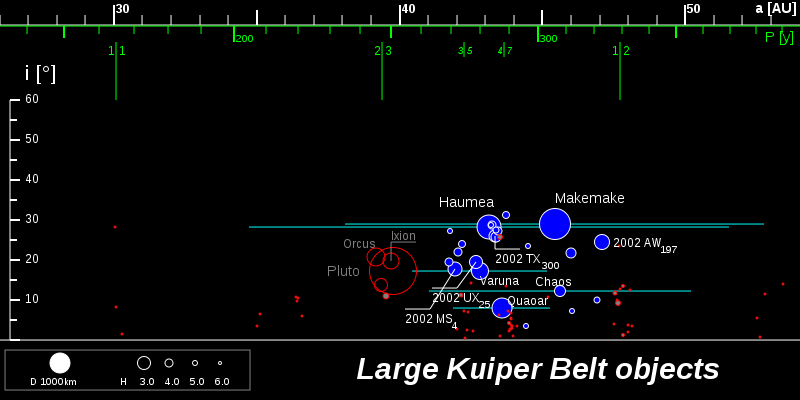

Finally, in the 1990s (starting in 1992), we discovered other objects out beyond the orbit of Neptune. Not only was Pluto (and its giant moon) out there, along with a large fraction of the known periodic comets, but many other objects as well, such as Eris, Makemake, Quaoar and others.

Clearly, Pluto belonged much more closely to this class of objects than to the other planets of the Solar System. And just as previously discovered “planets” from the 1800s — Ceres, Pallas, Vesta, Juno and others — were demoted from planetary status when we realized that the asteroid belt was its own entity, Pluto’s status as a planet was not to last forever.

In 2006, quite controversially, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) officially defined a planet for the first time, stating that something had to meet three conditions:

- being in hydrostatic equilibrium (i.e., pulled into a round or spheroidal shape by its own gravity),

- not orbit another, more massive body (i.e., not be a moon), and

- to clear its orbit, so that it was the gravitationally dominant body at its distance from its star.

Just like that, Pluto was no longer a planet. And yet, it was still an object of tremendous interest and importance. So rather than relying on ground-based images or even Hubble images, we decided to go.

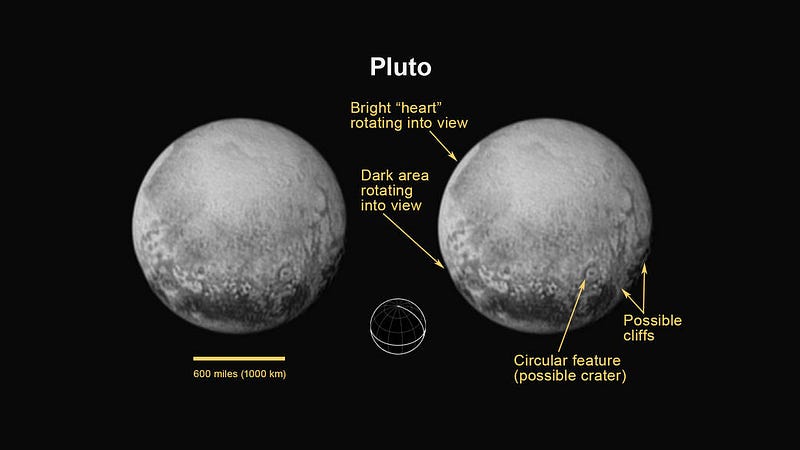

From 1930 until July 14, today, 2015, this video (above) showcases just how much better our pictures of Pluto have gotten since we left Earth and traveled to it. While the data transfer back is incredibly slow — not only does it take over four hours for the light to travel, but the data rate is terribly slow at just 1/8th of a kilobyte per second at such a great distance — we now have unprecedented views and data on Pluto and its neighboring worlds. We’ve discovered surface geology, incredible features, colors and atmospheric properties.

At last, Pluto is no longer a “dot” in the sky, but its own world with its own unique cosmic story.

The fly-by today was just the beginning: over the next sixteen months, data will pour in, telling us all sorts of information about Pluto’s surface, a variety of features including the white “heart”, the dark polar patches, the craters, cliffs and “mushrooms,” and a whole host of things we may not even notice today.

The possibilities are tremendous:

- Frozen water, methane, dry ice or even solid nitrogen (and you thought liquid nitrogen was cold) on the surface,

- A chance of weather and even snow,

- Active surface geology, including “black smokers” welling up from inside Pluto’s core,

- Additional moons, with the capability to detect ones just a single meter in size,

and so much more. Already, the discoveries are pouring in.

We know the exact size of Pluto, confirming that it’s larger than we thought, but not nearly as large as we once thought, decades ago.

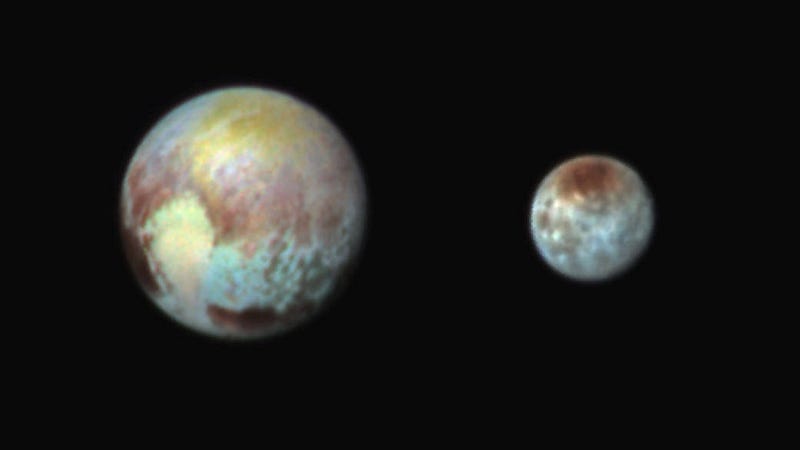

We learned there are dark spots on Charon, a wholesale surprise. Moons that small ought to be much more uniform, perhaps evidence that extreme tidal forces (or a violent past) has shaped Pluto’s largest moon.

A reddish color to the world overall, whose elemental composition will soon be revealed by New Horizons.

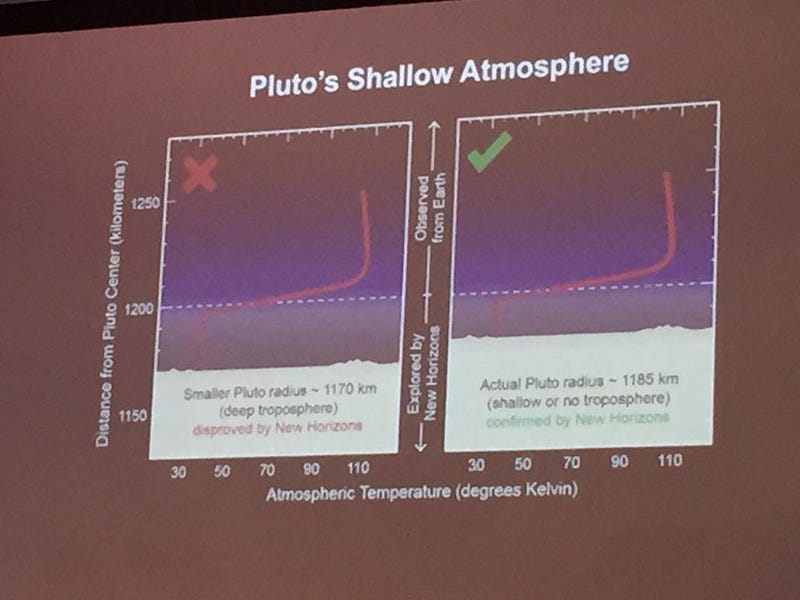

And we learned that Pluto does have an atmosphere, but that the lower atmosphere (the troposphere) is much thinner than we once suspected, or possibly even non-existent!

Last year, I argued that there are only eight planets in our Solar System, and that there don’t deserve to be any more than that.

But today, as we pass by Pluto and await the first science results, I’m not so sure. You see, Pluto is only the very first (and fittingly, Charon is the second) large Kuiper Belt Object to be studied so well, and studied up close at that.

But the large Kuiper Belt objects — the ones that at least meet the first of the I.A.U.’s planetary criteria — not only exist, but there are probably hundreds of them in our Solar System alone. In other words, for everything we call a planet, there are dozens of Pluto-like worlds out there.

And as we’re just starting to discover, for every planet we have in our Solar System, there are between tens to hundreds of thousands of planets without parent stars in the galaxy: rogue planets.

Now, here’s the thing that gets me and makes me think: if Pluto weren’t in our Solar System, we would have no problem calling it a “rogue planet.”

So why do we stop calling it a planet because it’s in our Solar System? Perhaps we need a better word that encompasses all the artificial categories we created. Something that includes rocky planets, large moons, gas giants, dwarf planets, rogue planets, large Kuiper belt objects, large asteroids, and so on.

Why don’t we just call them what they are: worlds.

These worlds tell the history of how everything in the Universe forms. They tell the elemental and chemical history of everything in our galaxy; they hold the secrets of the origin of the complex molecules, organics and life within them. Pluto and the other Kuiper belt objects, in particular, may hold the keys to understanding where the water on our planet or the nitrogen in our atmosphere came from.

And thanks to the New Horizons mission, we’re about to find these secrets out. In a very meaningful way, including Pluto back in the picture of our Solar System’s planets may be more honest — in terms of understanding what’s really important when it comes to a planetary system — than leaving it out.

I’ll be talking about New Horizons’ historic flyby today live on Portland’s KGW NewsChannel 8 at 7 PM (Pacific) tonight, with a permanent video embed to follow below.

While currently, that large feature seen on Pluto (at the lower right, above) has been dubbed a “heart” by many, I have a suspicion it’s a lot more. Alan Stern (a.k.a., the guy who killed Pluto and also the principle investigator) thinks it might be snowfall, and a transient feature. Others think it’s a permanent part of the surface geology.

Me? I think if you add ears, eyes and a nose, you’ll get your answer.

It may not be a planet, but Pluto is definitely a world unto itself.

Leave your comments at our forum, and support Starts With A Bang on Patreon!