One of cosmic inflation’s cofounders came out against it, calling it not even science. But it is… and so much more.

“There’s no obvious reason to assume that the very same rare properties that allow for our existence would also provide the best overall setting to make discoveries about the world around us. We don’t think this is merely coincidental.” –Guillermo Gonzalez

In order to be considered a scientific theory, there are three things your idea needs to do. First off, you have to reproduce all of the successes of the prior, leading theory. Second, you need to explain a new phenomenon that isn’t presently explained by the theory you’re seeking to replace. And third, you need to make a new prediction that you can then go out and test: where your new idea predicts something entirely different or novel from the pre-existing theory. Do that, and you’re science. Do it successfully, and you’re bound to become the new, leading scientific theory in your area. Many prominent physicists have recently come out against inflation, with some claiming that it isn’t even science. But the facts say otherwise. Not only is inflation science, it’s now the leading scientific theory about where our Universe comes from.

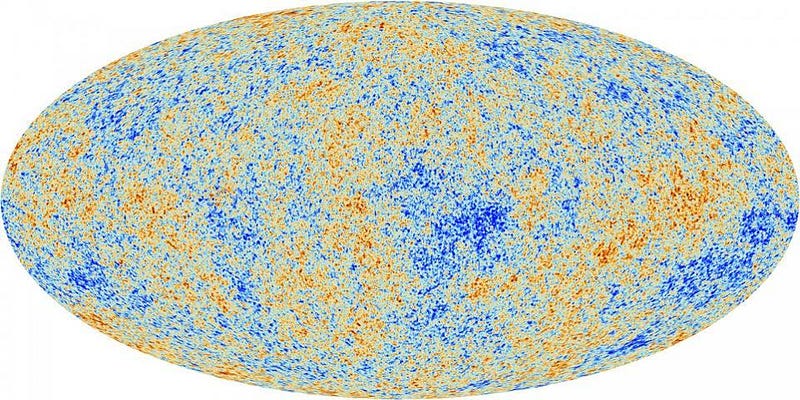

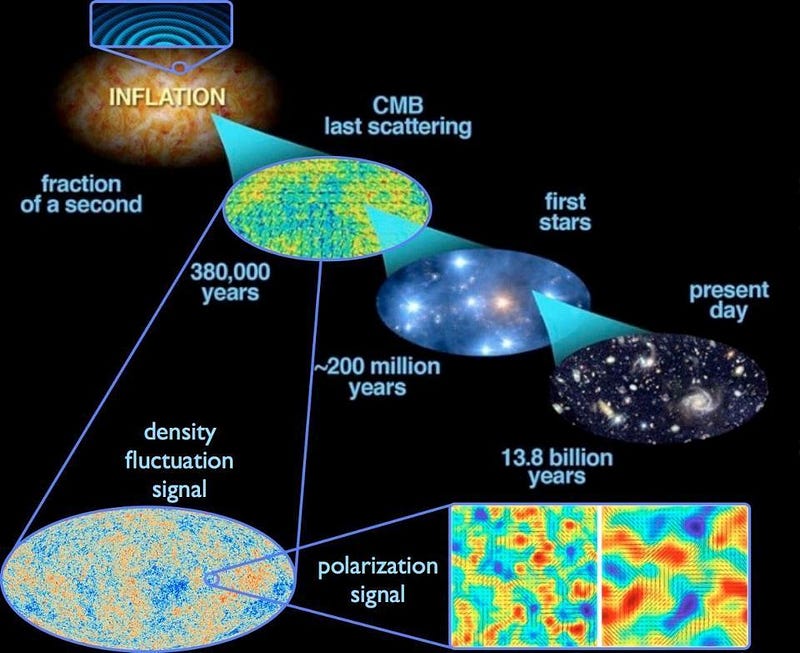

The Big Bang was first confirmed in the 1960s, with the observation of the Cosmic Microwave Background. Since that first detection of the leftover glow, predicted from an early, hot, dense state, we’ve been able to validate and confirm the Big Bang’s predictions in a number of important ways. The large-scale structure of the Universe is consistent with having formed from a nearly-uniform past state, under the influence of gravity over billions of years. The Hubble expansion and the temperature in the distant past is consistent with an expanding, cooling Universe filled with matter and energy of various types. The abundances of hydrogen, helium, lithium, and their various isotopes matches the predictions from an early, hot, dense state. And the blackbody spectrum of the Big Bang’s leftover glow matches our observations precisely.

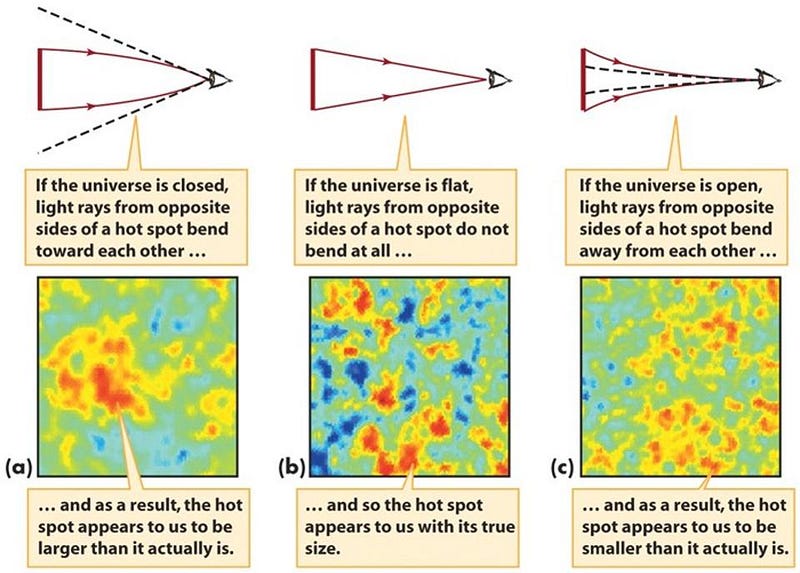

But there are a number of things that we observe that the Big Bang doesn’t explain. The fact that the Universe is the same exact temperature in all directions, to better than 99.99%, is an observational fact without a theoretical cause. The fact that the Universe, in all directions, appears to be spatially flat (rather than positively or negatively curved), is another true fact without an explanation. And the fact that there are no leftover high-energy relics, like magnetic monopoles, is a curiosity that we wouldn’t expect if the Universe began from an arbitrarily hot, dense state.

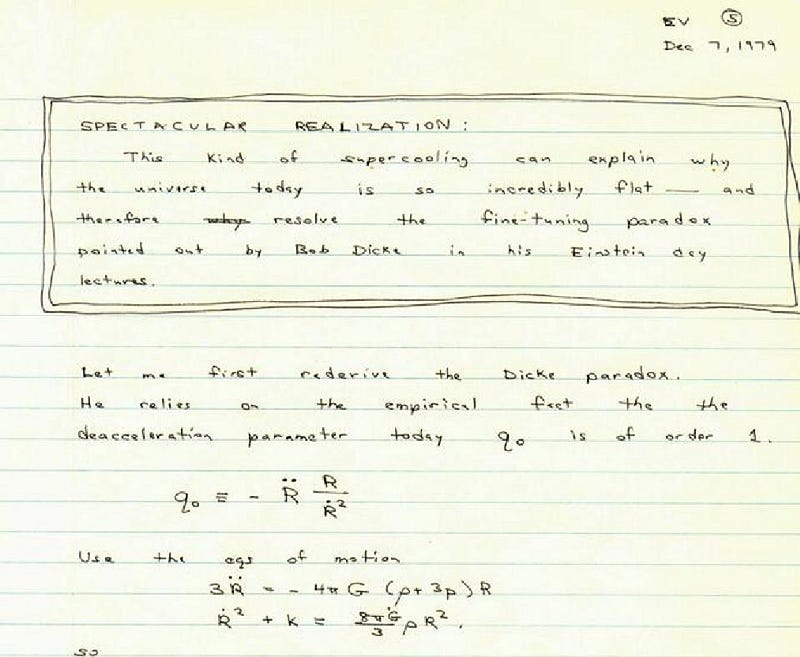

In other words, the implication is that despite all of the Big Bang’s successes, it doesn’t explain everything about the origin of the Universe. Either we can look at these unexplained phenomena and conjecture, “maybe the Universe was simply born this way,” or we can look for an explanation that meets our requirements for a scientific theory. That’s exactly what Alan Guth did in 1979, when he first stumbled upon the idea of cosmological inflation.

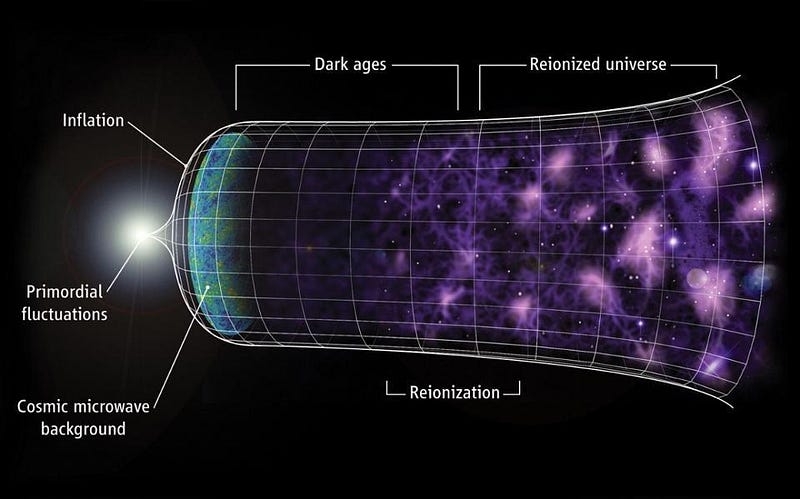

The big idea of cosmic inflation was that the matter-and-radiation-filled Universe, the one that has been expanding and cooling for billions of years, arose from a very different state that existed prior to what we know as our observable Universe. Instead of being filled with matter-and-radiation, space was full of vacuum energy, which caused it to expand not just rapidly, but exponentially, meaning the expansion rate doesn’t fall with time as long as inflation goes on. It’s only when inflation comes to an end that this vacuum energy gets converted into matter, antimatter, and radiation, and the hot Big Bang results.

It was generally recognized that inflation, if true, would solve those three puzzles that the Big Bang could only posit as initial conditions: the horizon (temperature), flatness (curvature), and monopole (lack-of-relics) problems. In the early-to-mid 1980s, lots of work went into meeting that first criteria: reproducing the successes of the Big Bang. The key was to arrive at an isotropic, homogeneous Universe with conditions that matched what we observed.

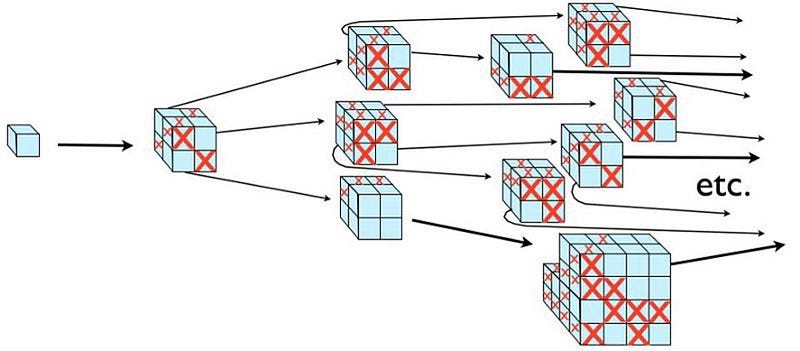

After a few years, we had two generic classes of models that worked:

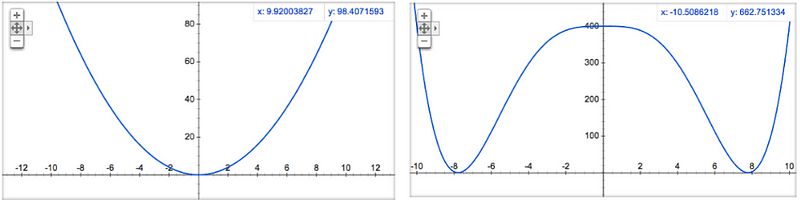

- “New inflation” models, where vacuum energy starts off at the top of a hill and rolls down it, with inflation ending when the ball rolls into the valley, and

- “Chaotic inflation” models, where vacuum energy starts out high on a parabola-like potential, rolling into the valley to end inflation.

Both of these classes of models reproduced the successes of the Big Bang, but also made a number of similar, quite generic predictions for the observable Universe. They were as follows:

- The Universe should be nearly perfectly flat. Yes, the flatness problem was one of the original motivations for it, but at the time, we had very weak constraints. 100% of the Universe could be in matter and 0% in curvature; 5% could be matter and 95% could be curvature, or anywhere in between. Inflation, quite generically, predicted that 100% needed to be “matter plus whatever else,” but curvature should be between 0.01% and 0.0001%. This prediction has been validated by our ΛCDM model, where 5% is matter, 27% is dark matter and 68% is dark energy; curvature is constrained to be 0.25% or less. As observations continue to improve, we may, in fact, someday be able to measure the non-zero curvature predicted by inflation.

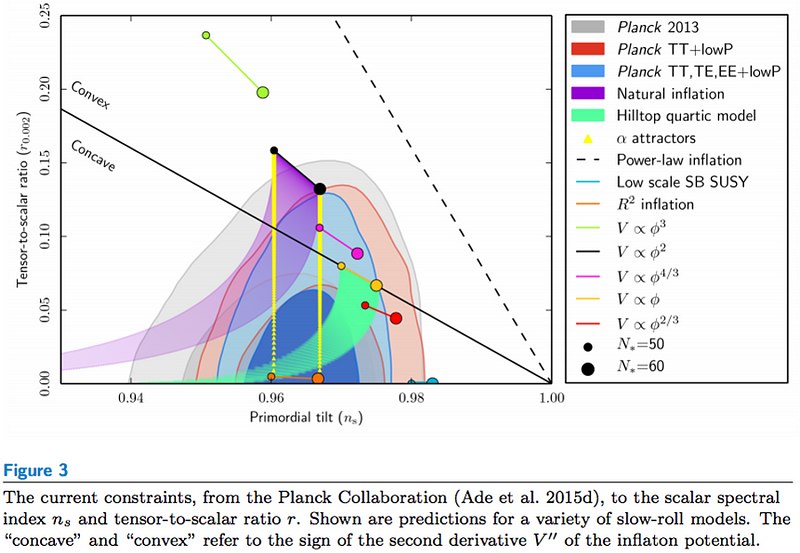

- There should be an almost scale-invariant spectrum of fluctuations. If quantum physics is real, then the Universe should have experienced quantum fluctuations even during inflation. These fluctuations should be stretched, exponentially, across the Universe. When inflation ends, these fluctuations should get turned into matter and radiation, giving rise to overdense and underdense regions that grow into stars and galaxies, or great cosmic voids. Because of how inflation proceeds in the final stages, the fluctuations should be slightly greater on either small scales or large scales, depending on the model of inflation, which means there should be a slight departure from perfect scale invariance. If scale invariance were exact, a parameter we call n_s would equal 1; n_s is observed to be 0.96, and wasn’t measured until WMAP in the 2000s.

- There should be fluctuations on scales larger than light could have traveled since the Big Bang. This is another consequence of inflation, but there’s no way to get a coherent set of fluctuations on large scales like this without something stretching them across cosmic distances. The fact that we see these fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background and in the large-scale structure of the Universe — and didn’t know about them until the COBE and WMAP satellites in the 1990s and 2000s — further validates inflation.

- These quantum fluctuations, which translate into density fluctuations, should be adiabatic. Fluctuations could have come in different types: adiabatic, isocurvature, or a mixture of the two. Inflation predicted that these fluctuations should have been 100% adiabatic, which should leave unique signatures in both the cosmic microwave background and the Universe’s large-scale structure. Observations bear out that yes, in fact, the fluctuations were adiabatic: of constant entropy everywhere.

- There should be an upper limit, smaller than the Planck scale, to the temperature of the Universe in the distant past. This is also a signature that shows up in the cosmic microwave background: how high a temperature the Universe reached at its hottest. Remember, if there were no inflation, the Universe should have gone up to arbitrarily high temperatures at early times, approaching a singularity. But with inflation, there’s a maximum temperature that must be at energies lower than the Planck scale (~10^19 GeV). What we see, from our observations, is that the Universe achieved temperatures no higher than about 0.1% of that (~10^16 GeV) at any point, further confirming inflation. This is an even better solution to the monopole problem than the one initially envisioned by Guth.

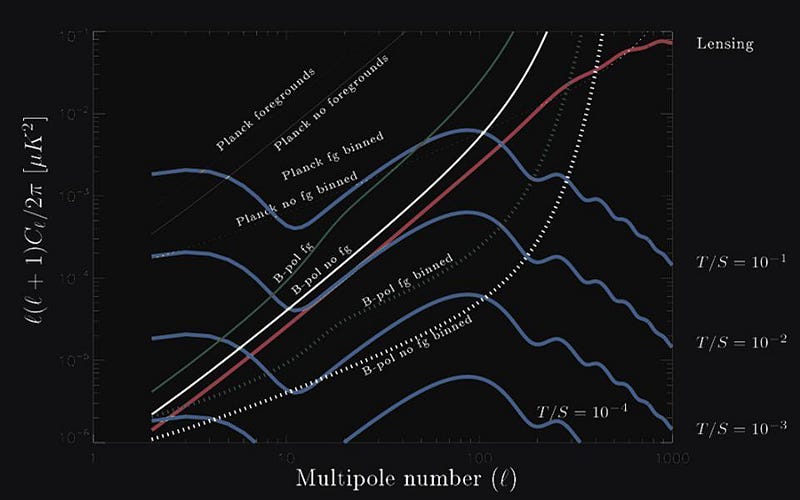

- And finally, there should be a set of primordial gravitational waves, with a particular spectrum. Just as we had an almost perfectly scale-invariant spectrum of density fluctuations, inflation predicts a spectrum of tensor fluctuations in General Relativity, which translate into gravitational waves. The magnitude of these fluctuations are model-dependent on inflation, but the spectrum has a set of unique predictions. This sixth prediction is the only one that has not been verified observationally in any way.

On all three counts — of reproducing the successes of the non-inflationary Big Bang, of explaining observations that the Big Bang cannot, and of making new predictions that can be (and, in large number, have been) verified — inflation undoubtedly succeeds as science. It does so in a way that other theories which only give rise to non-observable predictions, such as string theory, does not. Yes, when critics talk about inflation and mention a huge amount of model-building, that is a problem; inflation is a theory in search of a single, unique, definitive model. It’s true that you can contrive as complex a model as you want, and it’s virtually impossible to rule them out.

But that is not a flaw inherent to the theory of inflation; it is an indicator that we don’t yet know enough about the mechanics of inflation to discern which models have the features our Universe requires. It is an indicator that the inflationary paradigm itself has limits to its predictive power, and that a further advance will be necessary to move the needle forward. But simply because inflation isn’t the ultimate answer to everything doesn’t mean it isn’t science. Rather, it’s exactly in line with what science has always shown itself to be: humanity’s best toolkit for understanding the Universe, one incremental improvement at a time.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.