No, there isn’t a hole in the Universe

- For many years, a claim has been circulating that there’s a hole in the Universe a billion light-years wide, with no galaxies, stars, or light of any type coming from within it.

- The picture that normally accompanies it is wildly misleading, showing a dark cloud of gas and dust just a few hundred light-years away, not a large-scale cosmic structure.

- But the claim itself isn’t true; even in the deepest depths of the largest cosmic voids, lots of matter still remains, and so do stars, galaxies, and numerous electromagnetic signatures.

Somewhere, far away, if you believe what you read, there’s a hole in the Universe. There’s a region of space so large and empty, a billion light-years across, that there’s nothing in it at all. There’s no matter of any type, normal or dark, and no stars, galaxies, plasma, gas, dust, black holes, or anything else. There’s no radiation in there at all, either. It’s an example of truly empty space, and its existence has been visually captured by our greatest telescopes.

At least, that’s what some people are saying, in a photographic meme that’s been spreading around the internet for years and refuses to die. Scientifically, though, there’s nothing true about these assertions at all. There is no hole in the Universe; the closest we have are the underdense regions known as cosmic voids, which still contain matter. Moreover, this image isn’t a void or hole at all, but a cloud of gas. Let’s do the detective work to show you what’s really going on.

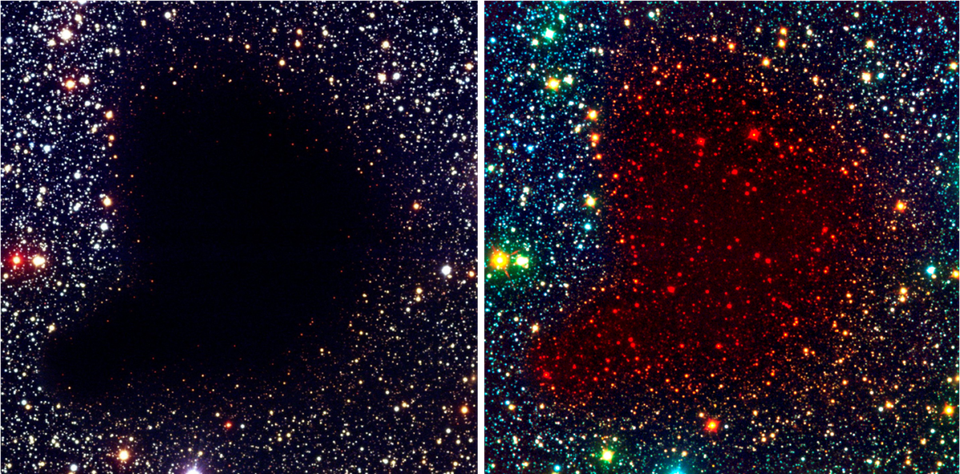

The first thing you should notice, when you take a look at this image, is that the points of light you see here are numerous, of varying brightnesses, and come in a variety of colors. The brighter ones have diffraction spikes, indicating that they’re point-like (rather than extended) sources. And the black cloud that appears is clearly in the foreground of all of them, blocking all of the background light in the center but only a portion of the light at the outskirts, allowing some of the light to stream through.

These light sources cannot be objects billions of light-years away; they are stars within our own Milky Way galaxy, which itself is only a little over 100,000 light-years across. Therefore, this light-blocking object has to be closer than those stars are, and has to be relatively small if it’s so nearby. Even if there were giant, enormous voids with no stars and galaxies in them at all, this structure couldn’t possibly be one of them.

In fact, this is simply a cloud of gas and dust that’s a mere 500 light-years away: a dark nebula known as Barnard 68. Over 100 years ago, the astronomer E. E. Barnard surveyed the night sky, looking for regions of space where there was a dearth of light silhouetted against the steady background of the Milky Way’s stars. These “dark nebulae,” as they were originally called, are now known to be molecular clouds of neutral gas, and are sometimes also known as Bok globules.

The one we’re considering here, Barnard 68, is relatively small and nearby.

- It’s located only 500 light-years away.

- It’s extremely low in mass, at just twice the mass of our Sun.

- And it’s quite small in extent, with a diameter of approximately half a light-year.

It’s true that, as far as we can tell, there are no stars inside of it, but there are plenty of stars behind it, which are revealed as soon as we look at this region of the sky in the longer wavelengths of light that are partially transparent to these “dark nebulae.”

Above, you can see an image of Barnard 68, the same nebula, in both visible light (at left) as well as in the infrared portion (at right) of the electromagnetic spectrum. The particles that make up these dark nebulae are of a finite size, and that size is extremely good at absorbing visible light. But longer wavelengths of light, like infrared light, can pass right through them. In the infrared composite image, above, you can clearly see that this isn’t a void or a hole in the Universe at all, but just a cloud of gas that light can easily pass through. (If you’re willing to look at it properly.)

Bok globules are abundant throughout all gas-rich and dust-rich galaxies, and can be found in many different locations in our own Milky Way. This includes:

- the dark clouds within the plane of the galaxy,

- the light-blocking clumps of matter found amidst star-forming and future-star-forming regions,

- the light-blocking remnants of material ejected by massive stars,

- dusty material from massive stars undergoing pulsations,

- as well as cataclysms at the end of stellar life cycles, including inside planetary nebulae and supernova remnants.

So if that’s what this image is actually showing, what about the idea behind the wildly inappropriate text that sometimes accompanies this image: that somewhere out there is an enormous void in the Universe, more than a billion light-years across, that contains no matter of any type and that emits no radiation of any type at all?

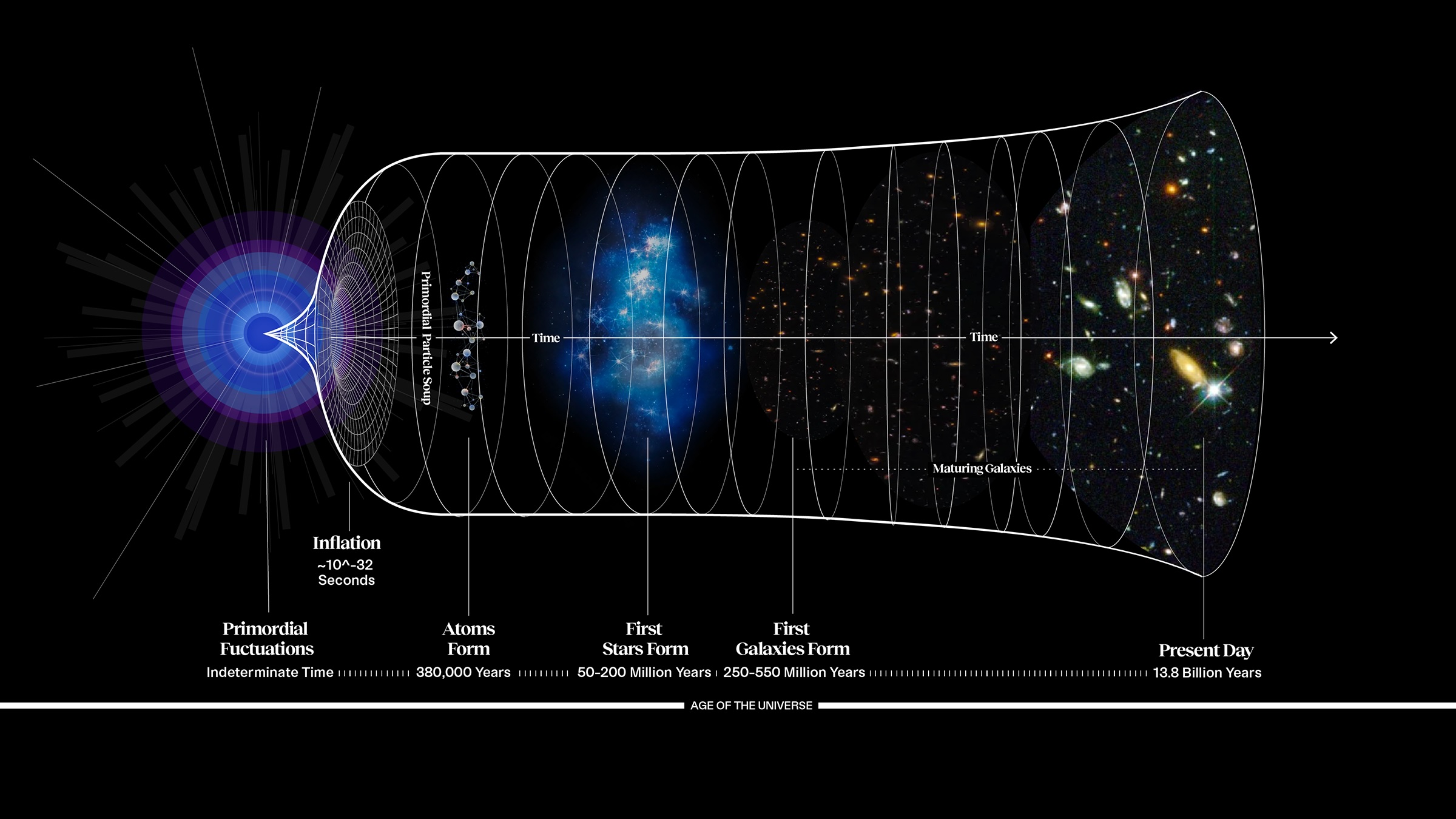

Well, there are indeed voids out there in the Universe, but they’re probably not the same as what you might think. If you were to take the Universe as it was when it began — as a nearly perfectly uniform sea of normal matter, dark matter and radiation — you’d be compelled to ask how it evolved into the Universe we see today. The answer, of course, involves:

- gravitational attraction,

- the expansion of the Universe,

- gravitational collapse,

- star formation,

- feedback from star-formation on the material that actively forms stars,

- including radiation pressure and wind particles,

- and time.

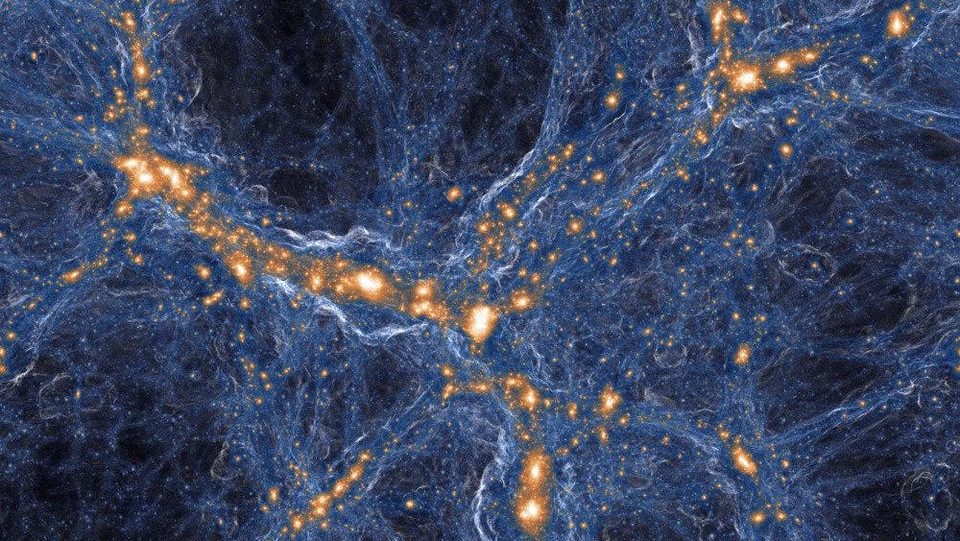

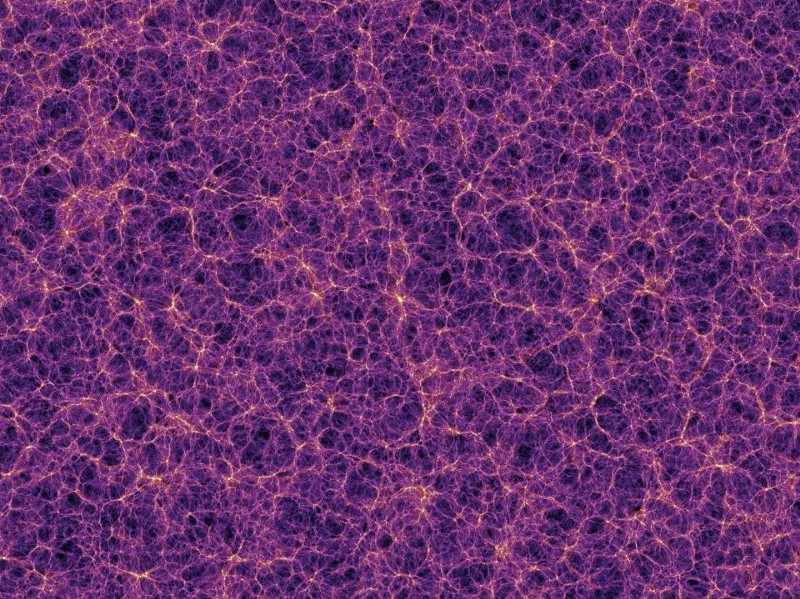

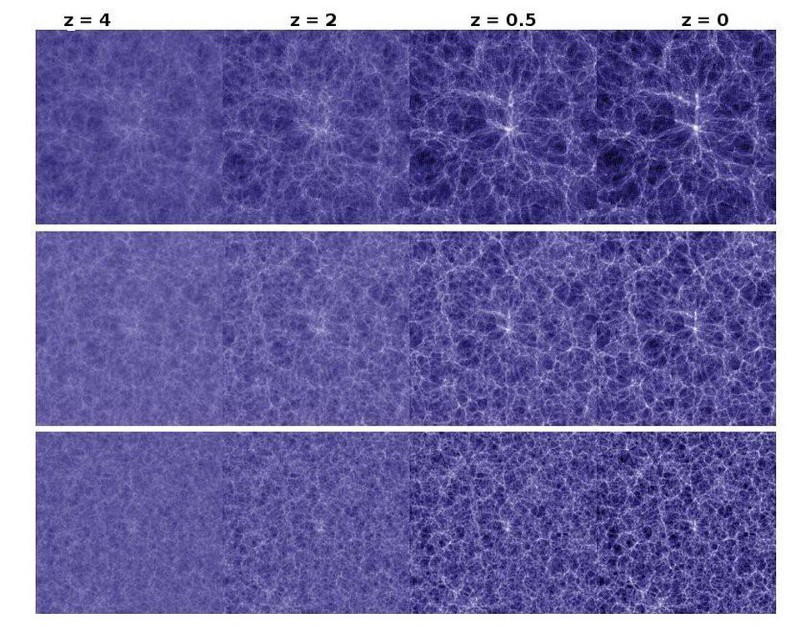

These ingredients, when subject to the laws of physics over the past 13.8 billion years of our cosmic history, lead to the formation of a vast and intricate cosmic web. Gravitational attraction is a runaway process, where overdense regions not only grow, but grow more rapidly as they accumulate more and more matter. The lower-density regions around them, even from quite a distance away, don’t stand a chance.

Just as the overdense regions grow, the surrounding regions that are underdense, of average density, or even of above-average density (but less “above-average” than the most overdense nearby region) will lose their matter to the denser ones. This process of “giving up your matter to your denser surroundings” is very effective, but isn’t a runaway process the way gravitational collapse is. Instead, when you give up some of your matter and become an underdense region, you actually expand faster than the cosmic average, making it more difficult to empty out the remaining matter.

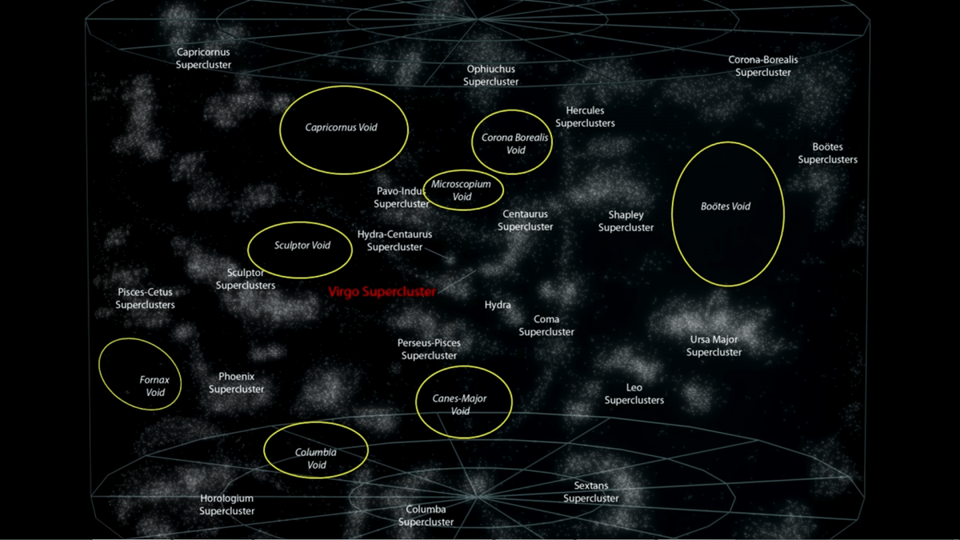

This leads to a network of galaxies, galaxy groups, galaxy clusters, and large-scale filaments of structure, with enormous cosmic voids between them.

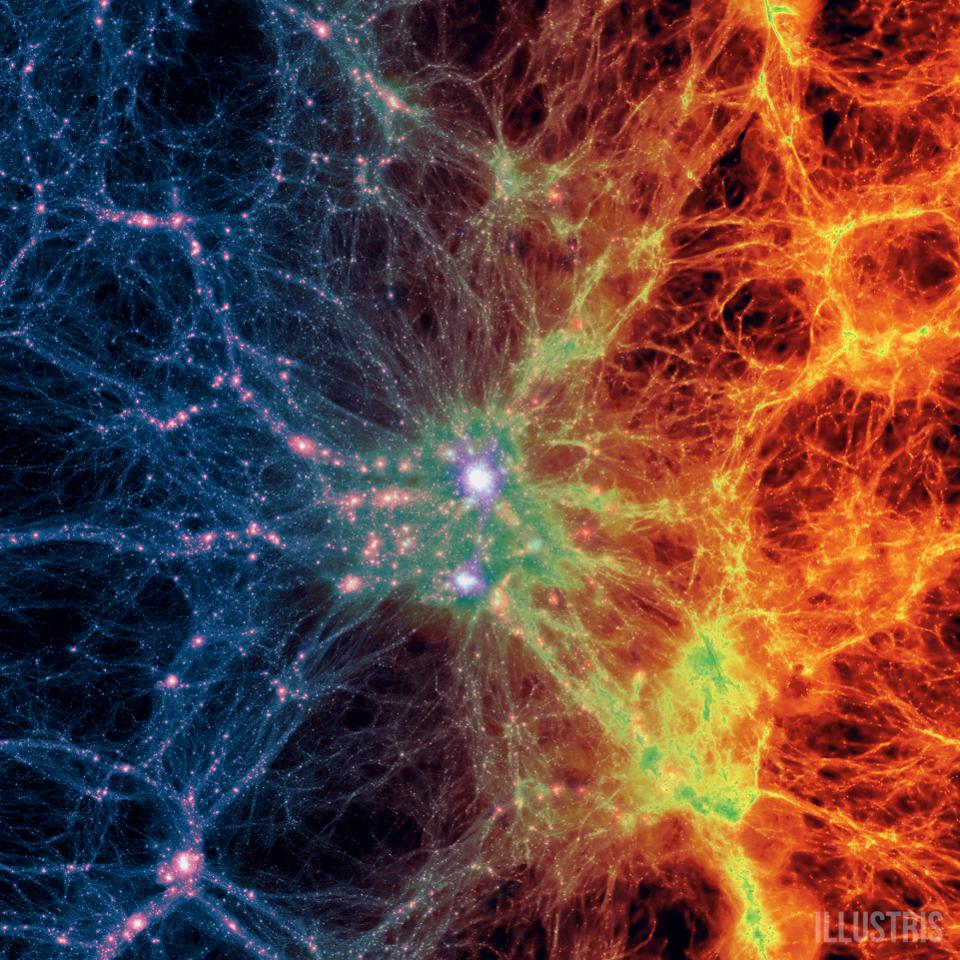

The claim, remember, is that these cosmic voids are completely empty of normal matter, dark matter, and emit no detectable radiation of any kind. Is that true?

Not at all. Voids are large-scale underdense regions, but they aren’t completely devoid of matter at all. Moreover, as you create cosmic voids on larger and larger scales, it becomes more difficult to empty out more and more of their matter.

In all of these voids, while large galaxies within them may be rare, they do exist. Even in the deepest, sparsest cosmic void we’ve ever found, there is still a large galaxy sitting at the center. Even with no other detectable galaxies around it, this galaxy — known as MCG+01–02–015 — displays enormous evidence of having merged with smaller galaxies over its cosmic history. Even though we cannot detect these smaller, surrounding galaxies directly, we have every reason to believe they are present.

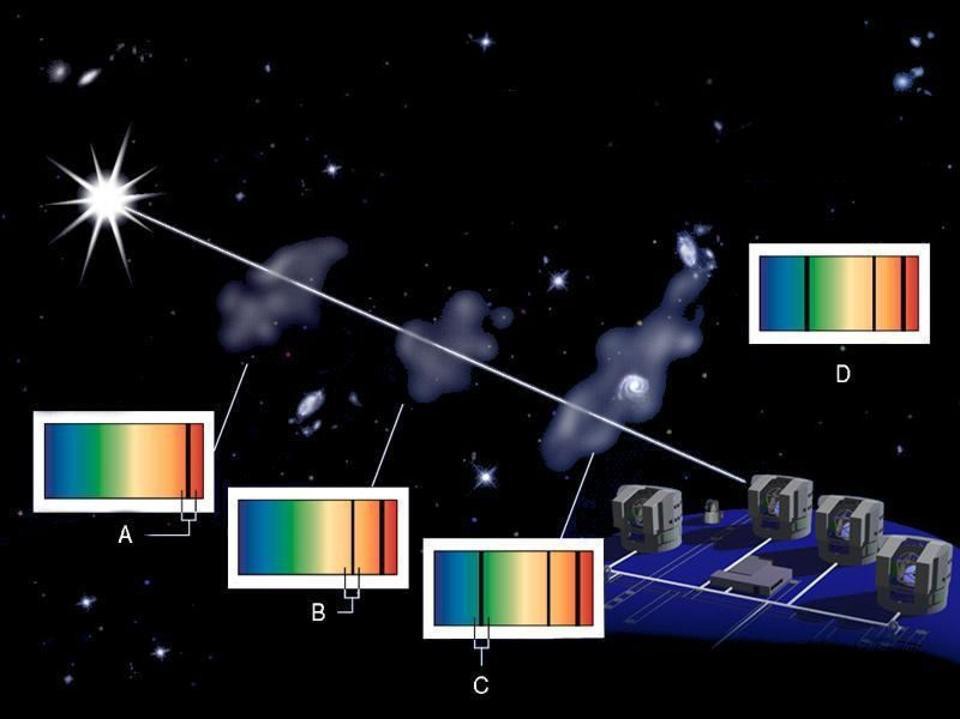

One of the ways we test for just how empty a region of space is involves examining the background starlight that passes through it and seeing, how much starlight gets absorbed at various wavelengths. We can do this in a redshift-dependent way, because neutral atoms absorb light, and hydrogen is the most common neutral atom of all. It only absorbs at a specific set of wavelengths, and so the presence (or absence) of hydrogen at a specific redshift either creates (or doesn’t create) an absorption line in, say, the continuum light from a background quasar.

We see, in many of these cosmic voids, evidence for neutral clouds of gas that are less dense than the Bok globules we talked about earlier, but that are still dense enough to absorb distant starlight or quasar light. These absorption features tell us, quite definitively, that these voids do contain matter: typically in about 50% the abundance of the average cosmic density, but on the largest cosmic scales, never less than that amount.

These are low-density regions, not regions completely devoid of all types of matter.

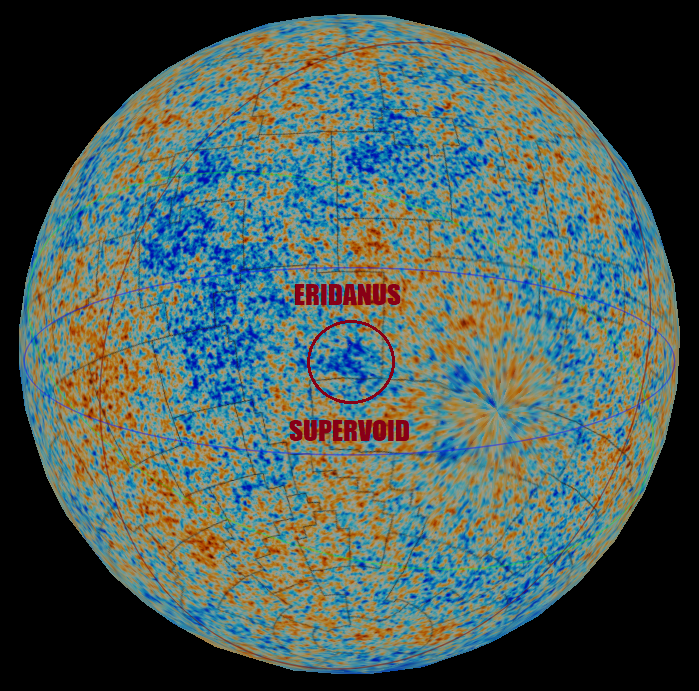

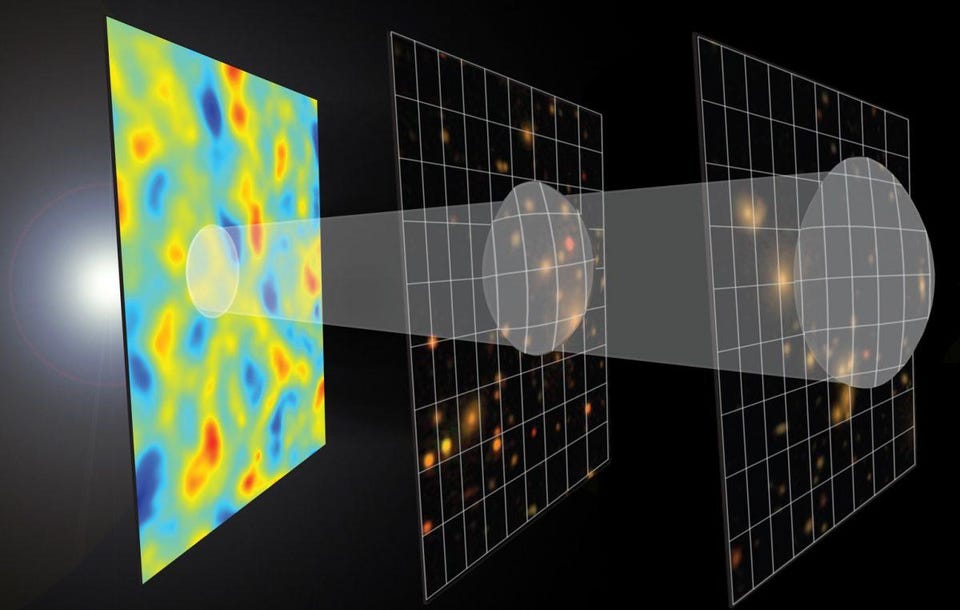

We see evidence for the presence of dark matter as well, as the background light from stars gets distorted by a combination of factors. As cosmic structure forms and the Universe expands, the gravitational potential inside a cosmic void changes in a different way than the gravitational potential changes in an average-density region, which gives rise to a shift in the light that passes through that void via the integrated Sachs-Wolfe effect.

There’s also the related but independent effect of weak gravitational lensing. The amount that light gets bent from when it’s emitted to when it arrives at your eyes is dependent on the sum total of the intervening mass between the source and the observer. Although it’s the overdense regions that have the greatest effects on bending that background light, underdense regions can also bend space, but in the opposite direction.

It isn’t just light from individual point sources that experiences these effects, either. The hot-and-cold spots that appear in the cosmic microwave background can be cross-correlated with these underdense regions, via both the integrated Sachs-Wolfe effect and from gravitational lensing.

The magnitude of how cold these cold spots get teaches us something very important: these voids cannot have zero matter in them at all. They might have just a fraction of the density of a typical region, but as far as underdensities go, a density that’s ~0% the average density is inconsistent with the data.

You might, then, begin worrying why we cannot detect any radiation or light of any type from them. It should be true that these regions would emit light. The stars that formed within them must emit visible light; the hydrogen molecules that transition from a spin-aligned state to an anti-aligned state should emit 21-cm radiation; the contracting clouds of gas should emit infrared radiation.

Why don’t we detect it? Simple: our telescopes, at these great cosmic distances, aren’t sensitive enough to pick up photons of such low densities. This is why we have worked so hard, as astronomers, to develop other methods of directly and indirectly measuring what’s present in space. Catching emitted radiation is an extremely limiting proposition, and isn’t always the best way to make a detection.

It is absolutely true that billions of light-years away, there are enormous cosmic voids in space. Typically, they can extend for hundreds of millions of light-years in diameter, and a few of them might extend for a billion light-years in size or even many billions of light-years. And one more thing is true: the most extreme ones don’t emit any detectable radiation.

But that is not because there is no matter in them; there is. It’s not because there aren’t stars, gas molecules, or dark matter; all are present. You just can’t measure their presence from emitted radiation; you need other methods and techniques, which reveals to us that these voids still contain substantial quantities of matter. And you definitely shouldn’t confuse these cosmic voids — which can indeed be a billion light-years (or more) across — with dark gas clouds and Bok globules, which are small, nearby clouds of light-blocking matter. The Universe is plenty fascinating exactly as it is; let’s resist the temptation to embellish reality with our own exaggerations.