All things being equal, the simplest explanation is usually the best. But we don’t all agree on what “simple” means.

“It is always the simple that produces the marvelous.” –Amelia Barr

The headlines always seem to be coming in, with the latest more spectacular than the last. Researchers detect possible signal from dark matter! NASA Rover Finds Active, Ancient Organic Chemistry on Mars! And yet, is there a signal from dark matter that we can go out and measure? Is there anything “organic” happening on Mars at all?

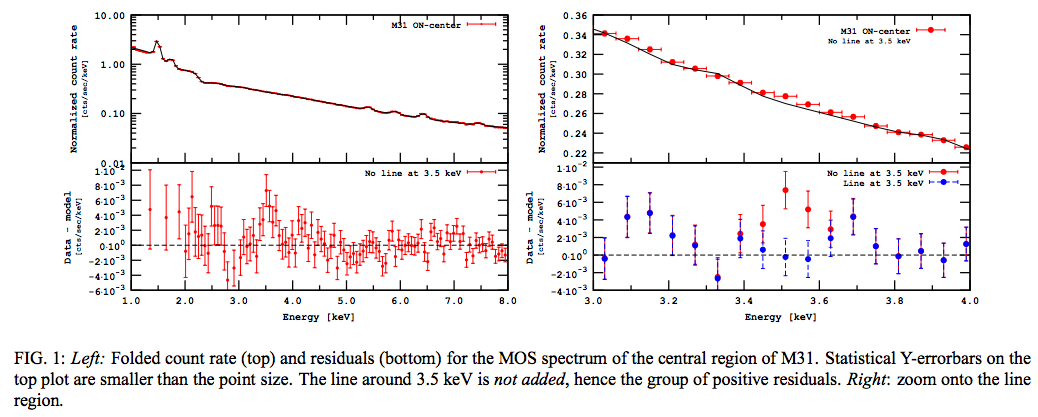

If all you do is listen to the headlines and read the press releases/articles that come out about them, you’ll probably be led to believe the odds lie somewhere between “perhaps,” “probably” and “almost definitely.” And why wouldn’t you? After all, as respects the dark matter signal, you’ll see a graph like this, coming from the scientific paper itself.

Pretty compelling that something’s there at 3.5 keV, isn’t it? Why wouldn’t it be dark matter!

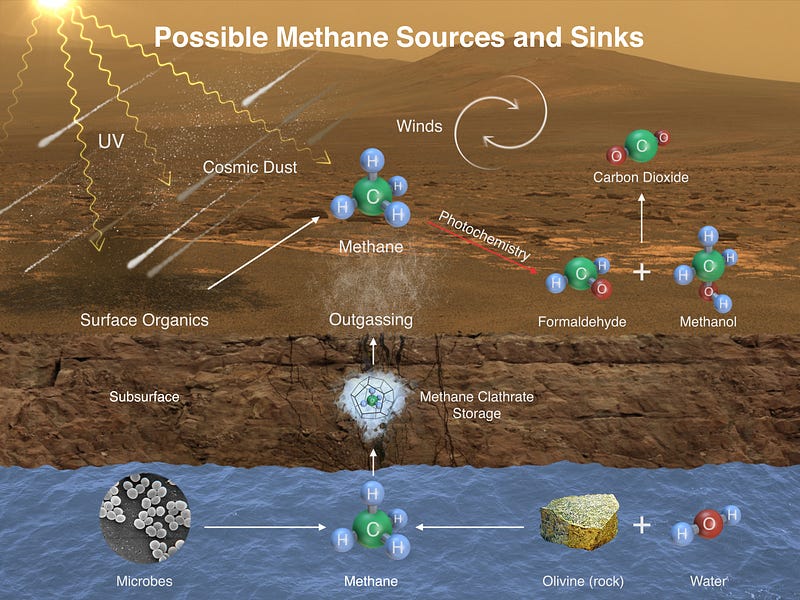

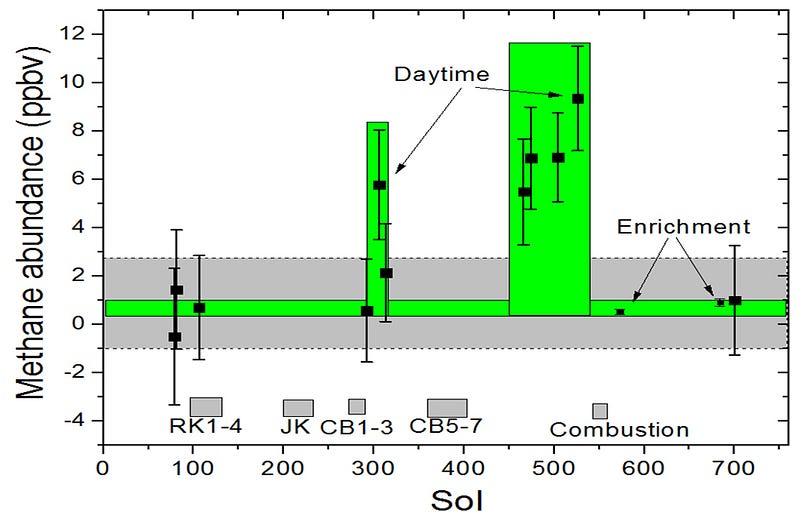

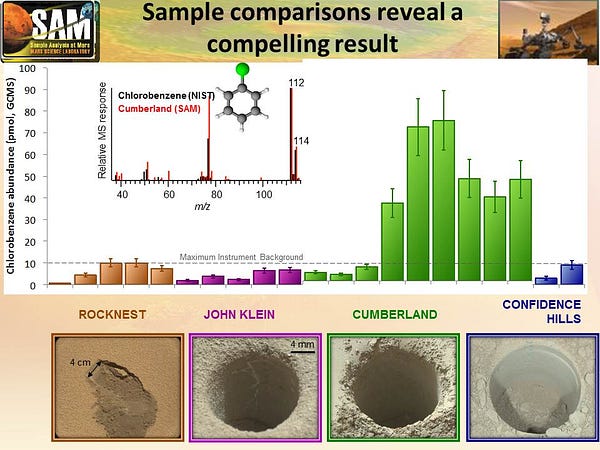

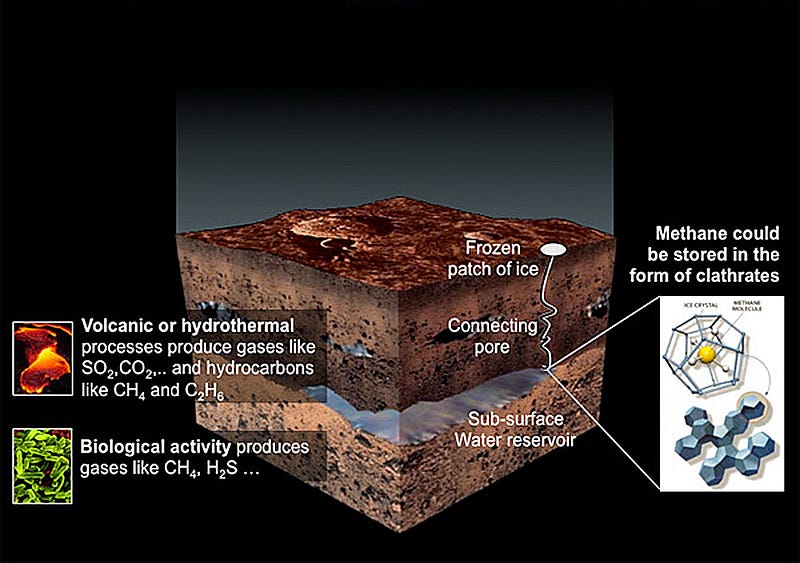

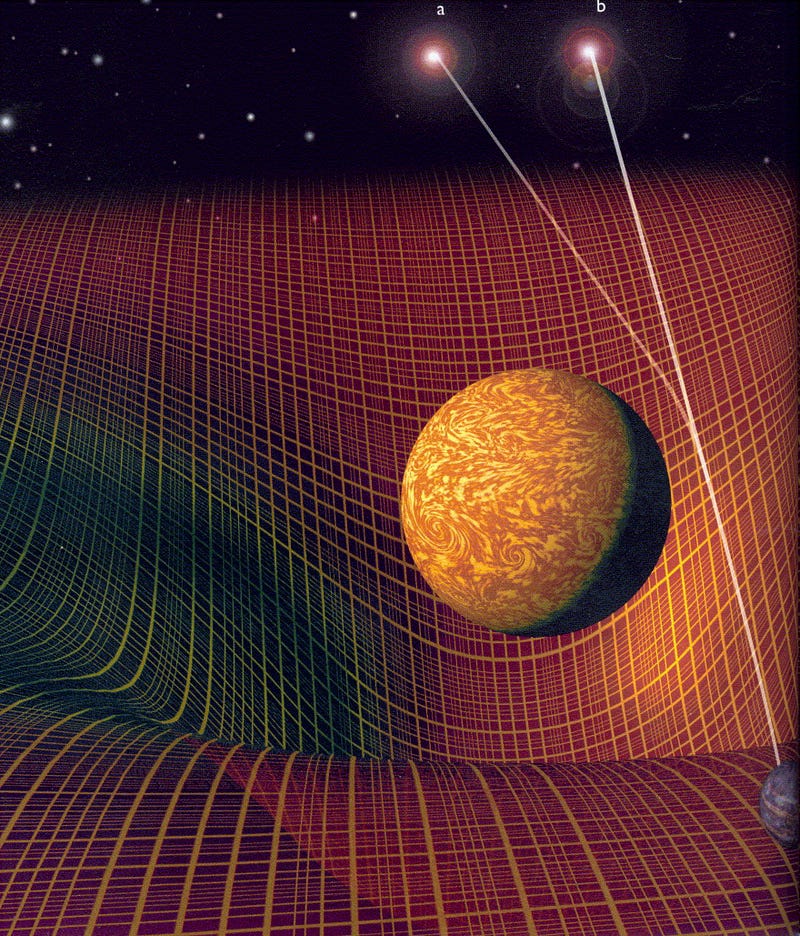

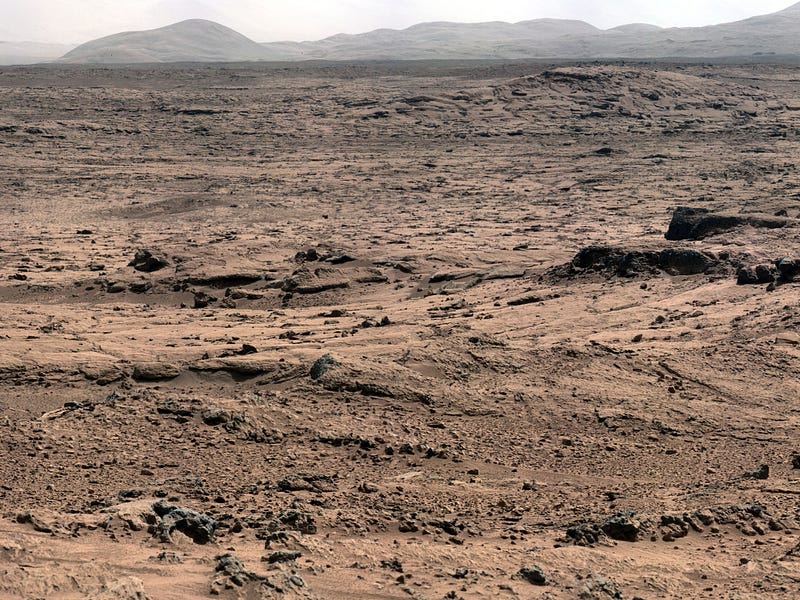

And for the Mars Curiosity rover, that’s perhaps even more compelling. After all, the rover detected a tenfold spike in methane at the same location over a very short timespan, a very interesting find! Here on Earth, methane is produced by living organisms, and then NASA went and released this official graphic.

Water below the surface could have microbes living in it, producing methane, creating pockets of gas that come up through the surface.

How could anything be simpler?

And yet, both of these scenarios are extremely doubtful. It’s probably not obvious to you why it’s doubtful, so let’s show you something where the reasoning — and the conclusions — are more than a little suspect. It’s hard to do better than this argument for dinosaurs on Venus by Carl Sagan.

Of course, Carl Sagan — despite the video’s title — doesn’t think that Venus has dinosaurs; he was going out of his way to show how some seemingly logical reasoning based on not-so-sound assumptions can lead to wildly inaccurate, speculative conclusions.

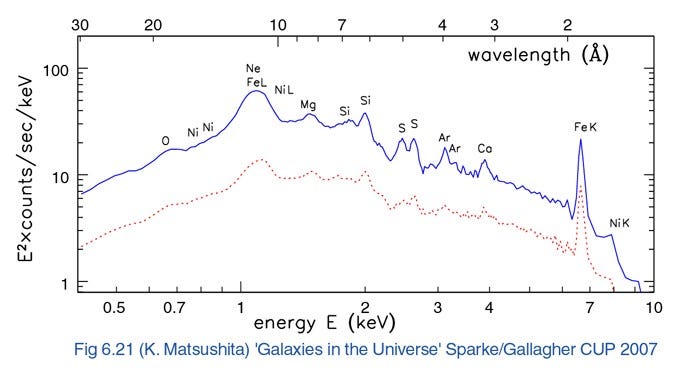

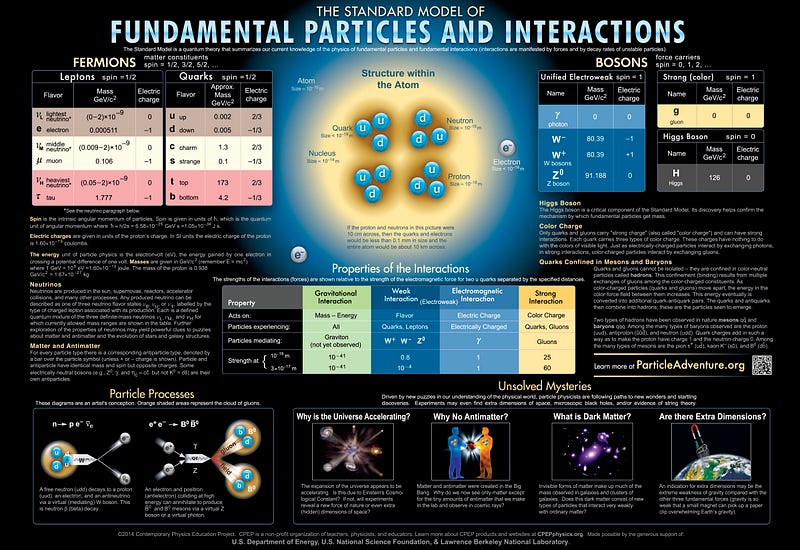

In the case of the “dark matter” signal, it is plausible that there’s a real X-ray emission line happening at 3.5 keV. But is that actually dark matter? When you consider the full spectrum of X-rays emitted around that energy — and take note of what causes those lines — it seems far less likely.

Because the emission lines we see in that energy range are all caused not by dark matter or anything exotic at all, but rather by atoms. We might be seeing evidence of a 3.5 keV emission line, but even if it turns out to be a real signal, it’s almost definitely not dark matter.

So it goes with methane on Mars as well. Yes, something is producing methane below the surface, and it does get released, apparently, in outbursts. And sure, it could be due to sub-surface life on Mars, thriving in an underground water reserve where the pressures are high enough for water to flow as a liquid. There’s also other, interesting signatures found spiking at the methane site, such as chlorobenzene.

But there could be an explanation that doesn’t require life or any organic processes at all; instead, this could be the plain old chemistry of subsurface heat catalyzing a reaction between various minerals and water, which need not even be in the liquid phase! Mars may not have a magnetically active core, but it still ought to have liquid magma within it, and hence volcanic or hydrothermal processes that occur beneath the surface.

Which one do you think is a more likely explanation?

In situations like this, where we have multiple possibilities that could give rise to the same result, we like to employ Occam’s razor, which is normally loosely interpreted as, “All things being equal, the simplest explanation is usually the best.”

You might think dark matter is a simpler explanation than atoms, while someone else might prefer the atoms. Certain people may think biological activity is the way to go to produce methane, while you may think it’s inorganic geochemistry. (Martian geochemistry? Can you have that? Martochemistry? Someone help me out.)

So, how do we decide which explanation really is the simplest when it isn’t necessarily clear? What criteria do we use?

The answer is not what most people expect. It’s not which explanation requires the fewest parameters or fewest number of inputs. It’s not which explanation allows you to get to the conclusion the fastest or in the fewest number of steps. And it’s not even the one that works the most universally.

Instead, the simplest explanation is the one that requires the fewest number of new assumptions beyond the ones we already know must exist. In other words, the simplest explanation conceivable is one that only relies on the set of known, established scientific knowledge.

That means the simplest explanation will attempt to account for this newly observed phenomenon with only the biological, chemical and physical processes already known to occur in the environment in question.

So life on Earth can be part of the “simplest” explanation, but life on Mars can’t be.

Dark matter exerting a gravitational force can be part of the “simplest” explanation, but dark matter producing radiation can’t be.

And clouds on Venus due to the chemical properties of sulfur dioxide might be part of the “simplest” explanation, but anything that even invokes the terrestrial assumption of water-based clouds would automatically be cut by Occam’s razor.

This isn’t to say the simplest explanation is always right; sometimes it turns out, after an exhaustive investigation, that the simplest explanations — the ones based on the known science alone — can’t account for what we’re seeing.

And sometimes, there really is something new out there. Sometimes, you need a new theory of gravity; sometimes, there is a new type of particle that exists; sometimes, there is going to be extraterrestrial life. The possibility that it might be there is all the motivation we need to look.

But it shouldn’t be our first assumption; our default should be to try and explain it with already known, conventional science. Only if we establish that we can’t should we turn to the alternatives.

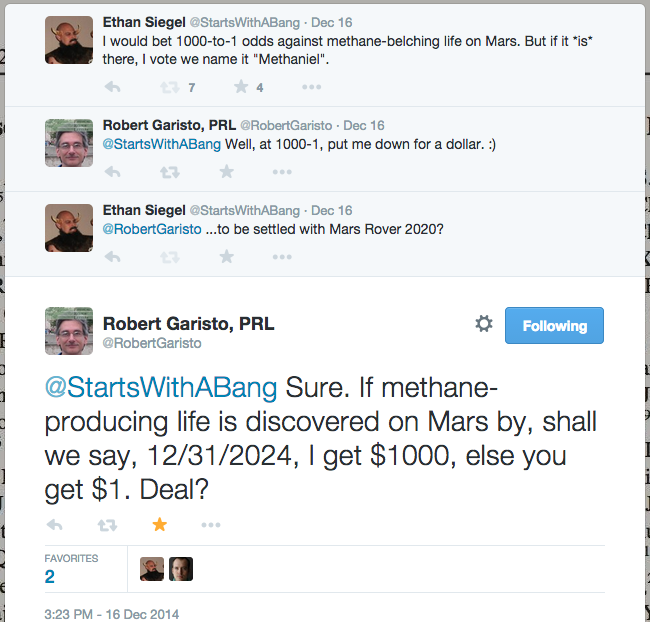

And for those of you curious as to how willing I am to stand behind this, I just put $1,000 on the line, thanks to a combination of me shooting my mouth off and Robert Garisto holding me to it.

This was a big jump for me, considering my last scientific bet was for the tidy sum of a nickel, which I happily paid when I lost.

If I lose this bet, it will be because we discovered life on another world. Which could happen, of course; we don’t know what biological processes do or don’t (or ever did) exist on our Solar System’s red planet. But 1000-to-1 odds seem fair to me, considering that the simplest explanation — one that doesn’t rely on a new discovery but rather only on the science we already know — is usually right.

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs!