Dark energy is here to stay, and a “Big Crunch” isn’t coming

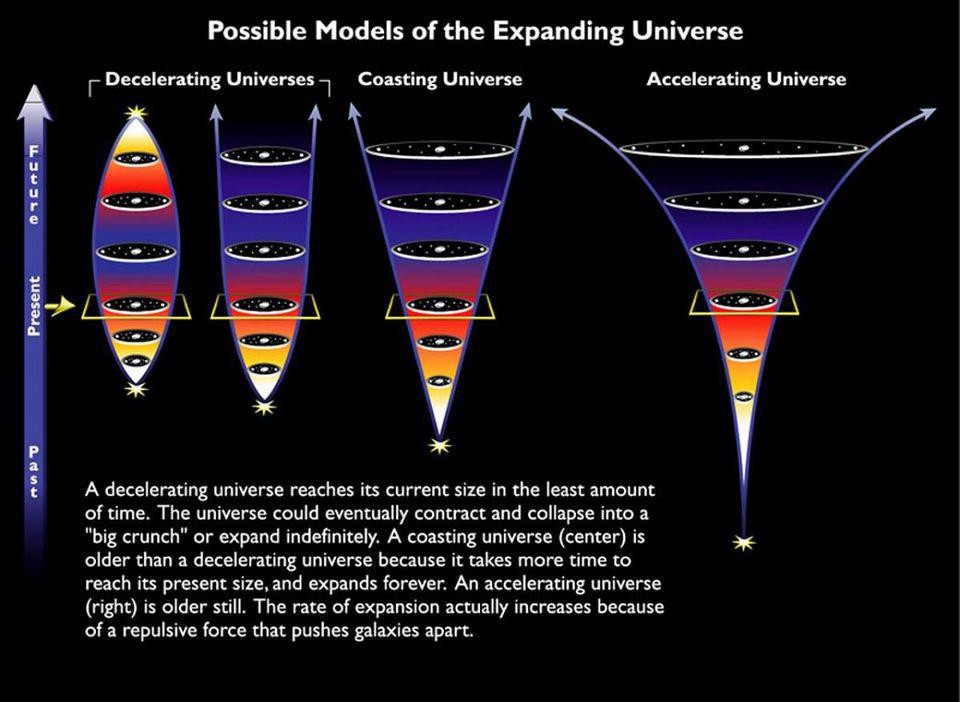

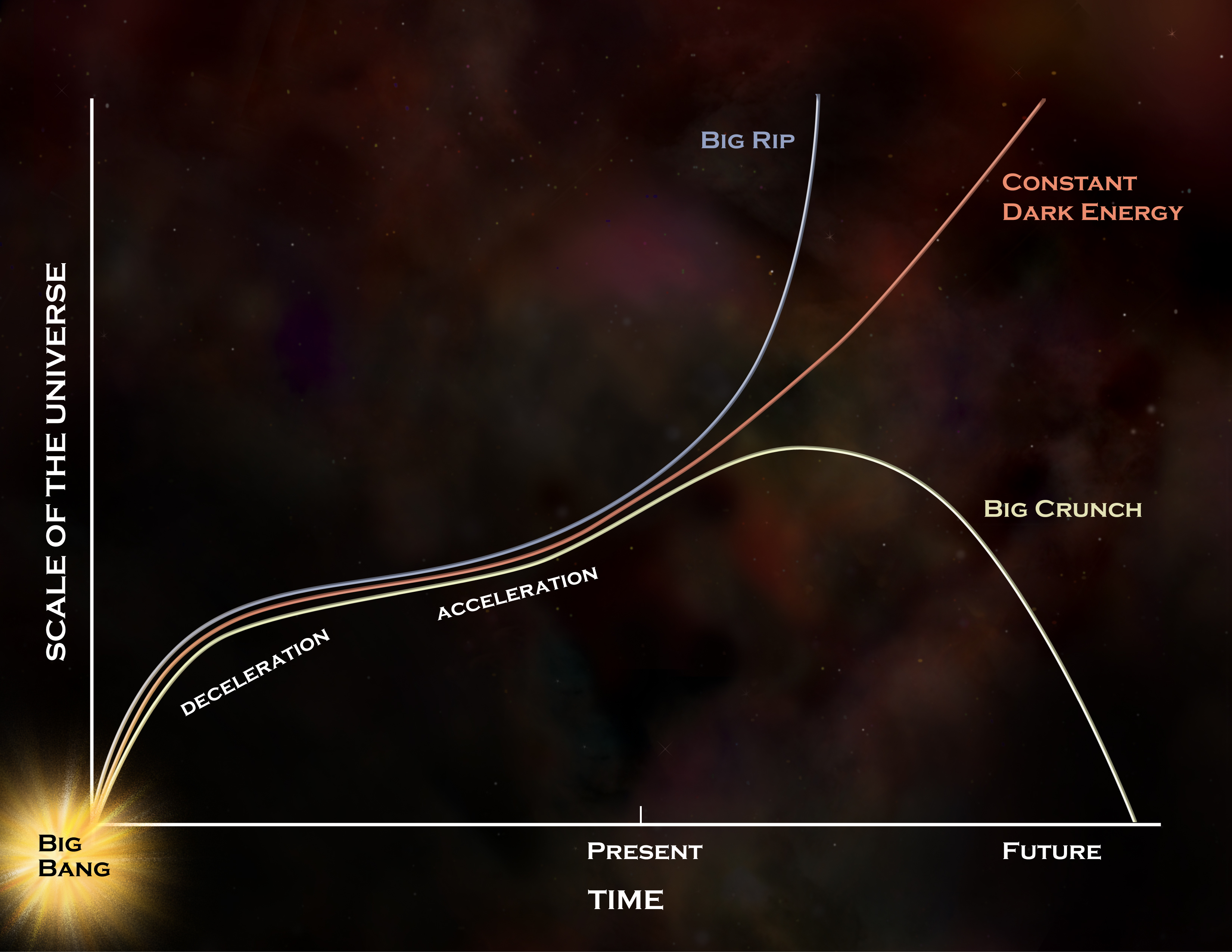

- The start of the hot Big Bang signaled the beginning of the greatest cosmic race of all: the race between expansion, which drives things apart, and gravitation, which attempts to pull things back together.

- Only if gravitation wins, and overcomes the expansion, can the Universe begin to contract again, culminating in a hot, dense, contracting state that’s the opposite of the Big Bang: a Big Crunch.

- But all observations indicate that dark energy exists, that it hasn’t changed since the dawn of the Universe, and that it won’t change moving forward. So long as that’s the case, a Big Crunch remains impossible.

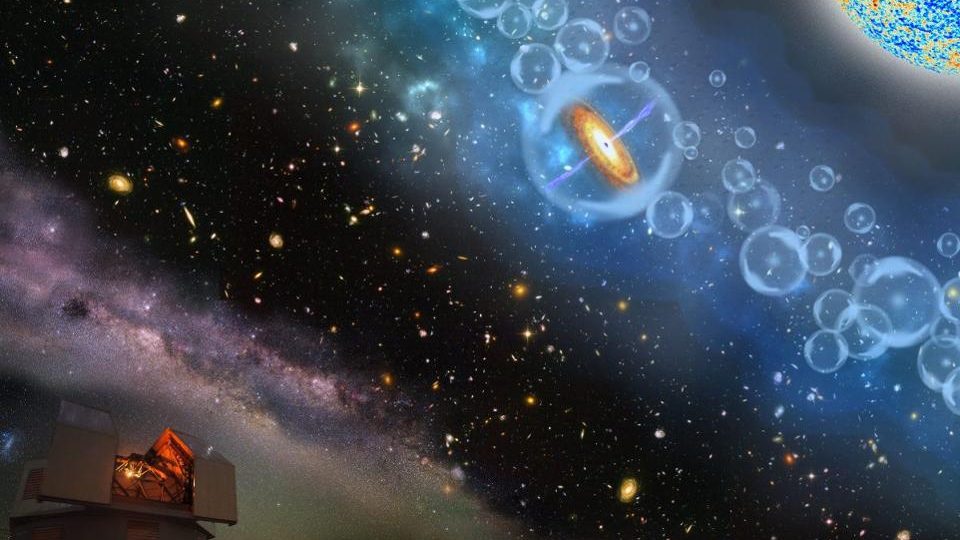

Today, the Universe is full of clues about our cosmic origins. There are galaxies everywhere, and each one is rife with stars. The stars are made out of the various chemical elements composing the periodic table, where those same stars are responsible for transmuting light elements into heavier ones via the process of nuclear fusion. Because the speed of light is finite, when we examine nearby galaxies, we’re seeing the Universe as it is today, but the farther away we look, the farther we’re seeing back in time. And the galaxies we see from earlier are fundamentally different than the ones that we see today.

The earlier galaxies are smaller, lower in mass, bluer in color, with fewer heavy elements and less-evolved structures. The light from them, in addition, has been shifted to longer and longer wavelengths by the expansion of the Universe. Because there’s a relationship between what makes up the Universe and how it expands, we can use these measurements to determine the mix of ingredients that’s present on cosmic scales.

When we do, we not only learn how to reconstruct our past history, but to predict our future history as well. What we learn is that, despite speculative reports to the contrary, a “Big Crunch” simply doesn’t add up. There’s no evidence that our Universe will turn around and start contracting, but instead will expand forever, owing to dark energy. Here’s why.

It’s easy to look out at the Universe today and wonder precisely what it is that we’re looking at. It’s easy to find questions to ponder that boggle the mind:

- What’s it made of?

- Where did it come from?

- And what, in the far future, will its ultimate fate be?

It’s important, when we engage in these exercises scientifically, to simultaneously remain open to all of the wild possibilities our imaginations can concoct, while still being consistent with the Universe we’ve observed.

If we simply look at the Universe we observe and ask the question, “What’s the simplest model that best fits the data,” we wind up with what we consider a “vanilla” Universe. If we started off with the hot Big Bang and allowed everything to expand and cool, we’d expect that the light emanating from distant objects would arrive at our eyes after being shifted to longer wavelengths by the cumulative effects of how the Universe expanded from the time the light was first emitted until the time the light arrived at our observatories.

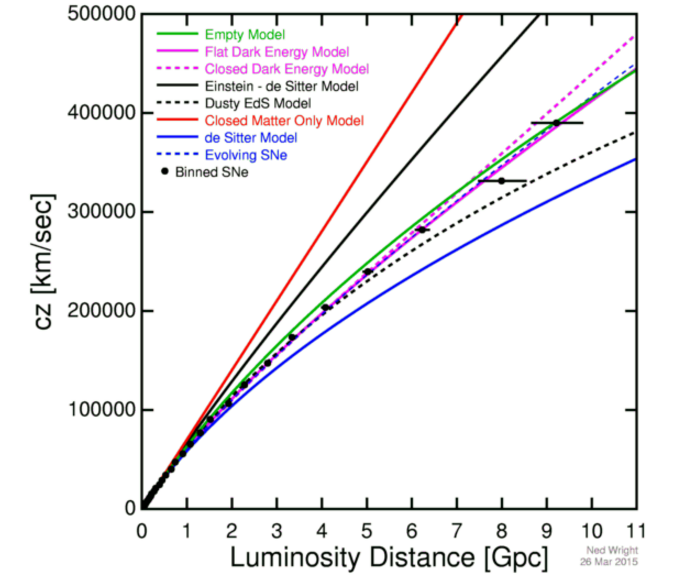

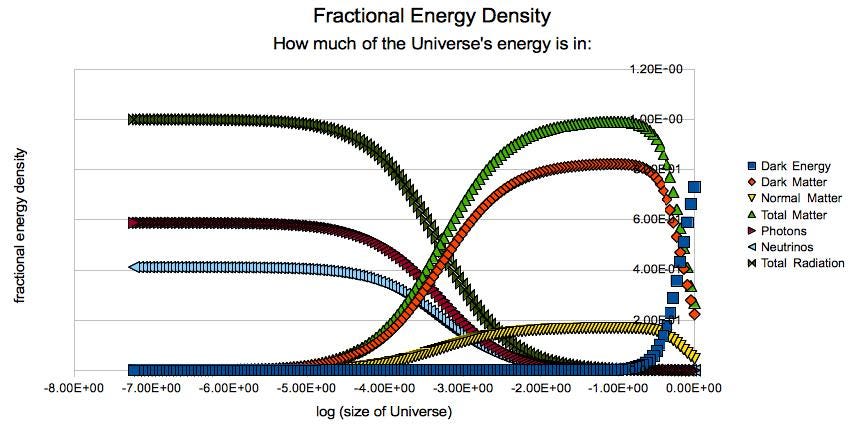

By plotting the curve of how the Universe has expanded as a function of time and comparing that with the different theoretical predictions for how a Universe with various amounts of various types of matter-and-energy evolves, one clear picture emerges as the front-runner.

This straightforward method of measuring the Universe is remarkably precise, given just how many objects we’ve been able to accurately measure over the expanse of space accessible to our instruments. Because different forms of energy evolve at different rates, simply measuring the relationship between redshift, or how much the wavelength of the observed light must differ from the light as it was when it was emitted, and distance, or how far away the object in question is, allows us to determine what makes up the Universe.

When we perform this calculation, given that we can accurately measure how fast the Universe is expanding today, we find that the Universe is made of:

- ~0.01% photons,

- ~0.1% neutrinos,

- ~4.9% normal matter,

- ~27% dark matter,

- and ~68% dark energy,

all of which leave different imprints on the Universe in a variety of ways. Although there are puzzles associated with each of them, and there’s enough wiggle-room to perhaps change things by a few percent in certain directions, this picture of what the Universe is made of is highly non-controversial on cosmic scales.

We can then go back to our understanding of the expanding Universe and ask ourselves, “If this is what the Universe is made out of, what sort of fate is in store for us?”

Again, the answer you get is incredibly straightforward. There’s a set of equations — the Friedmann equations — that relates what’s in the Universe to how the Universe expands throughout all of cosmic history. Given that we can measure the expansion rate, how the expansion rate has changed, and that we can determine what’s actually in the Universe, it’s simply a matter of using these equations to calculate how the Universe will continue to expand (or not) into the far future.

What we find is the following:

- the Universe will continue to expand,

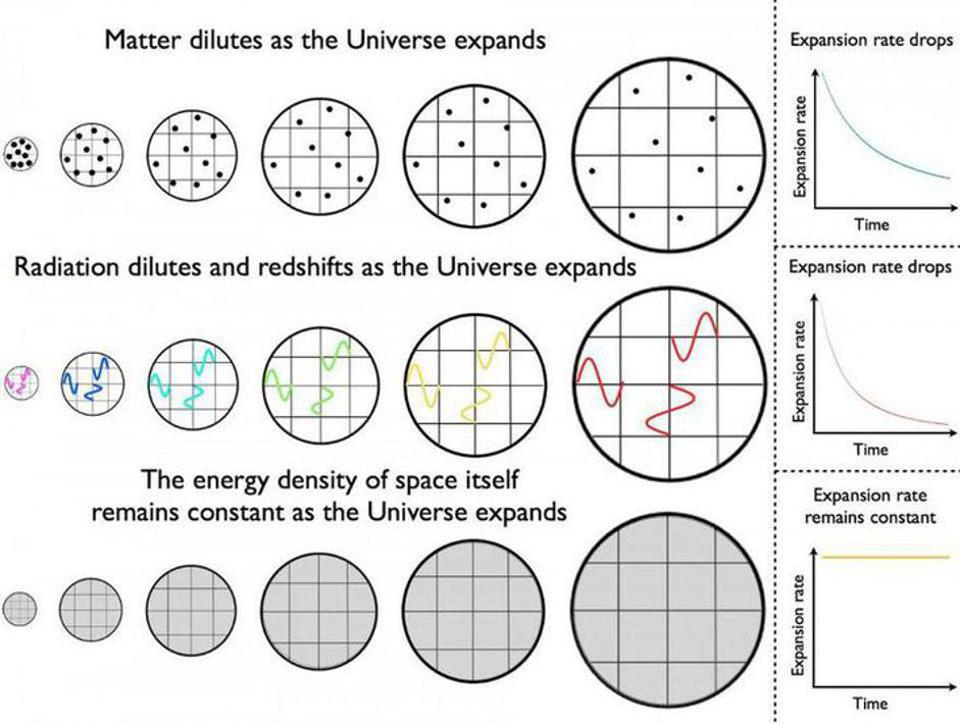

- as it does, the energy densities of photons, neutrinos, normal matter, and dark matter will all drop,

- while the energy density of dark energy will remain constant,

- which means that the Universe’s expansion rate will continue to drop,

- but not to 0; instead, it will approach a finite, positive value that’s about 80% of its value today,

- and will continue to expand, at that rate, for all eternity, even as the matter and radiation densities asymptote to zero.

In other words, the Universe will expand forever, will never see the expansion rate drop to zero, will never see the expansion reverse, and will never end in a Big Crunch.

So why, then, are some scientists so resistant to that conclusion?

Because, for better or for worse, you can always imagine that something you’ve measured — something that appears to be simple in its properties — is more complicated than you realize. If that turns out to be the case, then at that point, all bets are off.

For example, we’ve assumed, based on what we’ve observed, that dark energy has the following properties:

- it was irrelevant to the Universe’s expansion rate for the first ~6 billion years after the Big Bang,

- then, as matter sufficiently diluted, it became important,

- it came to dominate the expansion rate over the next few billion years,

- and right around the time that planet Earth was forming, it became the dominant form of energy in the Universe.

Everything we observe is consistent with dark energy having a constant density, meaning that even as the Universe expands, the energy density neither increases nor dilutes. It truly appears to be consistent with a cosmological constant.

Very importantly, this is not an ideological prejudice. From a theoretical point of view, there are very good reasons to expect that the dark energy density will not change with time or over space, but this is not the arbiter as far as what leads us to our scientific conclusions. The thing that leads us there is the quality of the data, irrespective of our preconceptions or expectations. Let’s go through both: the theoretical expectations and then the history of observations about dark energy, and then let’s finally consider the wild alternatives of what it would take — versus what evidence we have — to alter our cosmic conclusions.

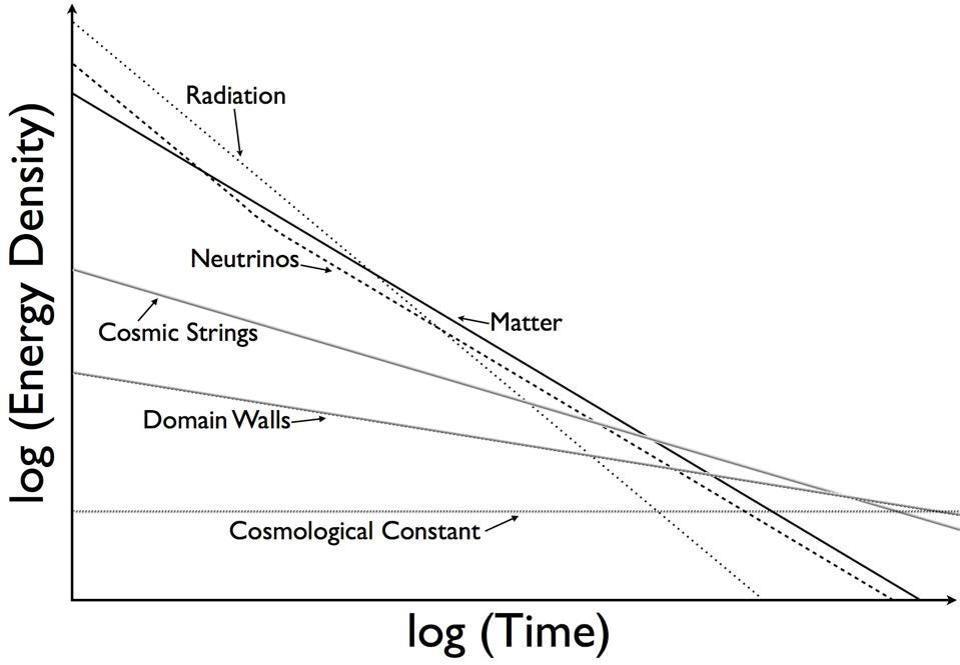

From a theoretical perspective, we can imagine that there are all sorts of “things” that are present in the Universe. As the Universe expands, the total number of “things” in the Universe remains the same, but the volume over which those things is distributed increases. In addition, if you have a large amount of kinetic energy, or if your intrinsic energy is related to a space-related property like wavelength, then the expansion of the Universe can alter the energy inherent to each thing. You can calculate, for each species of “thing” you can imagine — things like radiation, neutrinos, normal matter, dark matter, spatial curvature, cosmic strings, domain walls, cosmic textures, and a cosmological constant (which is the same as the zero-point energy of empty space) — how their energy densities will change as the Universe expands.

When we work this out, we notice that there’s a simple but straightforward relationship between the energy density of each species, the scale of the Universe, and what General Relativity describes as the pressure of each species. In particular:

- Radiation dilutes as the scale of the Universe to the 4th power, and the pressure is +⅓ multiplied by the energy density.

- All forms of matter dilute as the scale of the Universe to the 3rd power, and the pressure is 0 multiplied by the energy density.

- Cosmic strings and spatial curvature both dilute as the scale of the Universe to the 2nd power, and the pressure is -⅓ multiplied by the energy density.

- Domain walls dilute as the scale of the Universe to the 1st power, and the pressure is -⅔ multiplied by the energy density.

- And a cosmological constant dilutes as the scale of the Universe to the 0th power, where the pressure is -1 multiplied by the energy density.

When you have a particle species like a neutrino, it behaves as radiation while it’s relativistic (moving close compared to the speed of light), and then transitions to behave as matter as it slows down due to the expanding Universe. You’ll notice, as you look at these various possibilities for the Universe, that the pressure is related to the energy density in increments of factors of ⅓, and only changes when species change their behavior, not their intrinsic properties.

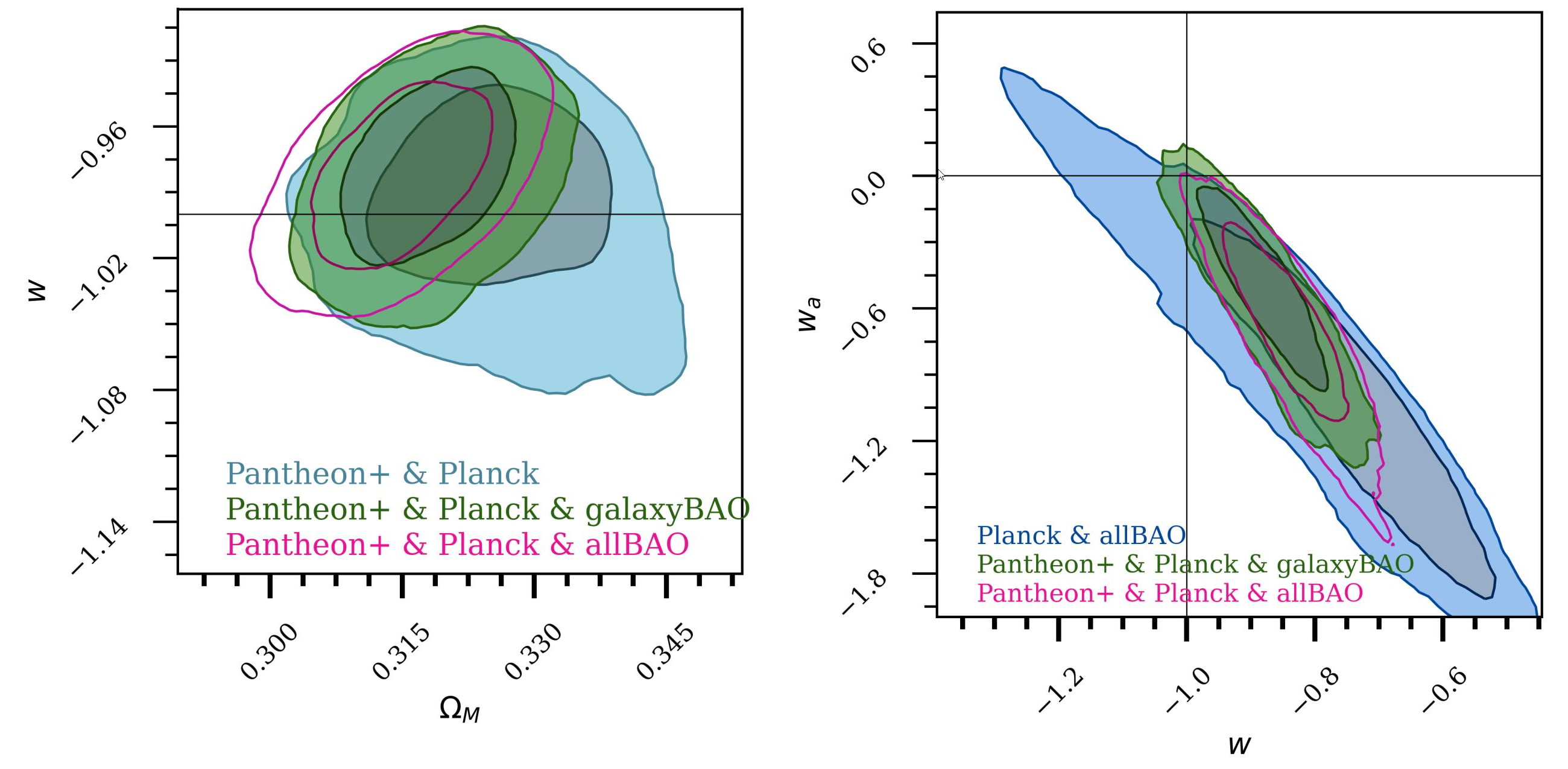

When we first uncovered the presence of dark energy, we weren’t able to measure its properties well at all. We could tell it wasn’t matter or radiation, as we could tell that it had some sort of pressure that was negative overall. However, as we gathered better data, particularly:

- from type Ia supernovae,

- from the imperfections in the cosmic microwave background,

- and from measuring how the Universe’s large-scale structure evolved over cosmic time,

our constraints began to improve. By the year 2000, it was clear that dark energy’s pressure was more negative than cosmic strings or spatial curvature could account for. By the mid-2000s, it was clear that dark energy was most consistent with a cosmological constant, but with an uncertainty that was still pretty large: of about ±30-50%.

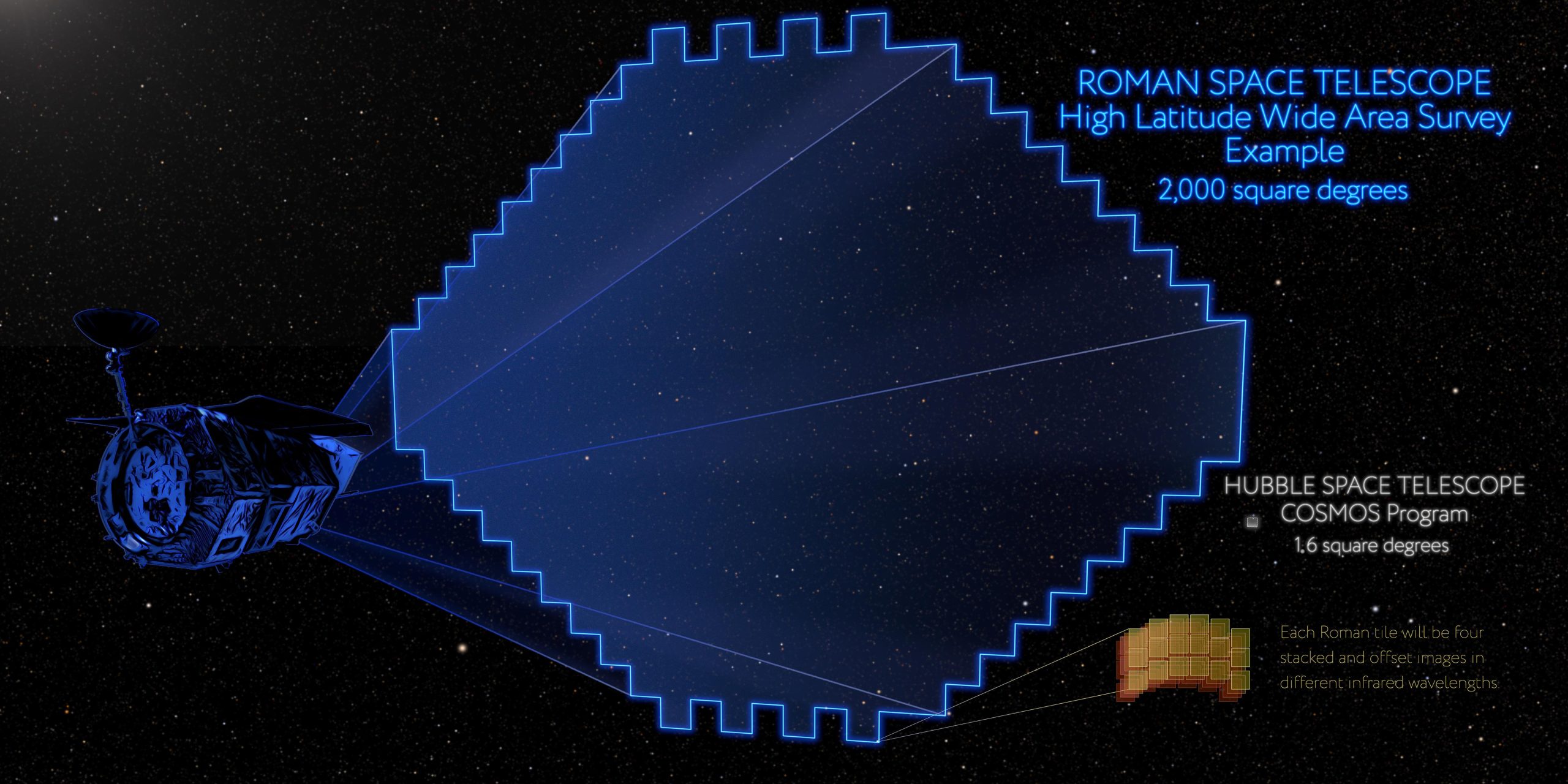

However, measurements of the cosmic microwave background’s polarization from WMAP, improved measurements by Planck, and measuring how galaxies are correlated throughout space and time through surveys like the two-degree field, WiggleZ, and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey gradually reduced those errors. By the early 2010s, dark energy still looked like a cosmological constant, but the uncertainties were down to ±12%. By the late 2010s, they were down to ±8%. Today, they sit at around ±7%, with NASA’s upcoming Nancy Roman Telescope poised to reduce that uncertainty down to just ±1%.

Both theoretically and observationally, we have every indication that dark energy is a cosmological constant. We know its pressure is equal to -1 multiplied by its energy density, and not -⅔ or -1⅓. In fact, the only wiggle-room we have is that there’s some tiny variation, across either space or time, that lies below the limits of what we’ve been able to detect. Both theoretically and observationally, there’s no reason to believe that such a variation exists.

But that will never stop theorists from doing what they do best: playing in the proverbial sandbox.

Whenever you have an observational or experimental result that doesn’t align with your expectations, what we typically do is modify the standard theory by adding something new in: a new particle, a new species, or a modification to the behavior of a known-to-exist species. Each new ingredient can have one or more “free parameters” to it, enabling us to tweak it to fit the data, and to extract new predictions from it. In general, a “good idea” will explain many different discrepancies with few free parameters, and a “bad idea” will explain only one or two discrepancies with one or two parameters.

Where do dark energy models that lead to a Big Crunch fall, according to this criteria? They add one or more new free parameters, without explaining a single unexpected result. It doesn’t even fall along the good idea-bad idea spectrum; it’s simply unmotivated speculation, or as we call it in professional circles, complete garbage.

It doesn’t mean, ultimately, that dark energy won’t undergo some sort of unexpected transition, and that its properties won’t change in the future. It doesn’t mean that it’s impossible for such a transition to change the contents of the Universe, even causing it to reverse course. And it doesn’t mean that a Big Crunch is an impossible fate for us; if dark energy changes in ways we don’t anticipate, it could indeed happen.

But we shouldn’t confuse “it isn’t ruled out” with “there’s any evidence, at all, indicating this ought to be the case.” People have been modifying dark energy for over 20 years now, playing in the sandbox to their heart’s content. In all that time, up to and including the present, not a single shred of evidence for dark energy’s unexpected evolution has ever appeared. While some may argue that their explanations are beautiful, elegant, or attractive in some way, it’s worth remembering the aphorism known as Hitchens’ razor: “What can be asserted, without evidence, can be dismissed without evidence.” According to all the evidence, dark energy is here to stay, and a Big Crunch, while possible, just doesn’t describe the future fate of the Universe we happen to live in.