Celebrate The Earliest Equinox Since 1896 This March 19, Thanks To Science

No one has seen an equinox this early since the 19th century. And you’d better get used to it.

This year, on March 19, 2020, the equinox will occur. For a brief moment in time, the Earth’s axis will be oriented perfectly perpendicular to the Sun’s rays, marking the instant where we transition from one season (winter in the northern hemisphere, summer in the southern) to the next (spring in the northern hemisphere, autumn in the southern). This marks the first year since 1896 where the equinox occurs on March 19, rather than 20 or 21, for all timezones in the United States.

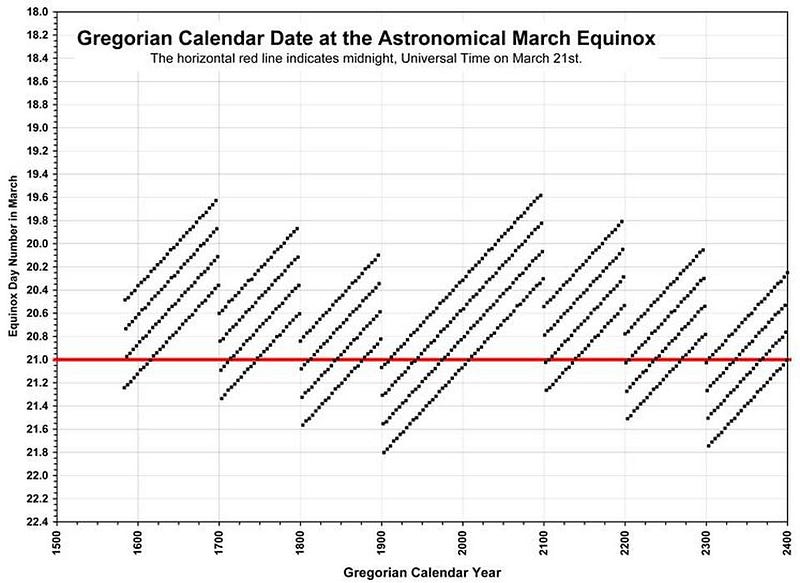

Those of us who grew up in the 20th century likely remember the equinox typically occurring on either March 20 or 21, never seeing a March 19 equinox until the onset of this new century. And now, as we move forward, the equinox will get earlier and earlier every four years, with even parts of Europe and Africa experiencing a March 19 equinox later this century. But this is exactly according to plan, and the science of our calendar explains why.

Unlike the solstices, where the Earth’s poles are maximally tipped towards the Sun in their orbit (June for the northern hemisphere, December for the southern hemisphere), the equinoxes represent that moment that’s exactly in between: where both hemispheres receive sunlight in equal amounts. We typically talk about the equinox occurring on a specific day, but it’s actually a particular instant in time, occurring in 2020 at 11:50 PM ET (8:50 PM PT) on March 19.

Each year, even as the Earth orbits on its axis and revolves around the Sun, our planet returns to the same relative position and orientation in our orbit. In an ideal world, this would line up exactly with the calendar we keep. But there aren’t exactly an even number of days in the year; according to the best math we have, there are 365.242189 days in a year. In order to keep time as accurately as possible yet still have a whole number of days in each year, we’ve adopted the Gregorian Calendar and its system of Leap Years.

This year, 2020, is a Leap Year, as all of you likely remember. In order to keep our terrestrial calendar in line with the Earth’s orbit, our Leap Years obey the following rules:

- Every year that isn’t divisible by 4 (like 2018, 2019, 2021, 2022, etc.) has 365 days in it, with February having 28 days only.

- Every year that is divisible by 4 (like 2016, 2020, 2024, 2028, etc.) gets 366 days to it, with February getting a 29th day during these years.

- And every year that ends in “00,” like 1600, 1700, 1800, 1900, 2000, 2100, etc, only gets a February 29th if it’s also divisible by 400.

In other words, 1800 wasn’t a Leap Year; 1900 wasn’t a Leap Year; 2000 was a Leap Year; 2100 won’t be a Leap Year, and so on. All told, this means we’re presently accounting for 365.2425 days in each year, on average, which is a very good approximation for 365.242189.

But getting something precisely right on average doesn’t mean it’s going to be exactly the same year after year or century after century. In 2019, for example, the March equinox occurred in the United States on March 20, at 5:58 PM ET (2:58 PM PT): some 18 hours later than it’s occurring in 2020. The reason it’s so much earlier this year as compared to last year is because of the insertion of Leap Day this past February 29th.

Whereas “only” an extra 0.242189 days (about 5 hours and 49 minutes) needed to be added to our calendar to keep 2020 in line with where we were in 2019, we instead added a whole entire 24-hour day. As a result, 2020’s equinox occurs about 18 hours earlier than 2019’s did: enough to push it back to March 19 for all United States timezones.

And yet, those of us who remember growing up and living a substantial portion of our lives in the 1900s quite accurately remember that the 20th century never had a March equinox on the 19th. This, too, is true. In fact, the last year that saw a March 19 equinox, or any equinox as early as 2020 will experience, was 1896.

Think about the significance of that year: 1896. In terms of a calendar, 1896 was the last Leap Year in a string of 24 consecutive every-four-years Leap Years, from 1804 to 1896, inclusive. Remember, with 365.242189 days required to account for a full year, approximating that by having a Leap Year every four years (which is an average of 365.25 days-per-year) actually puts us a little bit ahead. Each time we make that approximation — that 1-in-4 years are a Leap Year — we wind up keeping time “too fast” by about 45 minutes every four years.

Compared to 1800, therefore, the 1896 calendar year saw an equinox that was approximately 18 hours earlier than the 1800 equinox. And all of this would have continued to get worse all through the 20th century if we had made 1900 a Leap Year as well. But that’s the huge advantage of the Gregorian Calendar over the Julian Calendar: years that end in “hundred” are only Leap Years if they’re divisible by 400.

1900, therefore, wasn’t a Leap Year. And instead of racing ahead on our calendar by another 45 minutes from 1896 to 1900, we instead let the calendar “catch up” by a full 23 hours and 15 minutes by not having a Leap Year. That one difference — between having a Leap Year in a turn-of-the-century year versus not — explains why the equinoxes were always on March 20 or 21 in the 1900s, whereas they frequently occurred on the 19th towards the end of the 1800s.

But the year 2000 was a Leap Year, because it was a turn-of-the-century year that was also divisible by 400. Whereas years like 1800, 1900, and 2100 cause the calendar to “catch up” by 23 hours and 15 minutes relative to the calendar four years prior (in 1796, 1896, and 2096, respectively), the year 2000 behaved just like any other Leap Year: allowing the calendar to slip by another 45 minutes versus 1996.

In other words, as long as you know when the equinox happened the last year, you can know when the next year’s equinox will be by following two rules.

- The equinox gets later by 5 hours and 49 minutes, cumulatively, versus the previous year when there’s no Leap Year.

- The equinox gets earlier by 18 hours and 11 minutes each Leap Year versus the prior year.

When we do the math, we can determine what types of changes this causes in the equinoxes over long periods of time.

It means that the latest-in-the-year equinoxes always occur when these three conditions line up:

- it’s the last year before a leap year (like 1999, 2003, 2007, 2011, 2015, 2019, etc.),

- it’s an early-in-the-century year after a turn of the century that wasn’t a Leap Year (the early 1700s, 1800s, 1900s, 2100s, etc.),

- and this is maximized after three consecutive non-Leap Year centuries (e.g., the early 1900s, 2300s, 2700s, etc.).

Similarly, that means the earliest equinoxes occur on Leap Years that are towards the end of centuries, particularly in centuries where the turn-of-the-century was also a Leap Year. As the 21st century continues to progress, we’ll see that every 4 years, on average, the equinox will occur 45 minutes earlier than 4 years prior. By the year 2096, we’ll have the earliest equinox for another 400 years: March 19 at 10:04 AM ET (7:04 AM PT).

But all of that will change when the year 2100 arrives, because that year won’t be a Leap Year. From 2097 through 2103, the equinox will get pushed forward by 5 hours and 49 minutes each year, cumulatively. In 2103, in fact, the March equinox will once again occur on March 21 over parts of the United States: something that won’t occur in the United States throughout the entire 21st century.

The fact that 2100 isn’t a Leap Year pushes the equinox later in the calendar, something that will occur again in 2200 and still again in 2300. This means that the equinox of 2303 will be the latest one of the next 400 years: where it will actually occur in the afternoon of March 21 in New York. But right now, we’re living in an era where the equinoxes are not only the earliest they’ve been in recent memory, but they continue to get earlier with every 4 years that passes, with Leap Years marking the earliest equinoxes of all.

This year, 2020, marks the first year since 1896 where every United States timezone will experience the equinox on March 19. This will get more severe every 4 years, culminating in an equinox so early in 2096 that even Europe, Africa, and much of Asia will have a March 19 equinox. But this is just a natural part of the cycles of our calendar and how we keep time.

The equinox is migrating exactly as anticipated, and by the 2050s we’ll start experiencing equinoxes even earlier than anything seen in the 19th century as well. But all of that will change again once the calendar ticks past 2100. Although few of us will be around to witness it, March equinoxes in the early 2100s will always fall on March 20 or 21, and never on the 19th, not even on a Leap Year, not for many decades. Enjoy the earliest equinox of your lifetime this year, but come back four years from now and every four years after that, where we’ll keep breaking that record until the century’s end.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.