Ask Ethan: Which Movies Get The Science Of Time Travel Right?

It’s one of the most common tropes in science fiction. But which movies actually get the science right?

The way we travel through time, at a speed of one second per second, is so boring that we take it for absolute granted. Yet according to Einstein’s theory of relativity, we can not only travel forward through time at different rates by accelerating close to the speed of light, we could potentially travel either forwards or backwards by constructing a bridge through two disconnected locations in spacetime. Time travel, either forwards or backwards, has long been a staple of our imaginations and our stories; who wouldn’t want to explore the unseeable future or go back in time to right a past wrong? But getting those stories to be scientifically accurate is another job entirely. Which movies do the best at that? That’s what Ernio Hernandez wants to know, as he asks:

I’m admittedly a fan of time-travel movies (however they explain it). What movie makes the best case for using this plot device accurately?

Let’s take a look at what makes a good time travel movie, and see how your favorites stack up.

If your goal is scientific accuracy, we have to understand what traveling through time looks like. One of the most revolutionary things that Einstein’s relativity brought us was the notion that space and time aren’t separate, absolute entities, but that they’re inextricably linked. The Universe is made of a four-dimensional fabric known as spacetime, and all objects, particles, and radiation exist within it. This leads to an odd, not-necessarily-intuitive phenomenon: your motion through time is affected by your motion through space, and vice versa.

Any object existing within this spacetime will immediately notice three things:

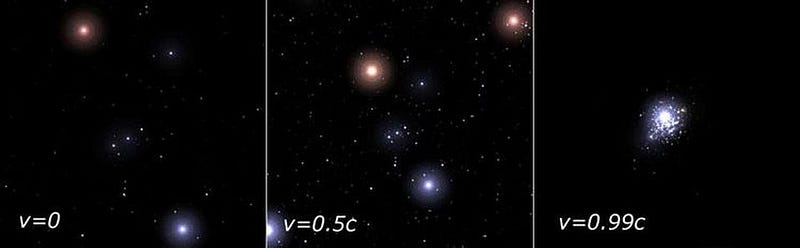

- other objects in motion relative to them will have their distances shortened and their clocks time-dilated,

- relative to them, light always moves at the same speed: c, the speed of light in vacuum, and

- their motion through spacetime is determined by the curvature of spacetime, which depends on the matter-and-energy around them in the Universe.

If you’re in a particular, fixed frame of reference (like stationary on the Earth’s surface), then anyone who goes in motion relative to you will move a larger amount through space, meaning they’ll move a smaller amount through time.

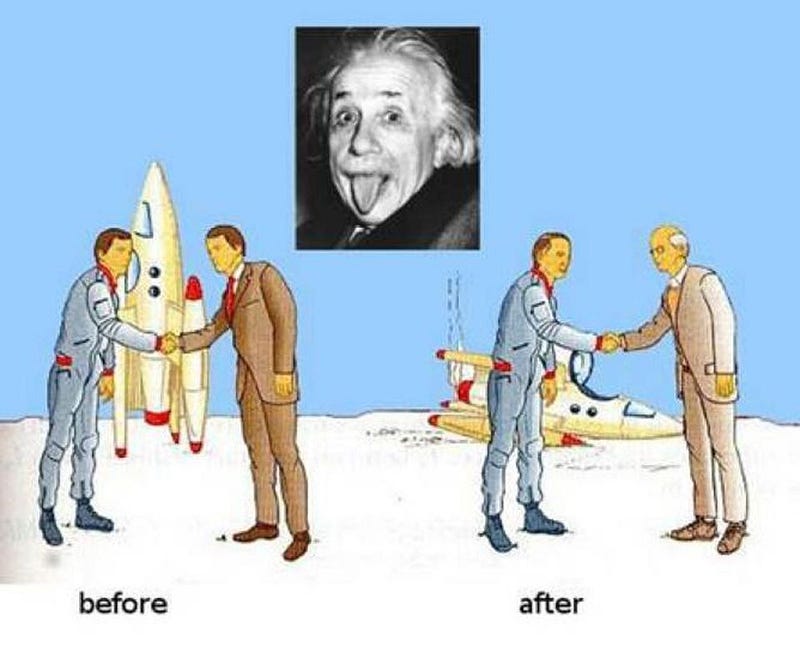

This is why the famous twin paradox works the way it does: someone leaving Earth and traveling close to the speed of light will age less than their identical twin who remains on Earth. The one who moves through space at a greater speed will experience a slower motion through time. If we begin considering General Relativity, where we include the effects of gravity, being deep in a strong gravitational field will have a similar effect on you: time will pass at what seems to be a normal rate for you, but far away from your location, everyone else will age much faster. This reaches its extreme near the singularity of a black hole, after you’ve fallen in past the event horizon.

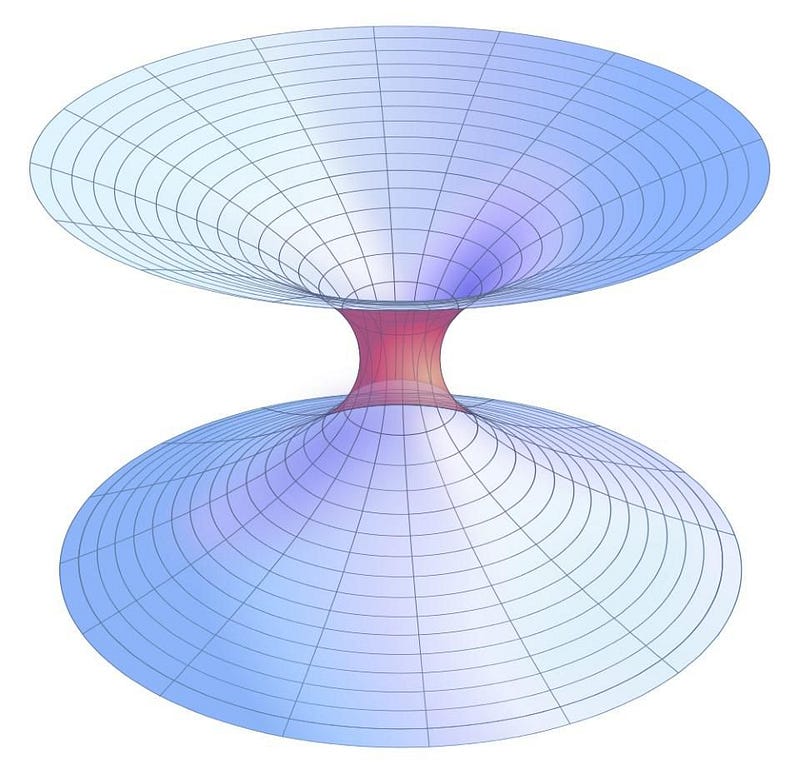

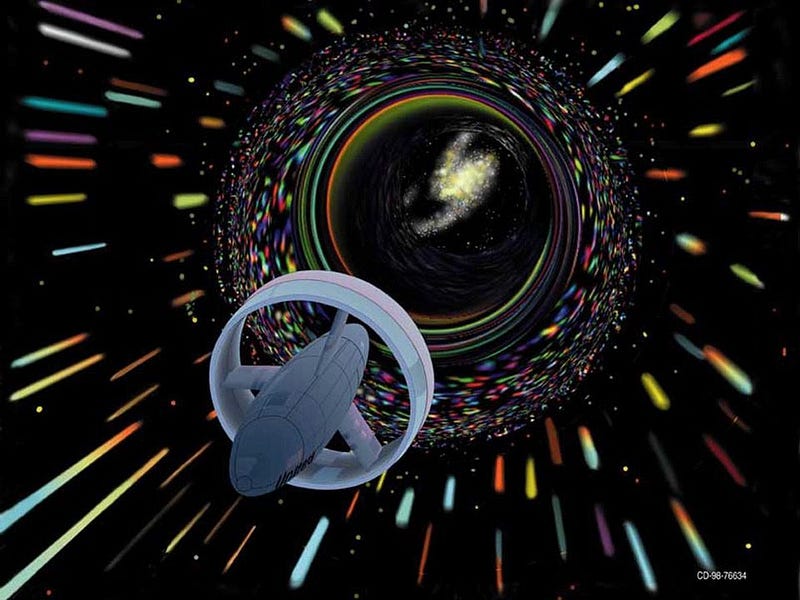

But in General Relativity, there’s another fascinating possibility that arises: that of a wormhole. Wormholes are most commonly thought of as short-cuts through space, but there’s no reason that these shortcuts need to be through space alone; spacetime is just as good! You can use one, if you can create, stabilize, and travel (or send information) through one, to go back or forwards in time by an arbitrary amount. You can even create loops, or closed-timelike-curves, as robust mathematical solutions under the right conditions.

For example, there is a way, in the context of General Relativity, to travel back in time to a specific location; it just requires a little bit of setup.

If you create a massive black hole out of matter, alongside another black hole out of negative mass (which we must theoretically assume exists), you can create a wormhole between the two. Separate them by as far as you want, and accelerate one end of the wormhole close to the speed of light. As long as you’re traveling with that accelerated end, you can step through it whenever you want, and arrive at the other end of the wormhole unscathed. The best part? Because you’ve been traveling close to the speed of light, time has passed differently for you. When you step back through the wormhole, it will be as though virtually no time has passed back at home. You could travel for hundreds of years, and then return to your departure point just seconds after you left. In that sense, traveling back in time could really, physically happen.

There’s a lot that’s possible, and there are plenty of movies that have taken advantage of the combination of a time machine and imaginative storytelling. Of course, there are also plenty of movies that skimp on the science in this regard.

No one remembers Timecop, Hot Tub Time Machine, or Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure for their incredibly accurate portrayals of time travel or a time machine. Idiocracy involves time travel only in the sense that time passes, even while inanimate objects (or people) remain inanimate. (Although, at least the “Time Masheen” is accurate.) Superman rewinds time to save Lois Lane’s life in the original Superman movie, but that’s due to superpowers, not science. Ditto for the recent Doctor Strange movie, or the cult classic Warlock, or Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban; using magic as the mechanism for time travel isn’t going to score you very many science points. In a great many films, time travel is more of a plot device than anything resembling scientific accuracy. Even Army of Darkness, fun though it is, doesn’t have a viable mechanism for the time travel it invokes.

But some films, even though they don’t talk about or depict the mechanism of time travel in any detail, do admirably succeed in describing how time travel would actually work. Traveling forward is easy: you go close to the speed of light, you return to your departure point, and now you’re far in the future. This is how Planet of the Apes sent a human far into the future on a dystopian Earth, and why Star Wars is so dissatisfying when they engage the hyperdrive. Going fast has real consequences for the passage of time, bringing you into the future no matter what else you do.

Going back in time, particularly to a fixed location in the past, is a staple of time travel movies. There are two theories about how this works:

- The timeline is fixed; all that happens is written already, and when you travel back in time, you cannot change the course of events. Your time travel is already written into the timeline.

- The timeline is malleable; the changes you make by going back in time will lead to a different future, perhaps even negating your own existence.

Two great examples of the first theory are Twelve Monkeys and Looper, where the future is already written. Traveling back in time allows you to live and interact with the past, but it doesn’t change the course of history. The events that unfolded to cause you to go back in time have already occurred. You’re simply living out your life, knowing full well what the world’s destiny is.

On the other hand, there’s the possibility that your future isn’t written, even if you yourself came from the future. The Back to the Future franchise and the Terminator/Terminator 2 movies are very sensitive to this. Even though they’re light on the details of how time travel physically works, save for a few key component ingredients, the actions that the time-travelers take can alter their future. Kyle Reese/Sarah Connor can avoid or delay judgment day, battling a terminator sent back to murder (or prevent the existence of) the boy that will battle the rise of the machines. Marty McFly travels through time to save his friend’s life, but has to ensure he doesn’t prevent his own existence in the process. These are two of the best examples of a time travel movie where the future is alterable. The 2009 Star Trek, Star Trek: First Contact, and Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home all play with this as well, to great effect.

There are two movies that stand out for scientific accuracy in time travel while including a great level of detail: Interstellar and Contact. Both movies, ironically, consulted with the same scientist, Kip Thorne, and both take advantage of the black hole/wormhole idea. Deep in the gravitational field of a black hole in Interstellar, time passes at a different rate, leading to a relativistic twist late in the movie. In Contact, a seeming instant on Earth coincided with a nearly-day-long excursion across the galaxy and, potentially the Universe. The physics of wormholes, black holes, and General Relativity is on full display in these films, and in spectacular fashion no less.

Finally, there’s perhaps the most realistic and interesting movie to make use of time travel in the “time loop” sense: Groundhog Day. Any solution in General Relativity that admits closed-timelike-curves is usually rejected because of philosophical concerns like the Grandfather Paradox, but these mathematical solutions are internally self-consistent and could describe reality, particularly if we accept that the start of the loop “resets” with every iteration. Groundhog Day makes phenomenal use of this, and the time loop is only broken when sufficient changes are made in this humorous, ethical tale of kindness and self-discovery. Although it, too, is short on the science, its depiction of a time loop is second to none. (Although I have not seen Edge Of Tomorrow.)

And those are the movies (that I’ve seen) that deal with time travel that get the science right!

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.