Ask Ethan: When Were Dark Matter And Dark Energy Created?

They make up 95% of our Universe today, but they weren’t always so important.

One of the most puzzling mysteries about the Universe is simply, “where is everything?” All that we can see, find, or interact with is made up of particles from the Standard Model, including photons, neutrinos, electrons, and the quarks and gluons which comprise the building blocks of our atoms. Yet when we look out at the cosmic ocean, we find that all of this makes up just under 5% of the total energy in the Universe; the rest is unseen. We call the missing components dark energy (68%) and dark matter (27%), but we don’t know what they are. Do we even know when they came into existence? That’s what Alon David wants to know, asking:

Today [normal matter] is only 4.9% while Dark Matter and Dark Energy takes the rest. Where did they come from?

Let’s find out.

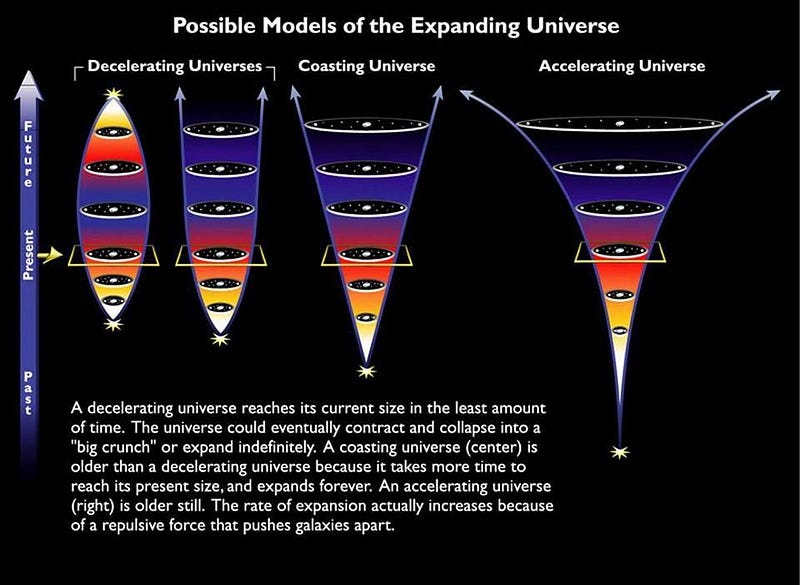

There’s so much that we don’t know about dark matter and dark energy, but there are a great many things that we can definitively say about them. We’ve observed that dark energy affects the expansion of the Universe, only becoming prominent and detectable about 6-to-9 billion years ago. It appears to be the same in all directions; it appears to have a constant energy density throughout time; it appears to not clump or cluster or anti-cluster with matter, indicating it’s uniform throughout space. When we look at how the Universe expands, dark energy is absolutely required, with approximately 68% of the total energy of the Universe presently existing in the form of dark energy.

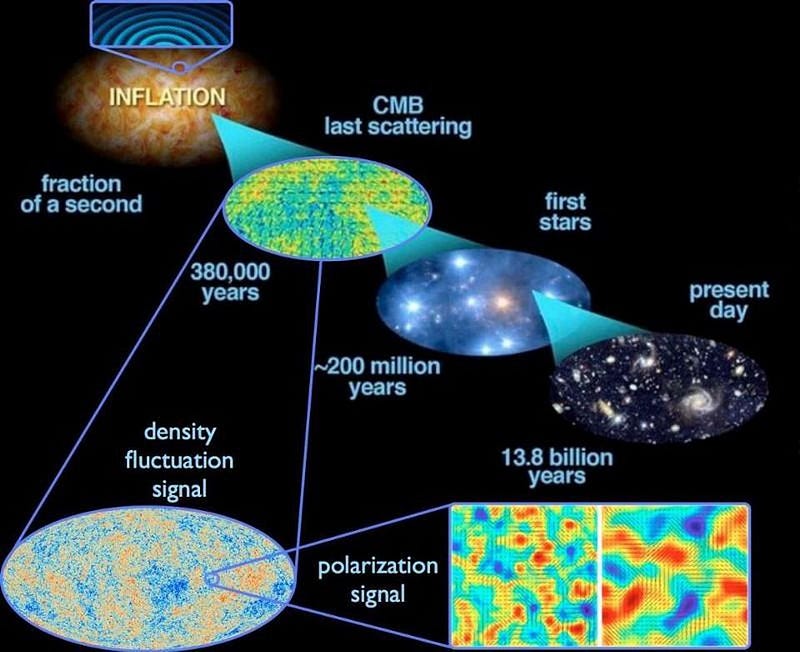

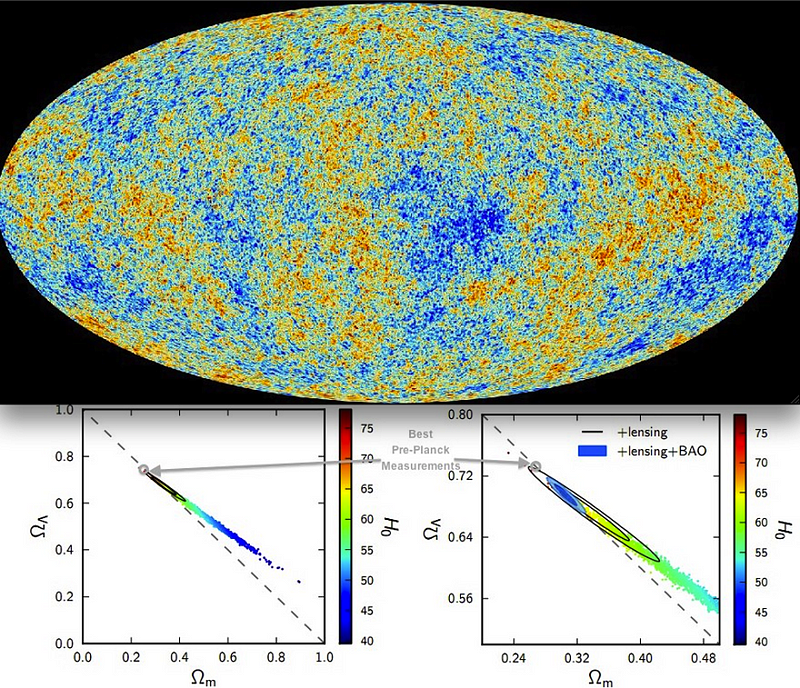

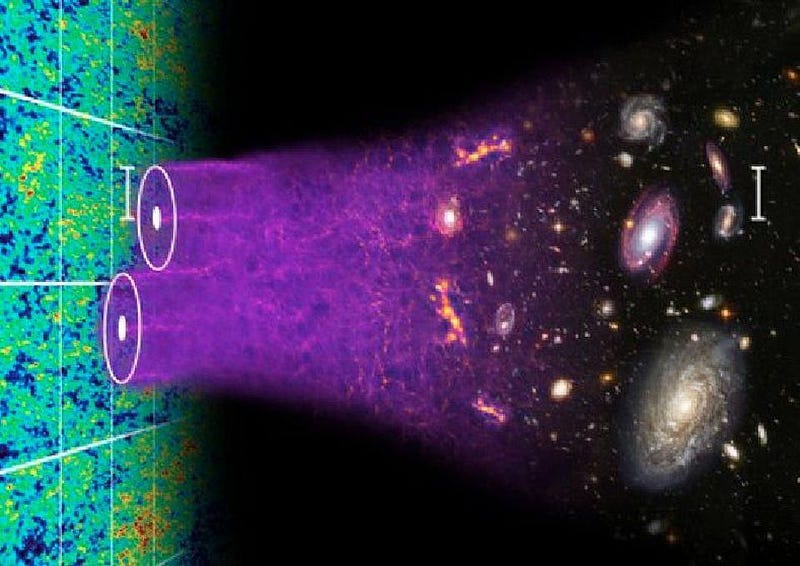

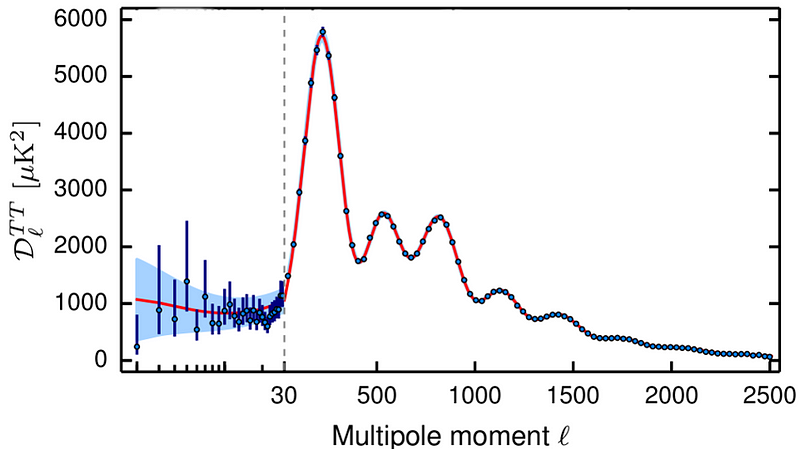

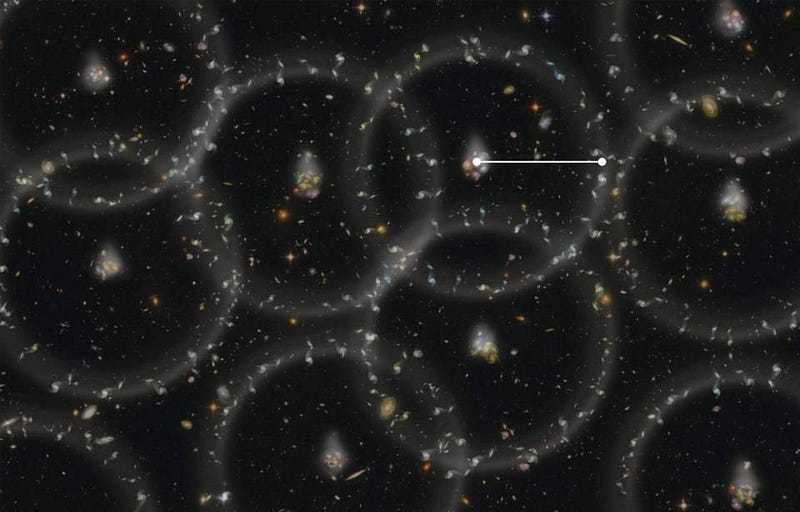

Dark matter, on the other hand, has shown its effects for the entire 13.8 billion year history of our Universe. The great cosmic web of structure, from the earliest times to the present day, requires that dark matter exist in about five times the abundance of normal matter. Dark matter does clump and cluster, and its effects can be seen in the formation of the earliest quasars, galaxies, and clouds of gas. Even prior to that, dark matter’s gravitational effects show up in the earliest light from the Universe: the cosmic microwave background, or the leftover glow from the Big Bang. The pattern of imperfections requires that the Universe be made of about 27% dark matter, in comparison to only 5% normal matter. Without it, all that we observe would be impossible to explain.

But does this necessarily mean that dark matter and dark energy were created back at the moment of the Big Bang? Or are there other possibilities? The difficult thing about the Universe is that we can only see the parts of it that are accessible to us today. When an effect is too small to be seen — such as when other effects are more important — we can only draw inferences, not solid conclusions.

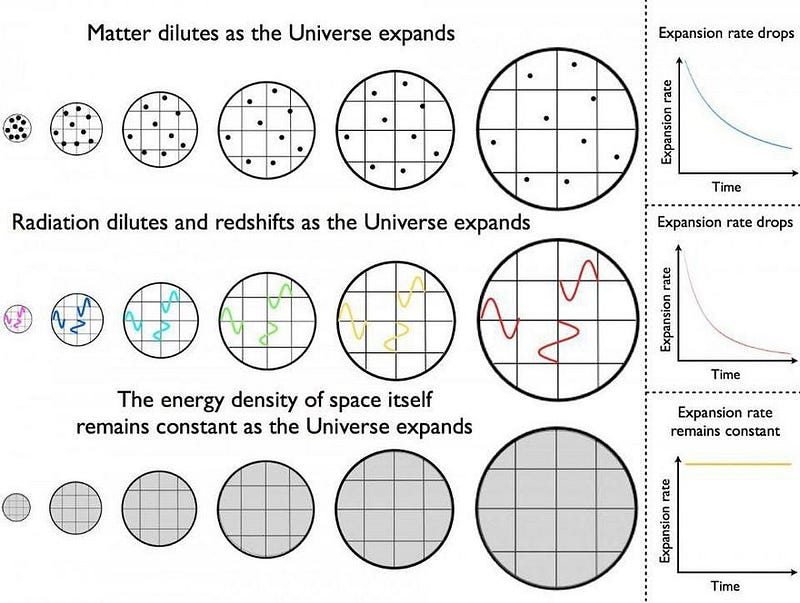

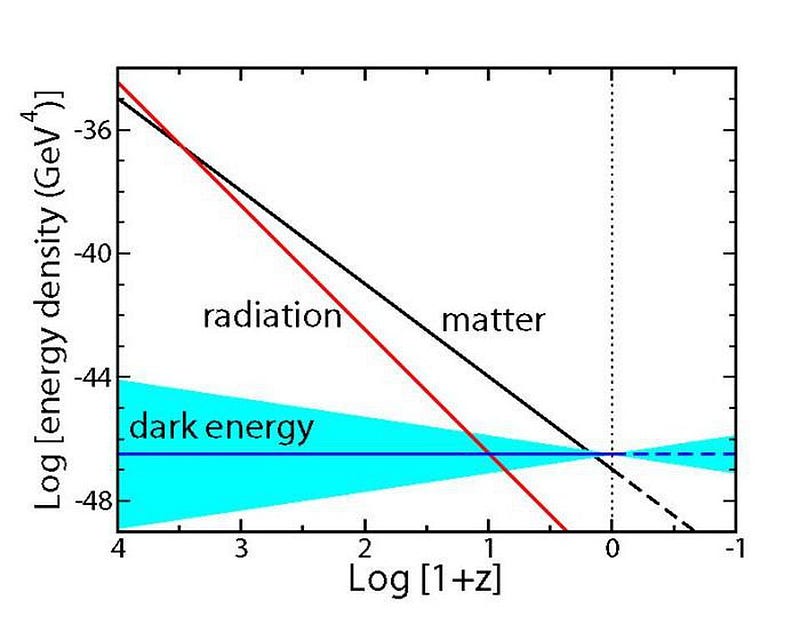

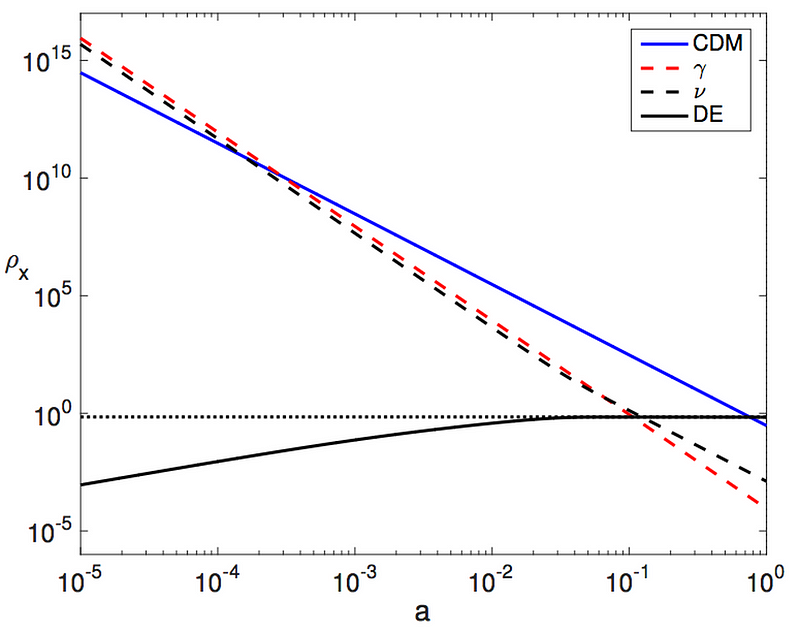

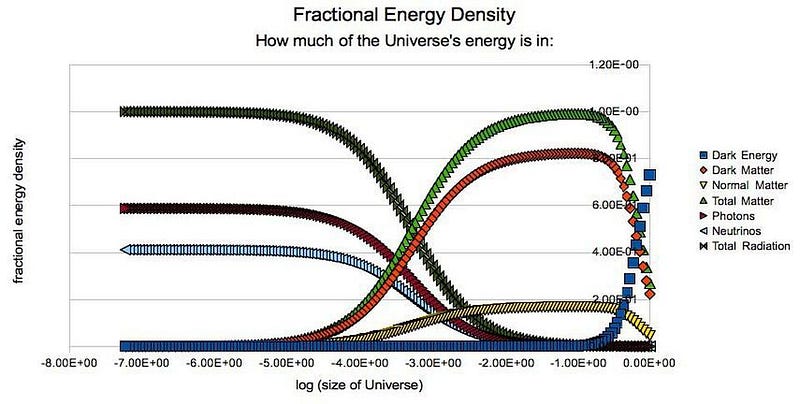

This is particularly problematic for dark energy. As the Universe expands, it dilutes; the volume increases while the total number of particles within it stays the same. The matter density (both normal and dark) goes down; the radiation density goes down even faster (since the number of particles not only drops, but the energy-per-photon drops due to redshifting); but the dark energy density remains constant.

Our Universe may be dark energy-dominated today, but this is a relatively recent happenstance. In the past, the Universe was smaller and denser, meaning the matter (and radiation) densities were much higher. About 6 billion years ago, the matter and dark energy densities were equal; about 9 billion years ago, the dark energy density is low enough that its effects on the Universe’s expansion rate were not noticeable. The farther we extrapolate back in time (or size/scale of the Universe), the more difficult it becomes to see and measure dark energy’s effects.

To the best of our ability, it appears that dark energy has an absolutely constant energy density. We can use the data we have to constrain the dark energy equation of state, which we parameterize by a quantity known as w. If dark energy is exactly a cosmological constant, then w = -1, exactly, and does not change over time. We have used the full suite of cosmological data we have — from large-scale structure, from the cosmic microwave background, from objects at great cosmic distances — to constrain w as best as possible. The most stringent constraints come from baryon acoustic oscillations, and tell us that w = -1.00 ± 0.08, with future observatories like LSST and WFIRST poised to get those uncertainties down to about 1%.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that dark energy has always existed with a constant energy density, however. It could change over time, so long as it changes within the observational constraints. There could be a connection between dark energy and the initial, pre-Big Bang expansion of the Universe known as cosmic inflation, which is the idea behind quintessence fields. Or dark energy could be an effect which didn’t exist in the earliest stages of the Universe, and only manifested itself at late times.

We have no evidence that speaks one way or the other on dark energy’s presence or absence for the first 4 billion years or so of the Universe’s history. We have good reasons to presume it hasn’t changed, but not the observational certainty to back it up.

Dark matter, on the other hand, must have existed from very early times. The pattern of fluctuations we see in the CMB is the earliest evidence we have for dark matter in our Universe, dating from approximately 380,000 years after the Big Bang. Yet already imprinted in the pattern of peaks-and-valleys in the angular scale fluctuations is overwhelming evidence for dark matter, in that critical 5-to-1 ratio with normal matter. Dark matter has not only been providing the seeds of structure, which causes more and more dark matter to fall into the overdense regions (and be lost from the underdense regions), but has been doing so since the earliest stages in the Universe.

This doesn’t necessarily mean, however, that dark matter was present at the instant of the hot Big Bang, though. Dark matter could have been created from the very moment inflation ended; it could have been created from high-energy interactions that took place immediate afterwards; it could have arisen from high-energy particles up at the GUT scale; it could have arisen from a broken symmetry (such as a Peccei-Quinn-like symmetry) slightly later; it could have come about from right-handed Dirac neutrinos when they gained ultra-heavy masses from a cosmic see-saw mechanism; they could have remained massless until the electroweak symmetry broke, which could be connected to dark matter.

Without knowing exactly what dark matter is — including whether or not it’s a particle at all — we cannot state with any certainty exactly when it may have arisen. But from the measurements of the large-scale structure of the Universe, including the signatures imprinted in the earliest picture of all, we can be absolutely certain that dark matter arose in the very early stages of the Big Bang, and possibly at the very beginning of it all. Dark energy may have been around the whole time, or it may have only emerged much later; there is substantial exploration of the idea that only when complex structure forms, dark energy arises and becomes important in the Universe.

Part of the great challenge for modern cosmology is to uncover the nature of these missing components of the Universe. If we can do exactly that, we’ll begin to understand when and how dark matter and dark energy arose. What we can say for certain is that, in the very early stages, radiation was the dominant component of the Universe, with tiny amounts of normal matter always present. Dark matter may have arisen at the very beginning, or it may have arisen slightly later, but still very early on. Dark energy is presently thought to have always been there, but only became important and detectable when the Universe was already billions of years old. Determining the rest is a task for our scientific future.

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.