Ask Ethan: What does the edge of the Universe look like?

There’s a point beyond which we cannot go, there are things beyond that we cannot know. But here’s what we expect.

“The Edge… there is no honest way to explain it because the only people who really know where it is are the ones who have gone over.”

–Hunter S. Thompson

13.8 billion years ago, the Universe as we know it began with the hot Big Bang. Over that time, space itself has expanded, the matter has undergone gravitational attraction, and the result is the Universe we see today. But as vast as it all is, there’s a limit to what we can see. Beyond a certain distance, the galaxies disappear, the stars twinkle out, and no signals from the distant Universe can be seen. What lies beyond that? That’s this week’s question from Dan Newman, who asks:

If the universe is finite in volume, then is there a boundary? Is it approachable? And what might the view in that direction be?

Let’s start by starting at our present location, and looking out as far into the distance as we can.

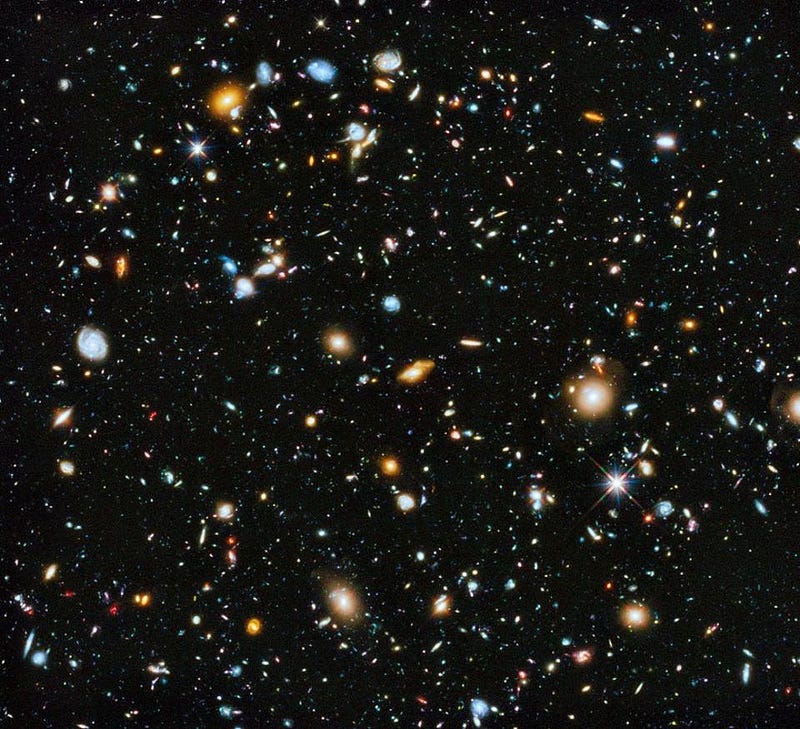

In our own backyard, the Universe is full of stars. But go more than about 100,000 light years away, and you’ve left the Milky Way behind. Beyond that, there’s a sea of galaxies: perhaps two trillion in total contained in our observable Universe. They come in a great diversity of types, shapes, sizes and masses. But as you look back to the more distant ones, you start to find something unusual: the farther away a galaxy is, the more likely it is to be smaller, lower in mass, and to have its stars be intrinsically bluer in color than the nearby ones.

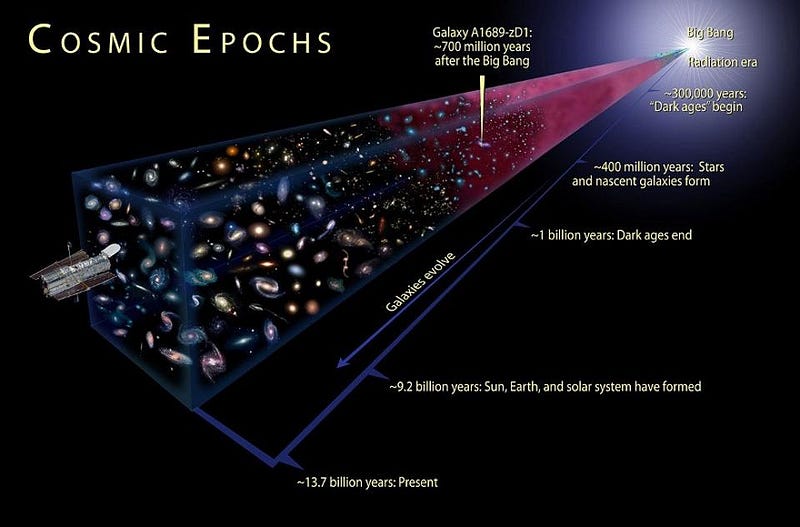

This makes sense in the context of a Universe that had a beginning: a birthday. That’s what the Big Bang was, the day that the Universe as we know it was born. For a galaxy that’s relatively close by, it’s just about the same age that we are. But when we look at a galaxy that’s billions of light years away, that light has needed to travel for billions of years to reach our eyes. A galaxy whose light takes 13 billion years to reach us must be less than one billion years old, and so the farther away we look, we’re basically looking back in time.

The above image is the Hubble eXtreme Deep Field (XDF), the deepest image of the distant Universe ever taken. There are thousands of galaxies in this image, at a huge variety of distances from us and from one another. What you can’t see in simple color, though, is that each galaxy has a spectrum associated with it, where clouds of gas absorb light at very particular wavelengths, based on the simple physics of the atom. As the Universe expands, that wavelength stretches, so the more distant galaxies appear redder than they otherwise would. That physics allows us to infer their distance, and lo and behold, when we assign distances to them, the farthest galaxies are the youngest and smallest ones of all.

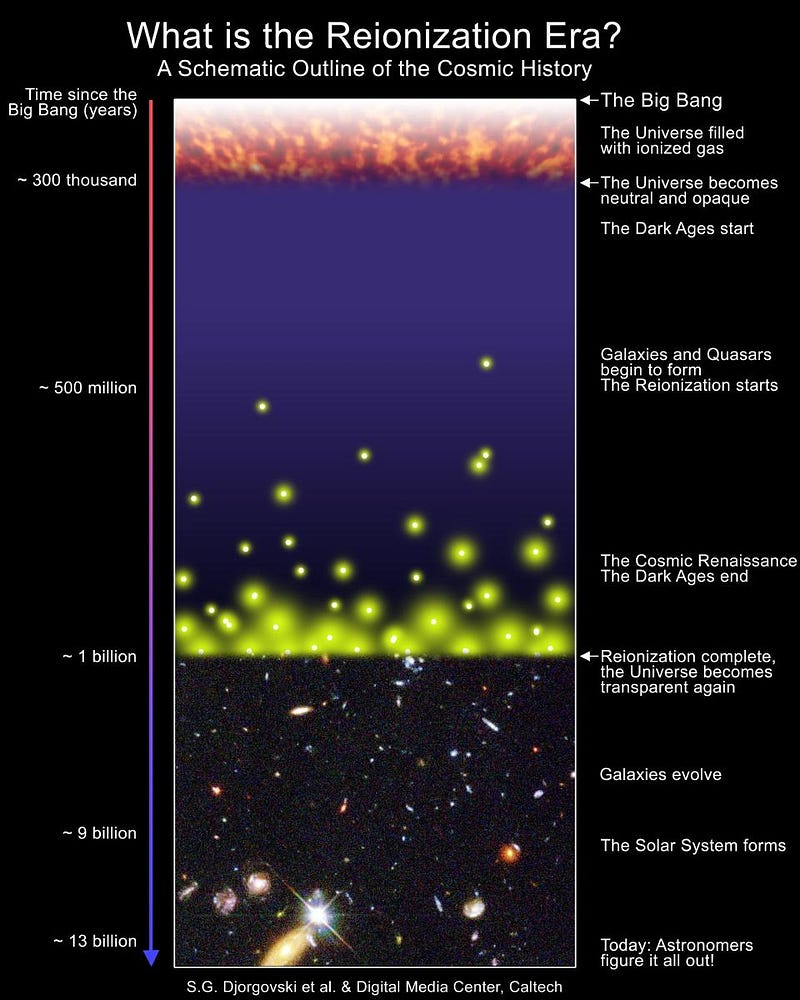

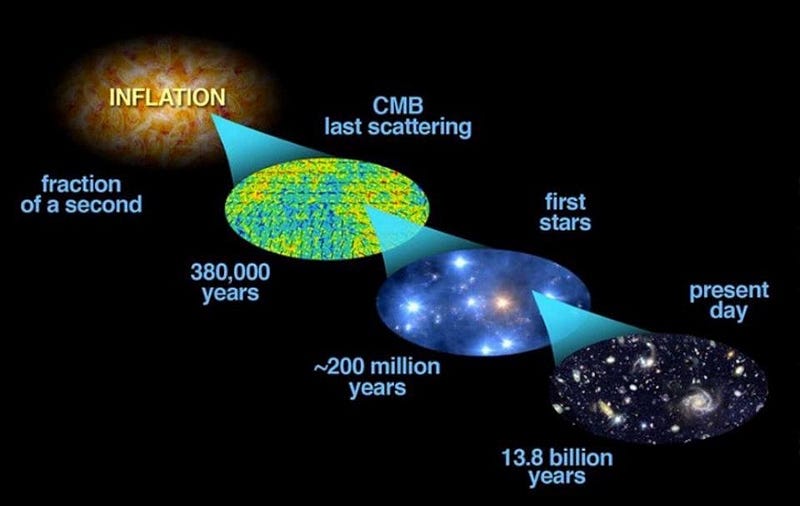

Beyond the galaxies, we expect there to be the first stars, and then nothing but neutral gas, when the Universe hadn’t had enough time to pull matter into dense enough states to form a star yet. Going back additional millions of years, the radiation in the Universe was so hot that neutral atoms couldn’t form, meaning that photons bounced off of charged particles continuously. When neutral atoms did form, that light should simply stream in a straight line forever, unaffected by anything other than the expansion of the Universe. The discovery of this leftover glow — the Cosmic Microwave Background — more than 50 years ago was the ultimate confirmation of the Big Bang.

So from where we are today, we can look out in any direction we like and see the same cosmic story unfolding. Today, 13.8 billion years after the Big Bang, we have the stars and galaxies we know today. Earlier, galaxies were smaller, bluer, younger and less evolved. Before that, there were the first stars, and prior to that, just neutral atoms. Before neutral atoms, there was an ionized plasma, then even earlier there were free protons and neutrons, spontaneous creation of matter-and-antimatter, free quarks and gluons, all the unstable particles in the Standard Model, and finally the moment of the Big Bang itself. Looking to greater and greater distances is equivalent to looking all the way back in time.

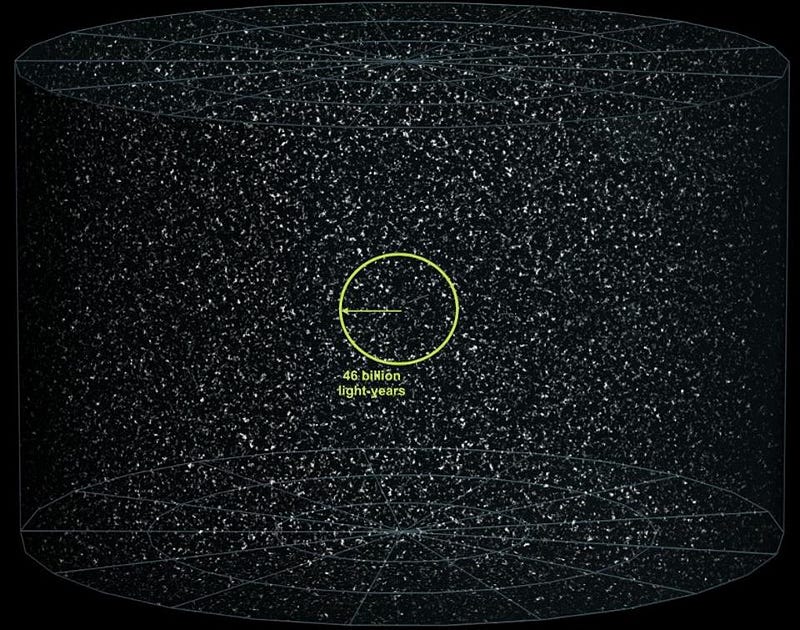

Although this defines our observable Universe — with the theoretical boundary of the Big Bang located 46.1 billion light years from our current position — this is not a real boundary in space. Instead, it’s simply a boundary in time; there’s a limit to what we can see because the speed of light allows information to only travel so far over the 13.8 billion years since the hot Big Bang. That distance is farther than 13.8 billion light years because the fabric of the Universe has expanded (and continues to expand), but it’s still limited. But what about prior to the Big Bang? What would you see if you somehow went to the time just a tiny fraction of a second earlier than when the Universe was at its highest energies, hot and dense, and full of matter, antimatter and radiation?

You’d find that there was a state called cosmic inflation: where the Universe was expanding ultra fast, and dominated by energy inherent to space itself. Space expanded exponentially during this time, where it was stretched flat, where it was given the same properties everywhere, where pre-existing particles were all pushed away, and where fluctuations in the quantum fields inherent to space were stretched across the Universe. When inflation ended where we are, the hot Big Bang filled the Universe with matter and radiation, giving rise to the part of the Universe — the observable Universe — that we see today. 13.8 billion years later, here we are.

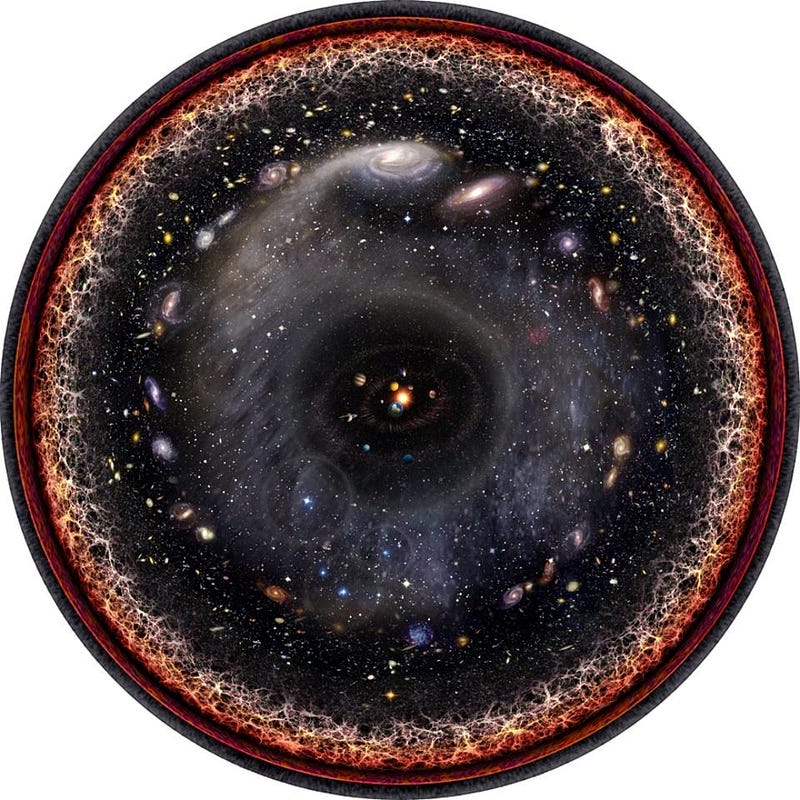

The thing is, there’s nothing special about our location, neither in space nor in time. The fact that we can see 46 billion light years away doesn’t make that boundary or that location anything special; it simply marks the limit of what we can see. If we could somehow take a “snapshot” of the entire Universe, going way beyond the observable part, as it exists 13.8 billion years after the Big Bang everywhere, it would all look like our nearby Universe does today. There would be a great cosmic web of galaxies, clusters, filaments, and cosmic voids, extending far beyond the comparatively small region we can see. Any observer, at any location, would see a Universe that was very much like the one we see from our own perspective.

The individual details would be different, just as the details of our own solar system, galaxy, local group, and so on, are different from any other observer’s viewpoint. But the Universe itself isn’t finite in volume; it’s only the observable part that’s finite. The reason for that is that there’s a boundary in time — the Big Bang — that separates us from the rest. We can approach that boundary only through telescopes (which look to earlier times in the Universe) and through theory. Until we figure out how to circumvent the forward flow of time, that will be our only approach to better understand the “edge” of the Universe. But in space? There’s no edge at all. To the best that we can tell, someone at the edge of what we see would simply see us as the edge instead!

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.