Ask Ethan: How Large Is The Entire, Unobservable Universe?

If we know how big the observable Universe is, why can’t we figure out how big the unobservable part is?

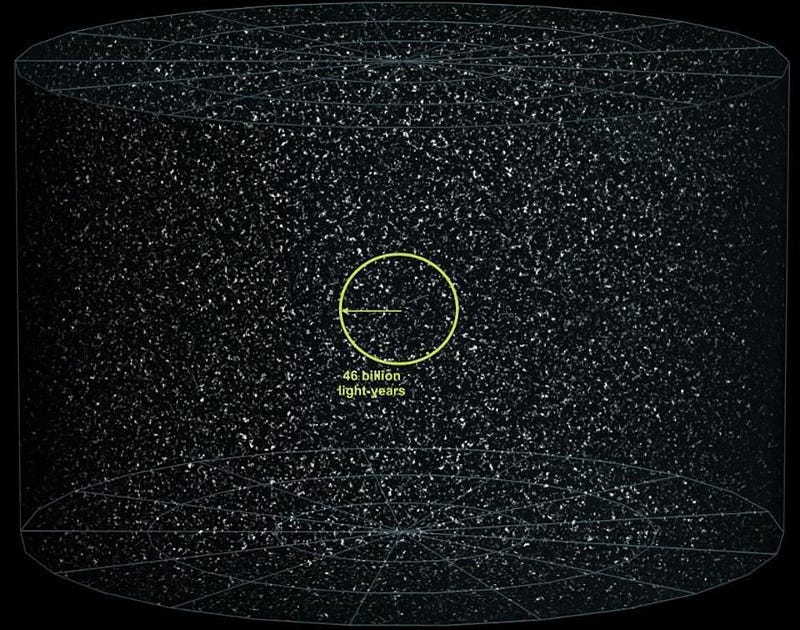

13.8 billion years ago, the Big Bang occurred. The Universe was filled with matter, antimatter, radiation, and existed in an ultra-hot, ultra-dense, but expanding-and-cooling state. By today, the volume containing our observable Universe has expanded to be 46 billion light years in radius, with the light that’s first arriving at our eyes today corresponding to the limit of what we can measure. But what lies beyond? What about the unobservable Universe? That’s what Gray Bryan wants to know, as he asks:

We know the size of the Observable Universe since we know the age of the Universe (at least since the phase change) and we know that light radiates. […] My question is, I guess, why doesn’t the math involved in making the CMB and other predictions, in effect, tell us the size of the Universe? We know how hot it was and how cool it is now. Does scale not affect these calculations?

Oh, if only it were so easy.

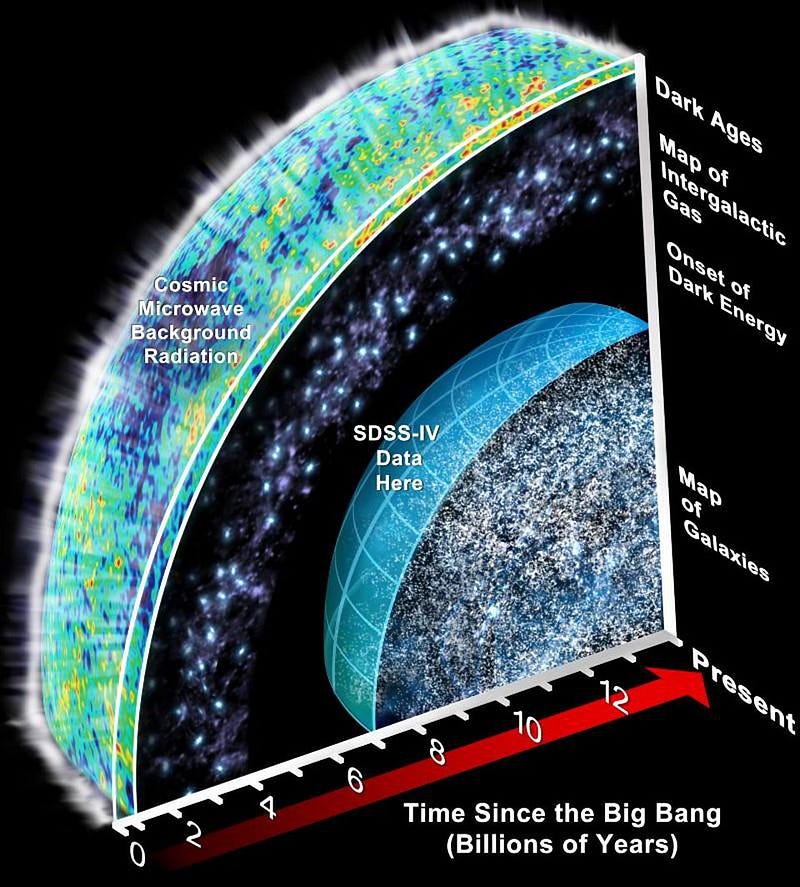

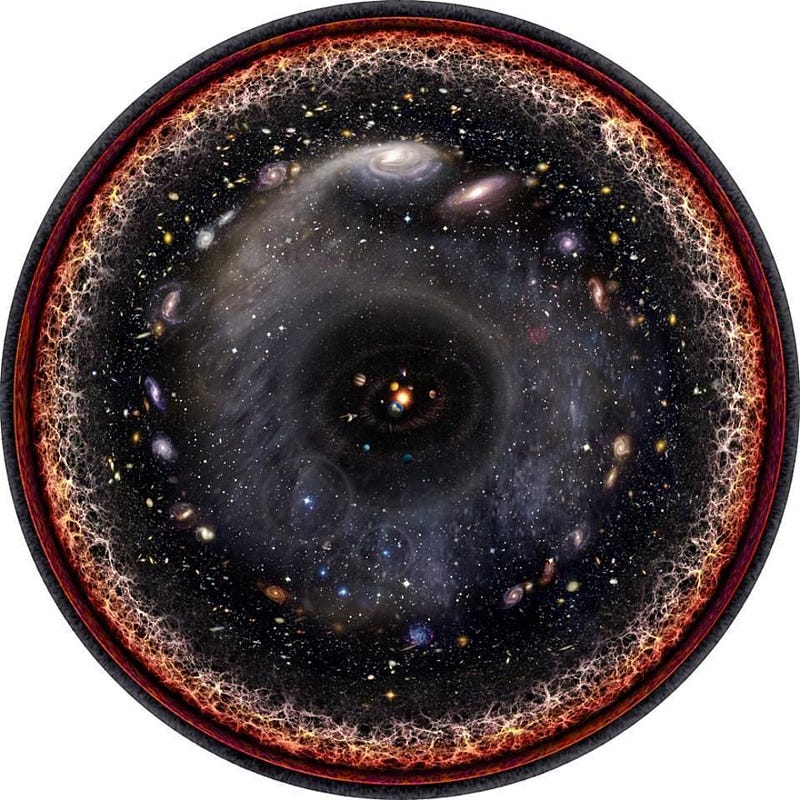

The Universe is cold and clumpy today, but it’s also expanding and gravitating. When we look to greater and greater distances, we see things as they were not only far away, but also back in time, owing to the finite speed of light. The more distant Universe is less clumpy and more uniform, having had less time to form larger, more complicated structures that require more time for gravity’s effects to take place.

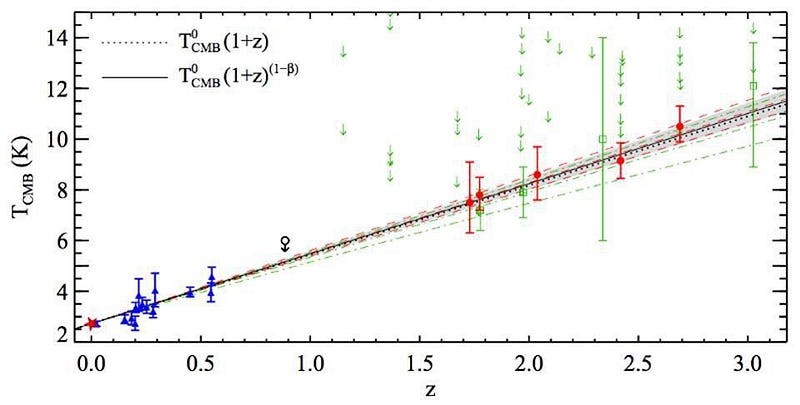

The early, distant Universe was also hotter. The expanding Universe causes all the light that travels through the Universe to stretch in wavelength. As the wavelength stretches, it loses energy, becoming cooler. This means the Universe was hotter in the distant past, a fact we’ve confirmed through observations of distant features in the Universe.

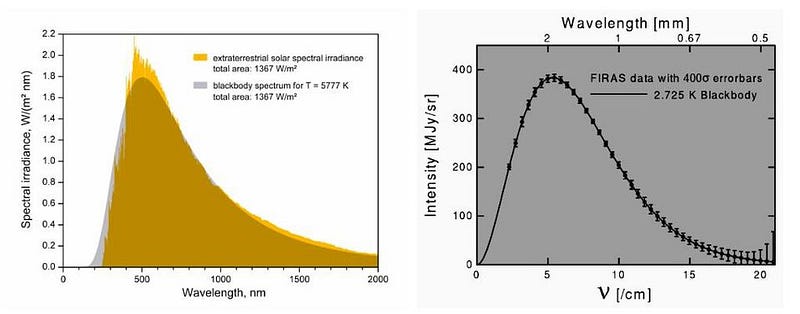

We can measure the temperature of the Universe as it is today, 13.8 billion years after the Big Bang, by looking at the leftover radiation from that hot, dense, early state. Today, this shows up in the microwave portion of the spectrum, and is known as the Cosmic Microwave Background. Coming in with a blackbody spectrum and a temperature of 2.725 K, it’s easy to confirm that these observations match, with an incredible precision, the predictions that arise from the Big Bang model of our Universe.

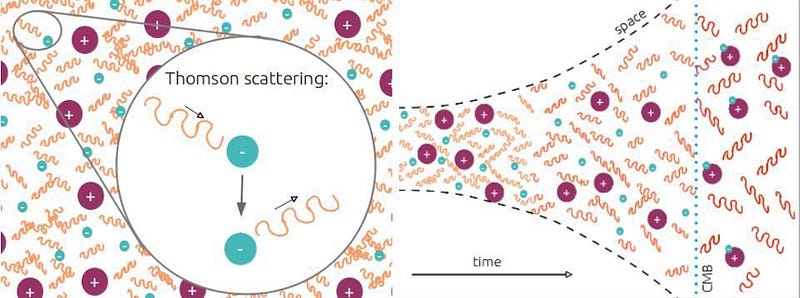

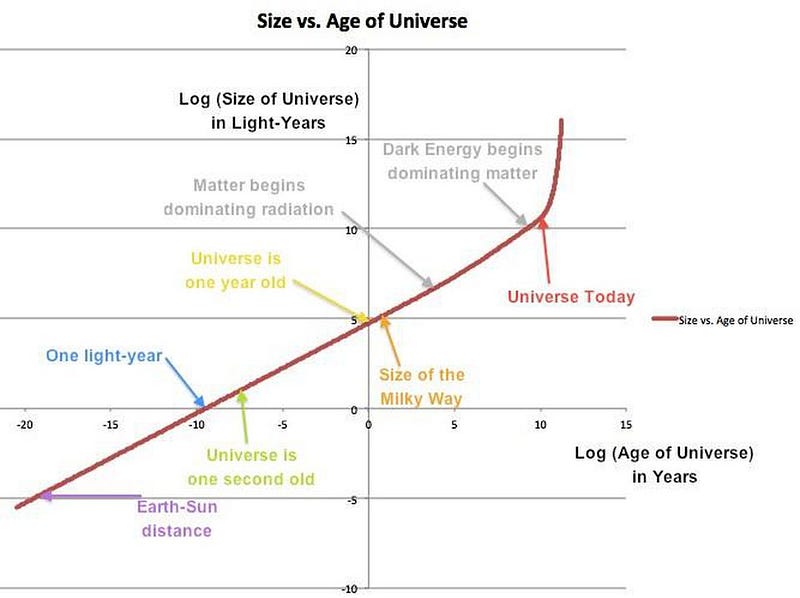

Moreover, we know how this radiation evolves in energy as the Universe expands. A photon’s energy is directly proportional to the inverse of its wavelength. When the Universe was half its size, the photons from the Big Bang had double the energy, while when the Universe was 10% of its current size, those photons had ten times the energy. If we’re willing to go back to when the Universe was just 0.092% its present size, we’ll find a Universe that’s 1089 times hotter than it is today: around 3000 K. At these temperatures, the Universe is hot enough to ionize all the atoms in it. Instead of solid, liquid, or gas, all the matter in the entire Universe was in the form of an ionized plasma.

The way we arrive at the size of the Universe today is through understanding three things in tandem:

- How quickly the Universe is expanding today, something we can measure via a number of methods,

- How hot the Universe is today, which we know from looking at the radiation of the Cosmic Microwave Background,

- and what the Universe is made out of, including matter, radiation, neutrinos, antimatter, dark matter, dark energy, and more.

By taking the Universe we have today, we can extrapolate back to the earliest stages of the hot Big Bang, and arrive at a figure for both the age and the size of the Universe together.

From the full suite of observations available, including the cosmic microwave background but also including supernova data, large-scale structure surveys, and baryon acoustic oscillations, among others, we get our Universe. 13.8 billion years after the Big Bang, it’s now 46.1 billion light years in radius. That’s the limit of what’s observable. Any farther than that, and even something moving at the speed of light since the moment of the hot Big Bang will not have had sufficient time to reach us. As time goes on, the age and the size of the Universe will increase, but there will always be a limit to what we can observe.

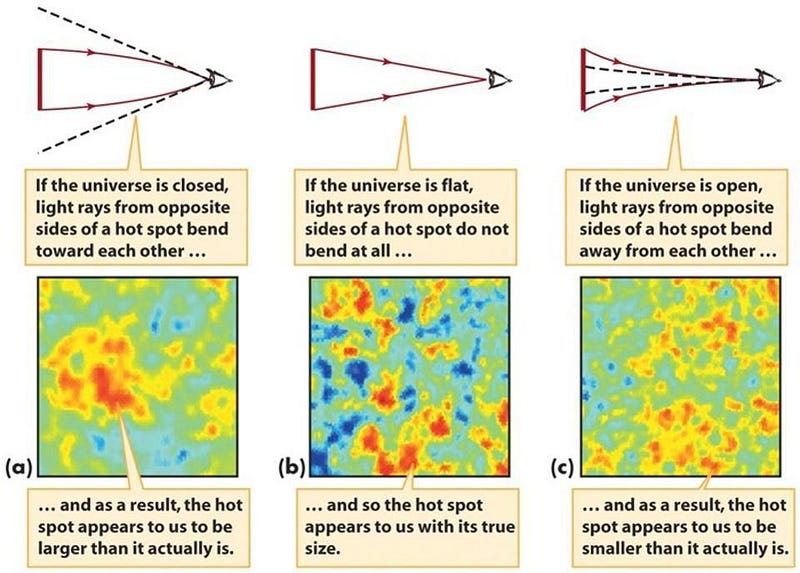

So what can we say about the part of the Universe that’s beyond the limits of our observations? We can only make inferences based on the laws of physics as we know them, and the things we can measure within our observable Universe. For example, we observe that the Universe is spatially flat on the largest scales: it’s neither positively nor negatively curved, to a precision of 0.25%. If we assume that our current laws of physics are correct, we can set limits on how large, at least, the Universe must be before it curves back on itself.

Observations from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and the Planck satellite are where we get the best data. They tell us that if the Universe does curve back in on itself and close, the part we can see is so indistinguishable from “uncurved” that it much be at least 250 times the radius of the observable part.

This means the unobservable Universe, assuming there’s no topological weirdness, must be at least 23 trillion light years in diameter, and contain a volume of space that’s over 15 million times as large as the volume we can observe. If we’re willing to speculate, however, we can argue quite compellingly that the unobservable Universe should be significantly even bigger than that.

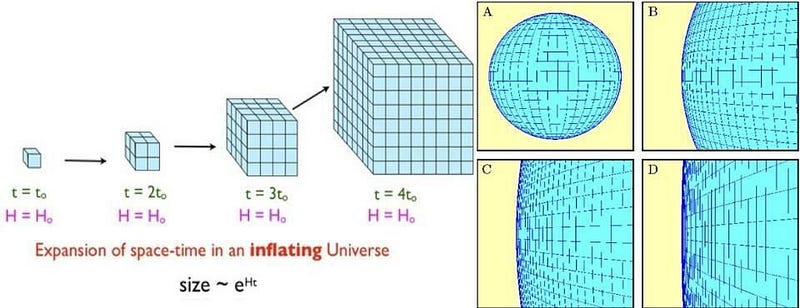

The hot Big Bang might mark the beginning of the observable Universe as we know it, but it doesn’t mark the birth of space and time itself. Before the Big Bang, the Universe underwent a period of cosmic inflation. Instead of being filled with matter and radiation, and instead of being hot, the Universe was:

- filled with energy inherent to space itself,

- expanding at a constant, exponential rate,

- and creating new space so quickly that the smallest physical length scale, the Planck length, would be stretched to the size of the presently observable Universe every 10–32 seconds.

It’s true that in our region of the Universe, inflation came to an end. But there are three questions we don’t know the answer to that have a tremendous influence on how big the Universe truly is, and whether it’s infinite or not.

- How big was the region of the Universe, post-inflation, that created our hot Big Bang?

- Is the idea of “eternal inflation,” where the Universe inflates eternally into the future in at least some regions, correct?

- And, finally, how long did inflation go on prior to its end and the resultant hot Big Bang?

It’s possible that the Universe, where inflation occurred, barely attained a size larger than what we can observe. It’s possible that, any year now, the evidence for an “edge” to where inflation happened will materialize. But it’s also possible that the Universe is googols of times larger than what we can observe. Until we can answer these questions, we may never know.

Beyond what we can see, we strongly suspect that there’s plenty more Universe out there just like ours, with the same laws of physics, the same types of physical, cosmic structures, and the same chances at complex life. There should also be a finite size and scale to the “bubble” in which inflation ended, and an exponentially huge number of such bubbles contained within the larger, inflating spacetime. But as inconceivably large as that entire Universe — or Multiverse, if you prefer — may be, it might not be infinite. In fact, unless inflation went on for a truly infinite amount of time, or the Universe was born infinitely large, the Universe ought to be finite in extent.

The biggest problem of all, though, is that we don’t have enough information to definitively answer the question. We only know how to access the information available inside our observable Universe: those 46 billion light years in all directions. The answer to the biggest of all questions, of whether the Universe is finite or infinite, might be encoded in the Universe itself, but we can’t access enough of it to know. Until we either figure it out, or come up with a clever scheme to expand what we know physics is capable of, all we’ll have are the possibilities.

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.