Ask Ethan: How close are we to a Theory of Everything?

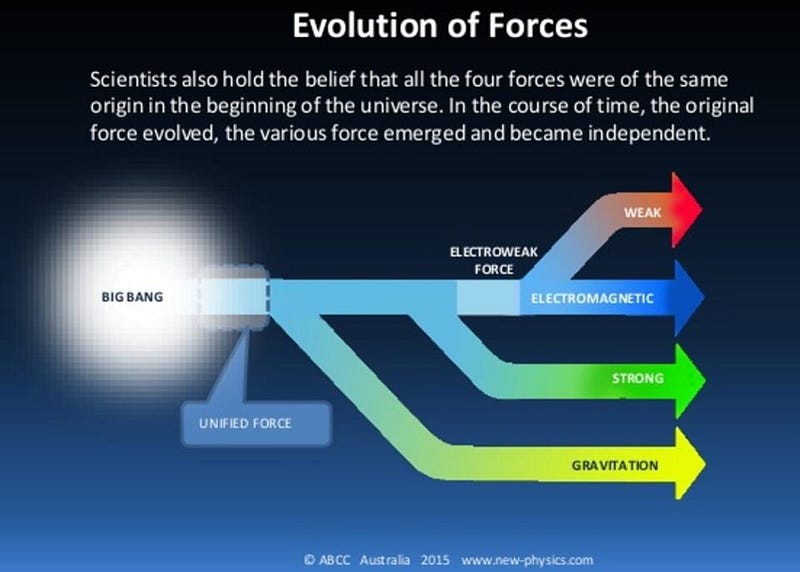

The four fundamental forces might have been just a single, unified one in the very early Universe. Could that be true?

“Those who begin coercive elimination of dissent soon find themselves exterminating dissenters. Compulsory unification of opinion achieves only the unanimity of the graveyard.” –Robert Jackson

Since well before Einstein, it was the dream of those who study the Universe to find a single equation to govern as many phenomena as possible. Rather than have a separate law for each and every physical property the Universe has, we could unify these laws into a single, overarching framework. All the laws of electric charge, magnetism, electric currents, induction and more were unified into a single framework by James Clerk Maxwell in the mid-1800s. Ever since, physicists have dreamed of a Theory of Everything: a single equation governing all the laws of the Universe. What progress have we made? That’s the question of Paul Harding, who wants to know:

Has science made any progress with regards to the Grand Unified Theory and the Theory of Everything? And could you elaborate on what it would mean if we did find a unified equation?

Yes, we’ve made progress, but we’re not there yet. Not only that, but it’s not even a certainty that there even is a theory of everything.

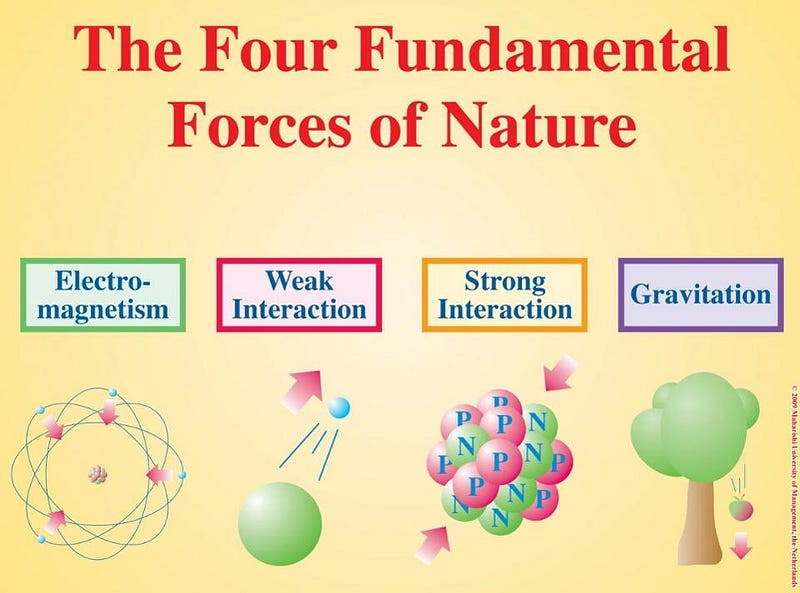

The laws of nature, as we’ve discovered them so far, can be broken down into four fundamental forces: the force of gravity, governed by General Relativity, and the three quantum forces that govern particles and their interactions, the strong nuclear force, the weak nuclear force, and the electromagnetic force. The earliest attempts at a unified theory of everything came shortly after the publication of General Relativity, before we understood that there were fundamental laws to govern nuclear forces. These ideas, known as Kaluza-Klein theories, sought to unify gravitation with electromagnetism.

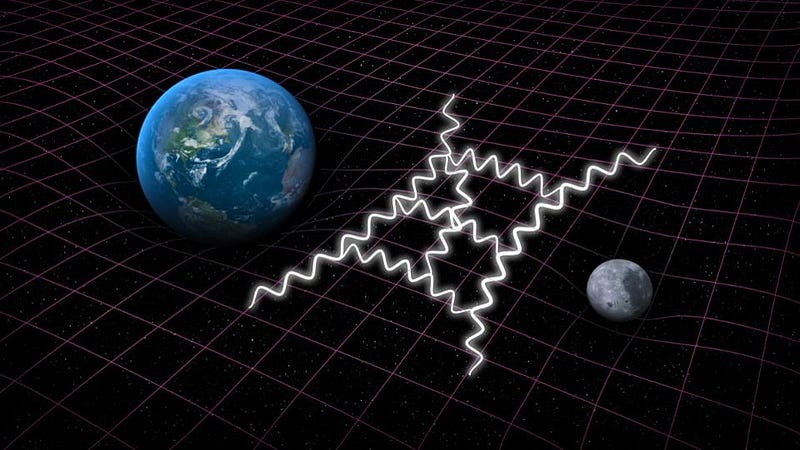

By adding an extra spatial dimension to Einstein’s General Relativity, a fifth dimension overall (in addition to the standard three space and one time) gave rise to Einstein’s gravity, Maxwell’s electromagnetism, and a new, extra scalar field. The extra dimension would need to be small enough to avoid interfering with the laws of gravity, and the details were such that the extra scalar field needed to have no discernible effects on the Universe. Since there was no way to formulate a quantum theory of gravity with this, the discovery of quantum physics and the nuclear forces — which this attempt at unification couldn’t account for — caused this to fall out of favor.

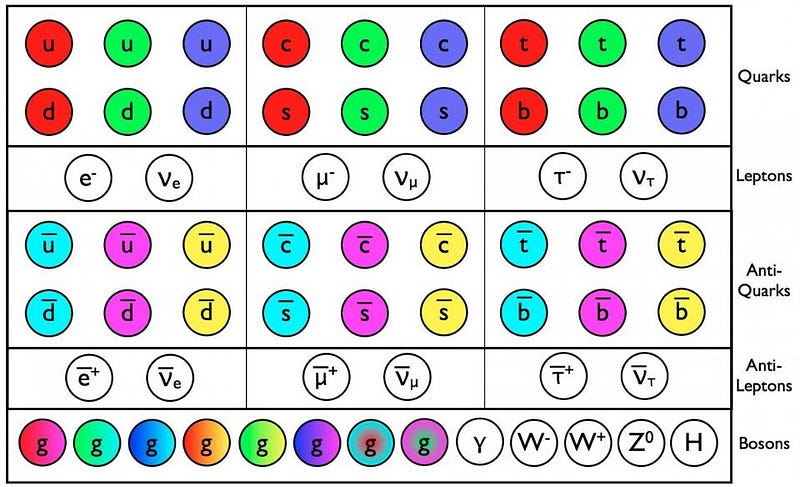

However, the strong and weak nuclear forces led to the formulation of the Standard Model in 1968, which brought the strong, weak, and electromagnetic forces under the same overarching umbrella. Particles and their interactions were all accounted for, and a slew of new predictions were made, including a big one about unification. At high energies of around 100 GeV (the energy required to accelerate a single electron to a potential of 100 billion volts), a symmetry unifying the electromagnetic and the weak forces would be restored. New, massive bosons were predicted to exist, and with the discovery of the W and Z bosons in 1983, this prediction was confirmed. The four fundamental forces were reduced down to three.

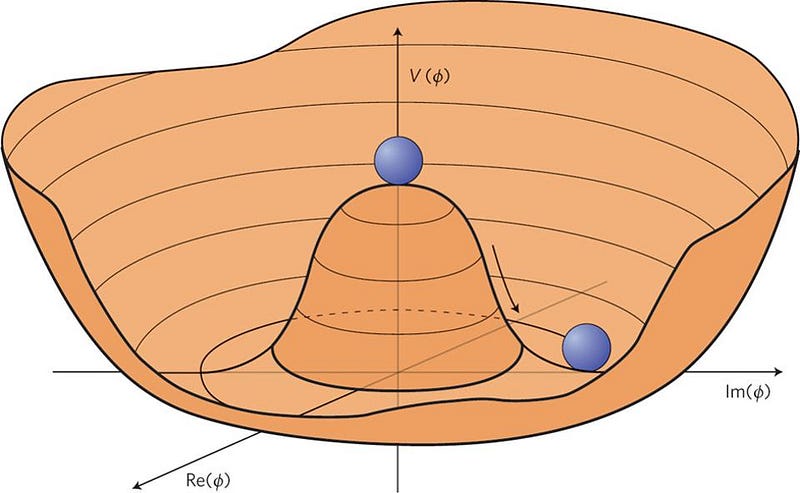

Unification was already an interesting idea, but models took off. People assumed that at higher energies still, the strong force would unify with the electroweak; that was where the idea of Grand Unification Theories (GUTs) came from. Some assumed that at even higher energies, perhaps around the Planck scale, the gravitational force would unify as well; this is one of the main motivations for string theory. What’s very interesting about these ideas, however, is that if you want to have unification, you need to restore symmetries at higher energies. And if the Universe has symmetries at high energies that are broken today, that translates into something observable: new particles and new interactions.

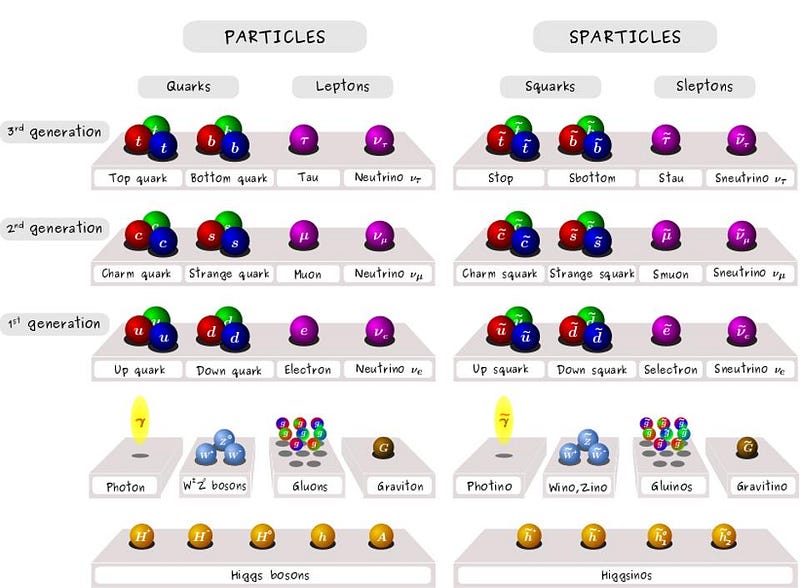

So what new particles and interactions are predicted? This depends on which variant of unification theories you go for, but include:

- Heavy, neutral, dark-matter-like particles,

- supersymmetric partner particles,

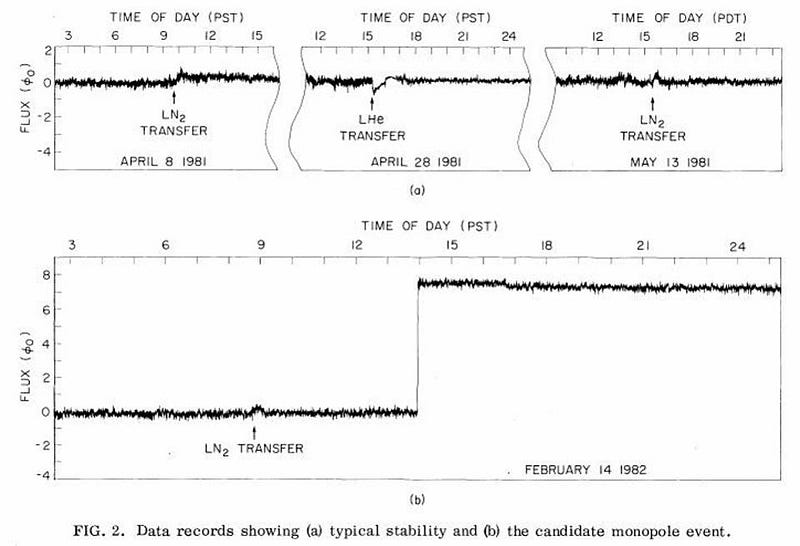

- magnetic monopoles,

- heavy, charged, scalar bosons,

- multiple Higgs-like particles,

- and particles that mediate proton decay.

Although we can be certain, from indirect observations, that there is some origin to our Universe’s dark matter, none of these particles or predicted decays have been observed to exist.

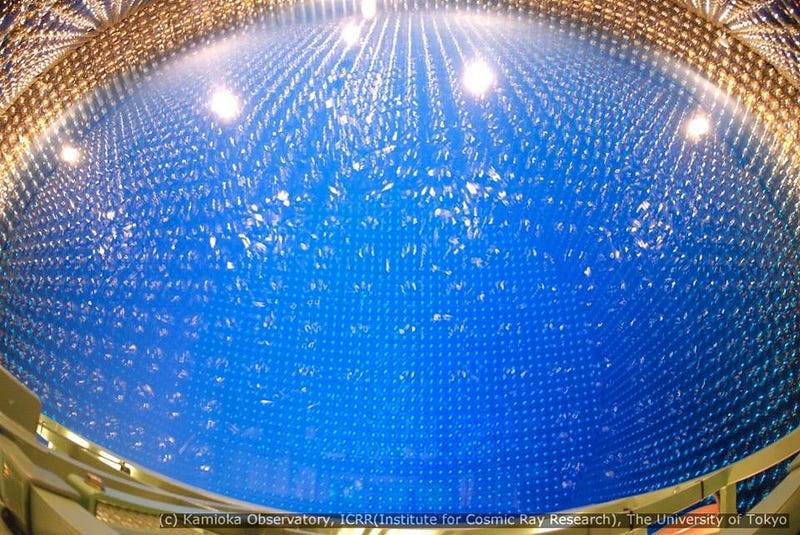

This is a pity, in many regards, because we’ve searched, and hard. In 1982, one of the experiments searching for magnetic monopoles registered a single positive result, spawning many copycats which attempted to discover large numbers of others. Unfortunately, that one positive result was anomalous, and no one has ever replicated it. Also in the 1980s, people began building giant tanks of water and other atomic nuclei, searching for evidence of proton decay. While those tanks eventually wound up being repurposed as neutrino detectors, not a single proton has ever been observed to decay. The proton lifetime is now constrained to be greater than 1035 years: some 25 orders of magnitude greater than the age of the Universe.

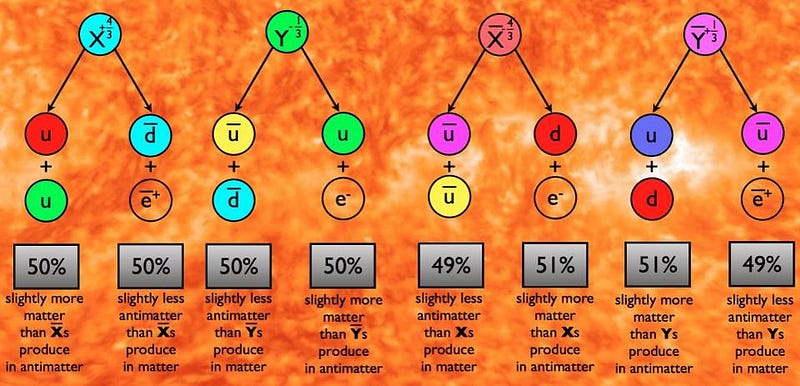

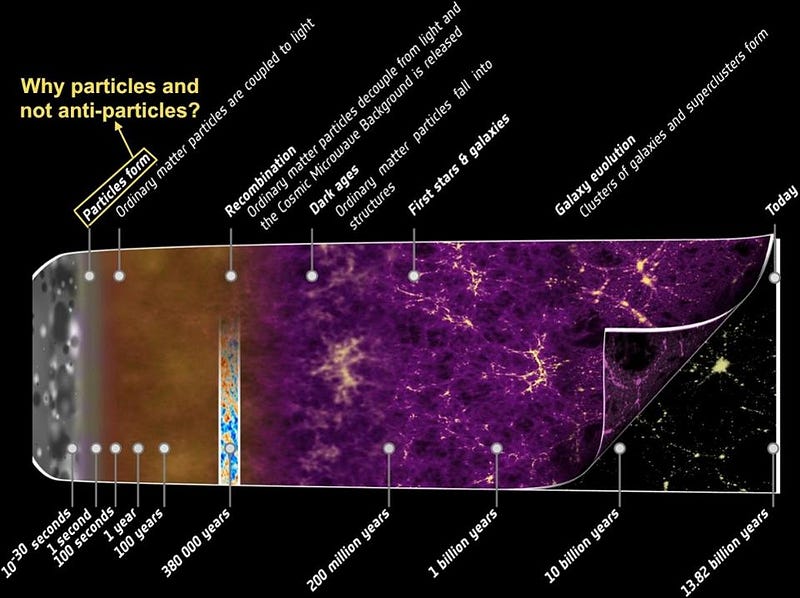

This is also too bad, because Grand Unification offers a clean and elegant path to generating the matter/antimatter asymmetry in the Universe. At very early times, the Universe is hot enough to produce matter-and-antimatter pairs of all the particles that can possibly exist. In most GUTs, two of those particles that exist are superheavy X-and-Y bosons, which are charged, and contain both quark and lepton couplings. There’s expected to be an asymmetry in the way the matter versions and the antimatter versions decay, and they can give rise to a leftover presence of matter over antimatter, even if there was none initially. Unfortunately, again, we have yet to find any positive evidence for such particles and/or interactions.

Some physicists contend that the Universe must have these symmetries, and the evidence must simply lie at energies too high for even the LHC to probe. But others are coming around to a more uncomfortable possibility: perhaps nature doesn’t unify. Perhaps there is no Grand Unified Theory that describes our physical reality; perhaps a quantum theory of gravity doesn’t unify with the other forces; perhaps the problems of baryogenesis and dark matter have other solutions that aren’t rooted in these ideas. After all, the ultimate arbiter of what the Universe is like isn’t our ideas about it, but rather the results of experiment and observations. We can only ask the Universe what it’s like; it’s up to us to listen to what it tells us and go from there.

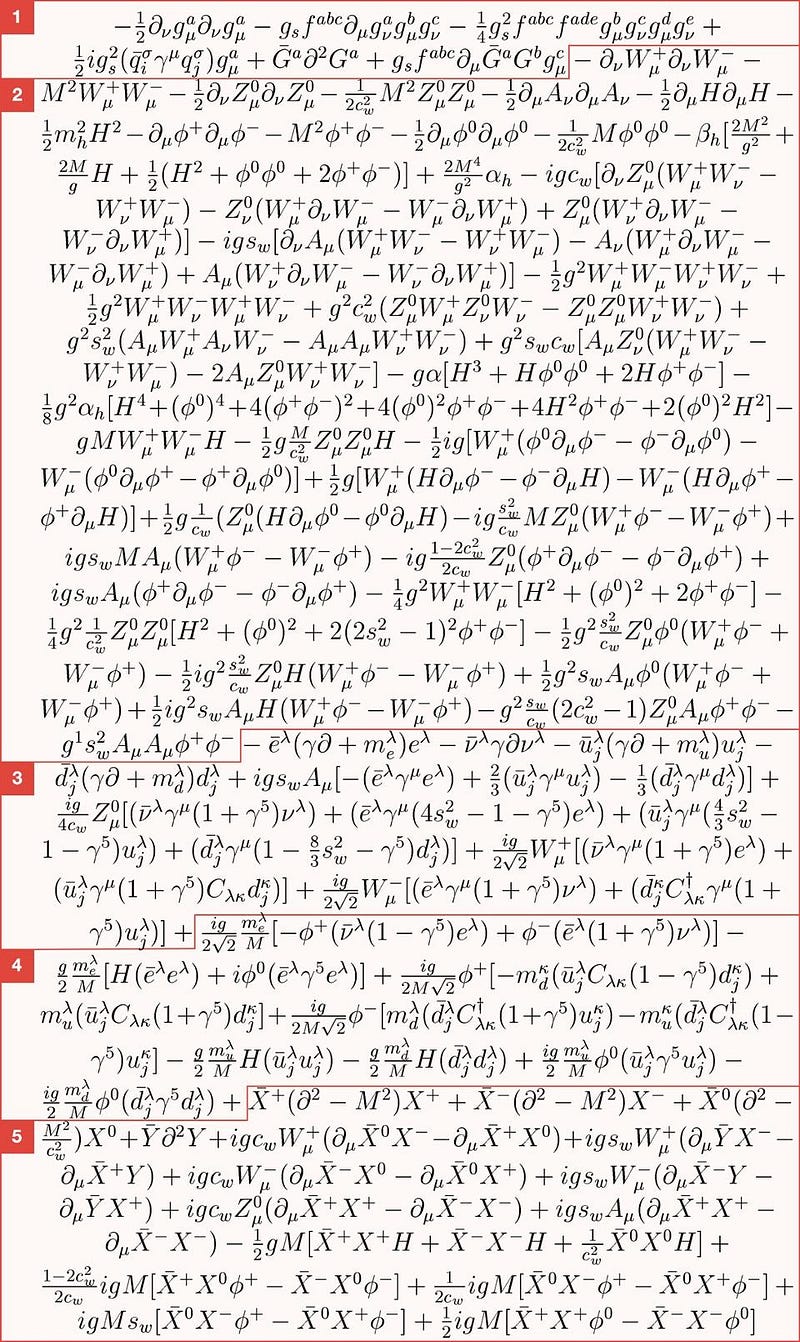

Although we can write the Standard Model as a single equation, it isn’t really a unified entity in the sense that there are multiple, separate, independent terms to govern different components of the Universe. The various parts of the Standard Model don’t interact with each other, as color charge doesn’t affect the electromagnetic or weak forces, and there are unanswered questions about why interactions that should occur, like CP-violation in the strong force, don’t.

It’s the hope of many that unification holds the answer to these questions, and will solve many of the open problems and puzzles in physics today. However, any sort of additional symmetries — symmetries which are restored at high energies but are broken today — lead to new particles, new interactions, and new physical rules that the Universe plays by. We’ve tried to reverse-engineer some predictions using what rules we’d need for things to work out, yet the particles and unifications we were hoping to find never materialized. Unification won’t help you derive emergent properties like chemistry, biology, geology, or consciousness, but will help us better understand the origin of where everything came from, and how.

Of course, there is the other possibility: that the Universe simply doesn’t unify. That the multiple different laws and rules we have are there for a reason: these symmetries that we’ve invented are simply our own mathematical inventions, and not descriptive of the physical Universe. For every elegant, beautiful, compelling physical theory that’s out there, there’s an equally elegant, beautiful, and compelling physical theory that is wrong. In these matters, as in all scientific matters, it’s up to humanity to ask the right questions. But it’s up to the Universe to tell us the answers. Whatever they are, that’s the Universe we have. It’s up to us to figure out what those answers mean.

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.