Ask Ethan: How Can LISA, Without Fixed-Length Arms, Ever Detect Gravitational Waves?

LIGO, here on Earth, has exquisitely-precise distances its lasers travel. With three spacecrafts in motion, how could LISA work?

Since it began operating in 2015, advanced LIGO has ushered in an era of a new type of astronomy: using gravitational wave signals. The way we do it, however, is through a very special technique known as laser interferometry. By splitting a laser and sending each half of the beam down a perpendicular path, reflecting them back, and recombining them, we can create an interference pattern. If the lengths of those paths change, the interference pattern changes, enabling us to detect those waves. And that leads to the best question I got about science during my recent Astrotour in Iceland, courtesy of Ben Turner, who asked:

LIGO works by having these exquisitely precise lasers, reflected down perfectly length-calibrated paths, to detect these tiny changes in distance (less than the width of a proton) induced by a passing gravitational wave. With LISA, we plan on having three independent, untethered spacecrafts freely-floating in space. They’ll be affected by all sorts of phenomena, from gravity to radiation to the solar wind. How can we possibly get a gravitational wave signal out of this?

It’s a great question, and the toughest one posed to me all year thus far. Let’s explore the answer.

Since the dawn of time, humanity has been practicing astronomy with light, which has progressed from naked-eye viewing to the use of telescopes, cameras, and wavelengths that go far beyond the limits of human vision. We’ve detected cosmic particles from space in a wide variety of flavors: electrons, protons, atomic nuclei, antimatter, and even neutrinos.

But gravitational waves are an entirely new way for humanity to view the Universe. Instead of some detectable, discrete quantum particle that interacts with another, leading to a detectable signal in some sort of electronic device, gravitational waves act as ripples in the fabric of space itself. With a certain set of properties, including:

- propagation speed,

- orientation,

- polarization,

- frequency, and

- amplitude,

they affect everything occupying the space that they pass through.

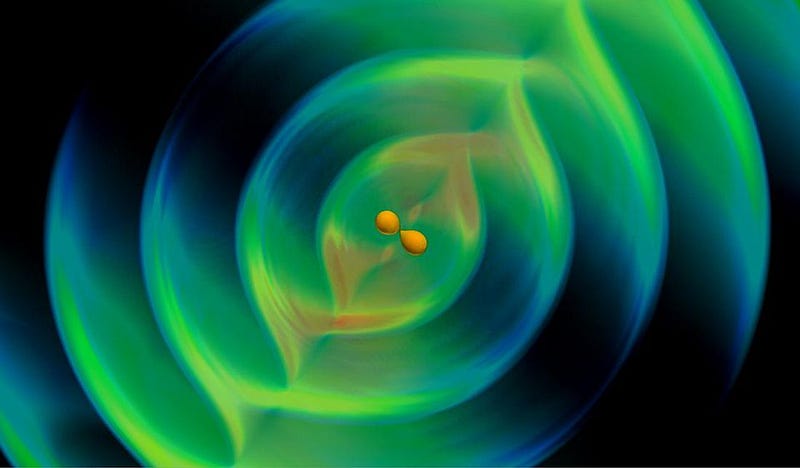

When one of these gravitational waves passes through a LIGO-like detector, it does exactly what you might suspect. The gravitational wave, along the direction it propagates at the speed of gravity (which equals the speed of light), doesn’t affect space at all. Along the plane perpendicular to its propagation, however, it alternately causes space to expand and contract in mutually perpendicular directions. There are multiple types of polarization that are possible:

- “plus” (+) polarization, where the up-down and left-right directions expand and contract,

- “cross” (×) polarization, where the left-diagonal and right-diagonal directions expand and contract,

- or “circularly” polarized waves, similar to way light can be circularly polarized; this is a different parameterization of plus and cross polarizations.

Whatever the physical case, the polarization is determined by the nature of the source.

When a wave enters a detector, any two perpendicular directions will be compelled to contract and expand, alternately and in-phase, relative to one another. The amount that they contract or expand is related to the amplitude of the wave. The period of the expansion and contraction is determined by the frequency of the wave, which a detector of a specific arm length (or effective arm length, where there are multiple reflections down the arms, as in the case of LIGO) will be sensitive to.

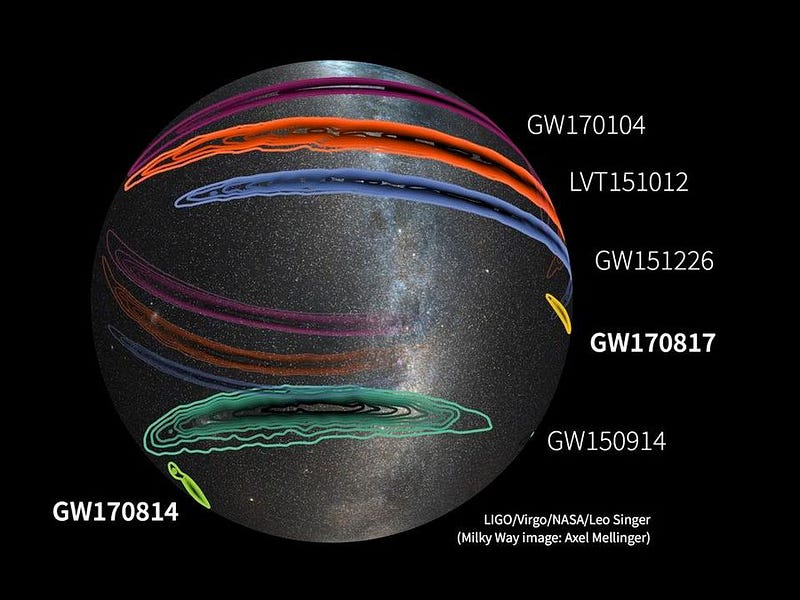

With multiple such detectors in a variety of orientations to one another in three-dimensional space, the location, orientation, and even polarization of the original source can be reconstructed. By using the predictive power of Einstein’s General Relativity and the effects of gravitational waves on the matter-and-energy occupying the space they pass through, we can learn about events happening all across the Universe.

But it’s only due to the extraordinary technical achievement of these interferometers that we can actually make these measurements. In a terrestrial, LIGO-like detector, the distances of the two perpendicular arms are fixed. Laser light, even if reflected back-and-forth along the arms thousands of times, will eventually see the two beams come back together and construct a very specific interference pattern.

If the noise can be minimized below a certain level, the pattern will hold absolutely steady, so long as no gravitational waves are present.

If, then, a gravitational wave passes through, and one arm contracts while the other expands, the pattern will shift.

By measuring the amplitude and frequency at which the pattern shifts, the properties of a gravitational wave can be reconstructed. By measuring a coincident signal in multiple such gravitational wave detectors, the source properties and location can be reconstructed as well. The more detectors with differing orientations and locations are present, the better-constrained the properties of the gravitational wave source will be.

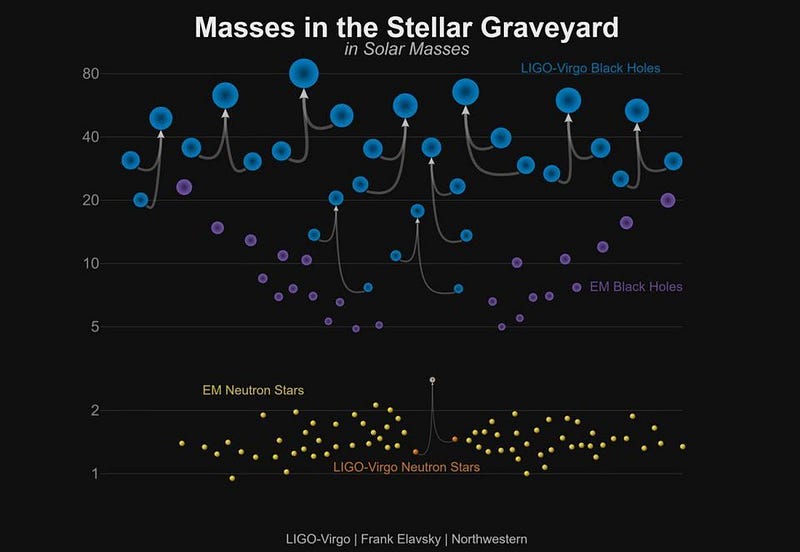

This is why adding the Virgo detector to the twin LIGO detectors in Livingston and Hanford enabled a far superior reconstruction of the location of gravitational wave sources. In the future, additional LIGO-like detectors in Japan and India will allow scientists to pinpoint gravitational waves in an even superior fashion.

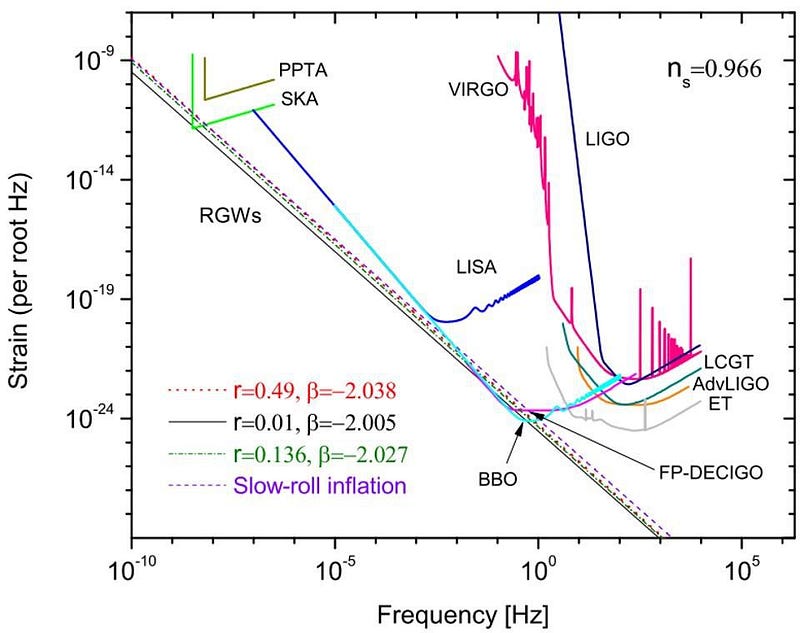

But there’s a limit to what we can do with detectors like this. Seismic noise from being located on the Earth itself limits how sensitive a ground-based detector can be. Signals below a certain amplitude can never be detected. Additionally, when light signals are reflected between mirrors, the noise generated by the Earth accumulates cumulatively.

The fact that the Earth itself exists in the Solar System, even if there were no plate tectonics, ensures that the most common type of gravitational wave events — binary stars, supermassive black holes, and other low-frequency sources (taking 100 seconds or more to oscillate) — cannot be seen from the ground. Earth’s gravitational field, human activity, and natural geological processes means that these low-frequency signals cannot be practically seen from Earth. For that, we need to go to space.

And that’s where LISA comes in.

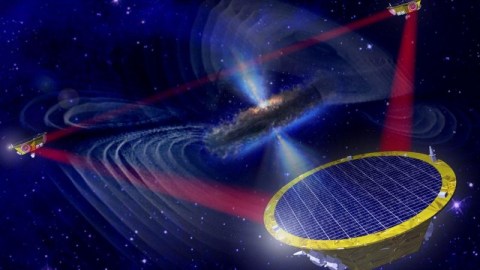

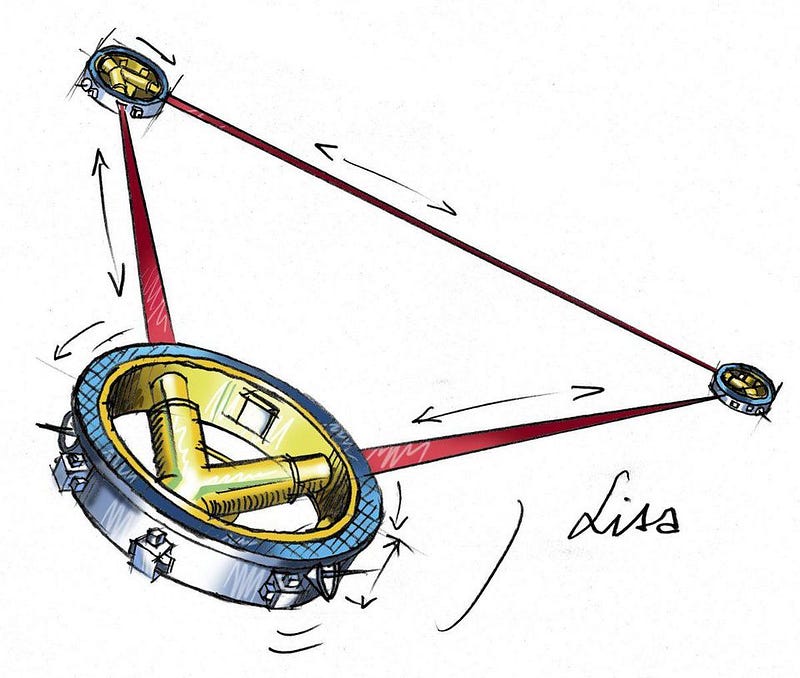

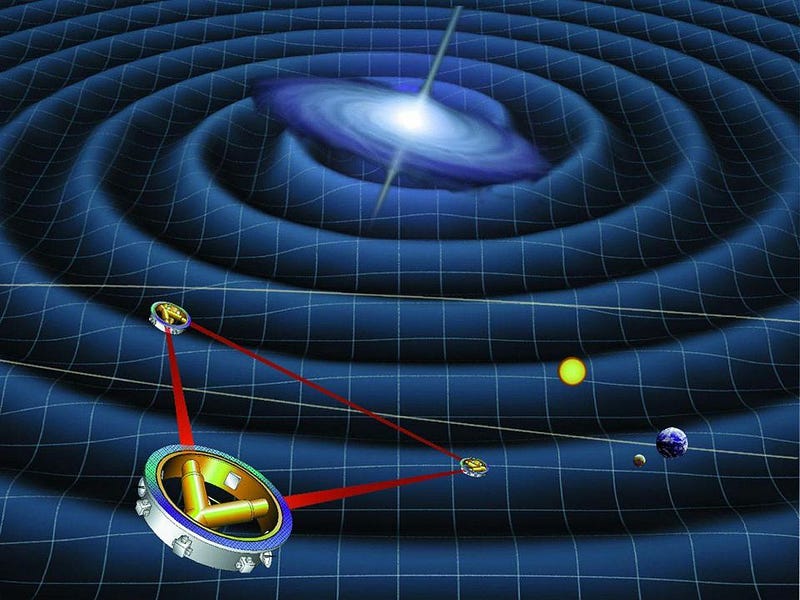

LISA is the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna. In its current design, it consists of three dual-purpose spacecrafts, separated in an equilateral triangle configuration by roughly 5,000,000 kilometers along each laser arm.

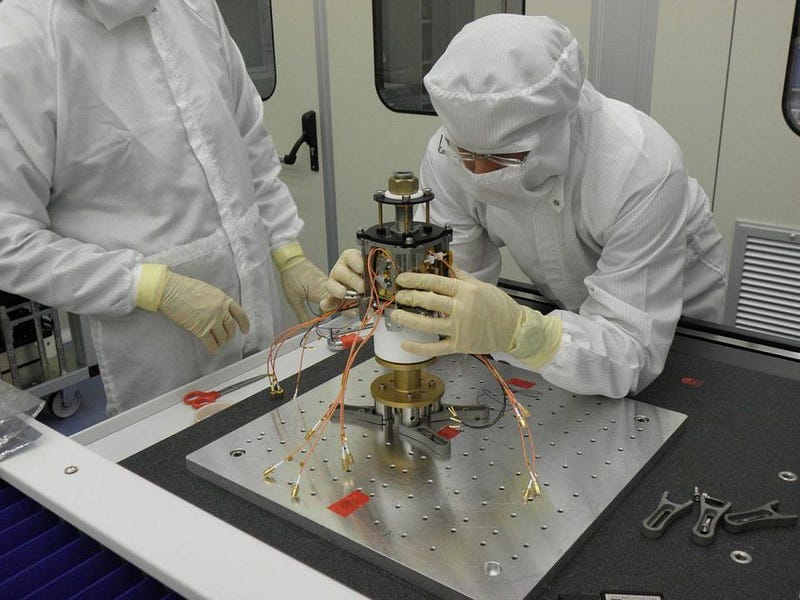

Inside each spacecraft, there are two free-floating cubes that are shielded by the spacecraft itself from the effects of interplanetary space. They will remain at a constant temperature, pressure, and will be unaffected by the solar wind, radiation pressure, or the bombardment of micrometeorites.

By carefully measuring the distances between pairs of cubes on different spacecrafts, using the same laser interferometry technique, scientists can do everything that multiple LIGO detectors do, except for these long-period gravitational waves that only LISA is sensitive to. Without the Earth to create noise, it seems like an ideal setup.

But even without the terrestrial effects of human activity, seismic noise, and being deep within Earth’s gravitational field, there are still sources of noise that LISA must contend with. The solar wind will strike the detectors, and the LISA spacecrafts must be able to compensate for that. The gravitational influence of other planets and solar radiation pressure will induce tiny orbital changes relative to one another. Quite simply, there is no way to hold the spacecract at a fixed, constant distance of exactly 5 million km, relative to one another, in space. No amount of rocket fuel or electric thrusters will be able to maintain that exactly.

Remember: the goal is to detect gravitational waves — themselves a tiny, minuscule signal — over and above the background of all this noise.

So how does LISA plan to do it?

The secret is in these gold-platinum alloy cubes. In the center of each optical system, a solid cube that’s 4 centimeters (about 1.6″) on each side floats freely in the weightless conditions of space. While external sensors monitor the solar wind and solar radiation pressure, with electronic sensors compensating for those extraneous forces, the gravitational forces from all the known bodies in the Solar System can be calculated and anticipated.

As the spacecrafts, and the cubes, move relative to one another, the lasers adjust in a predictable, well-known fashion. So long as they continue to reflect off of the cubes, the distances between them can be measured.

It’s not a matter of keeping the distances fixed and measuring a tiny change due to a passing wave; it’s a matter of understanding exactly how the distances will behave over time, accounting for them, and then looking for the periodic departures from those measurements to a high-enough precision. LISA won’t hold the three spacecrafts in a fixed position, but will allow them to adjust freely as Einstein’s laws dictate. It’s only because gravity is so well-understood that the additional signal of the gravitational waves, assuming the wind and radiation from the Sun is sufficiently compensated for, can be teased out.

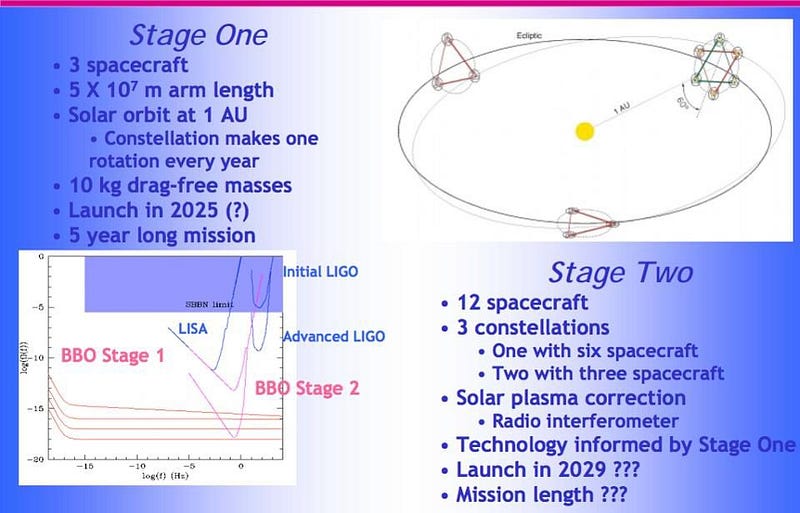

If we want to go even farther, we have dreams of putting three LISA-like detectors in an equilateral triangle around different points in Earth’s orbit: a proposed mission called Big Bang Observer (BBO). While LISA can detect binary systems with periods ranging from minutes to hours, BBO will be able to detect the grandest behemonths of all: supermassive binary black holes anywhere in the Universe, with periods of years.

If we’re willing to invest in it, space-based gravitational wave observatories could allow us to map out all of the most massive, densest objects located throughout the entire Universe. The key isn’t holding your laser arms fixed, but simply in knowing exactly how, in the absence of gravitational waves, they’d move relative to one another. The rest is simply a matter of extracting the signal of each gravitational wave out. Without the Earth’s noise to slow us down, the entire cosmos is within our reach.

Ethan’s next Astrotour will be to Chile in November; bookings are available now. In the meantime, you can submit your Ask Ethan questions by emailing startswithabang at gmail dot com!

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.