Ask Ethan: Did We Just Find The Universe’s Missing Black Holes?

A longstanding astronomical gap between neutron stars and black holes is finally coming to a close.

Astronomy has taken us so far into the Universe, from beyond Earth to the planets, stars, and even the galaxies far beyond our Milky Way. We’ve discovered exotic objects along the way, from interstellar visitors to rogue planets to white dwarfs, neutron stars and black holes.

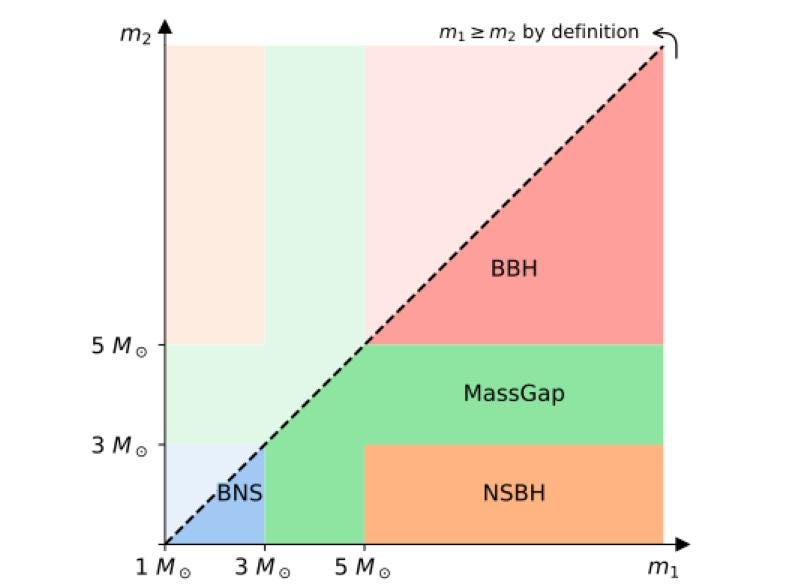

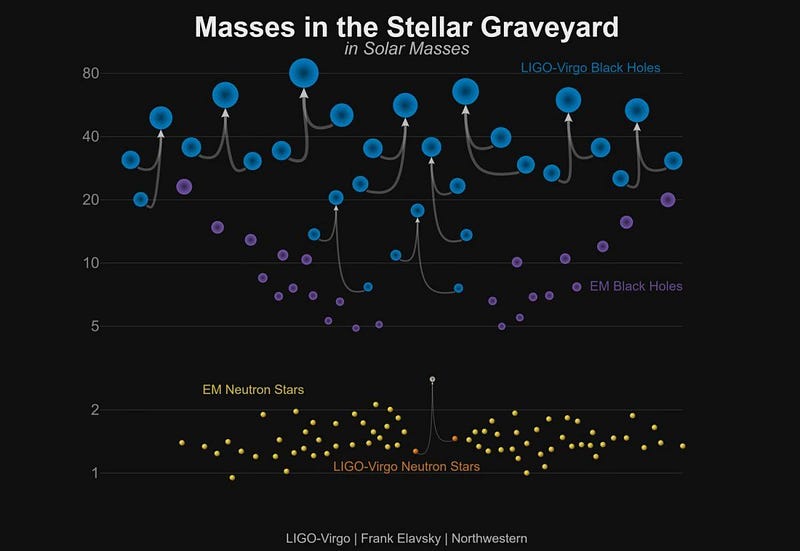

But those last two are kind of funny. They both typically form from the same mechanism: the collapse of a very massive star that results in a supernova explosion. Even though stars come in all different masses, the most massive neutron star was only about 2 solar masses while the least massive black hole was already 5 solar masses, as of 2017. What’s with the gap, and are there any black holes or neutron stars in between? Patreon supporter Richard Jowsey points to a new study and asks:

This low-mass collapsar is smack-dab on the “mind the gap” borderline. How can we tell whether it’s a neutron star or a black hole?

Let’s dive into what astronomers call the mass gap and find out.

Before gravitational waves came along, there were only two ways we knew of to detect black holes.

- You could find a light-emitting object, like a star, that was orbiting a large mass that emitted no light of any type. Based on the luminous object’s light curve and how it changed over time, you could gravitationally infer the presence of a black hole.

- You could find a black hole that’s gathering matter from either a companion star, an infalling mass, or a cloud of gas that flows inward. As the material approaches the black hole’s event horizon, it will heat up, accelerate, and emit what we detect as X-ray radiation.

The first black hole ever discovered was found by this latter method: Cygnus X-1.

Since that first discovery 55 years ago, the known population of black holes has exploded. We now know that supermassive black holes lie at the centers of most galaxies, and feed on and devour gas regularly. We know that there are black holes that likely originated from supernova explosions, as the number of black holes in X-ray emitting, binary systems is now quite large.

We also know that only a fraction of the black holes out there are active at any given time; most of them are probably quiet. Even after LIGO turned on, revealing black holes merging with other black holes, one puzzling fact remained: the lowest-mass black hole we had ever discovered have all had masses that were at least five times the mass of our Sun. There were no black holes with three or four solar masses worth of material. For some reason, all the known black holes were above some arbitrary mass threshold.

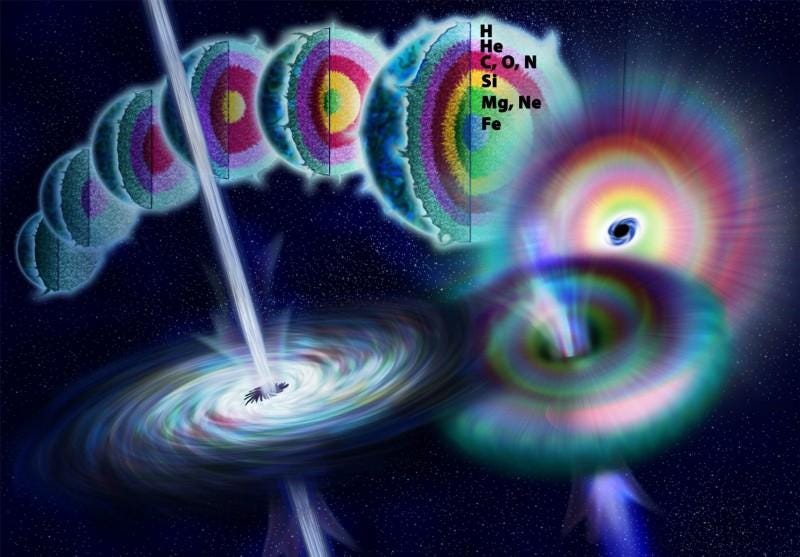

Theoretically, there is disagreement about what ought to be out there as far as black hole masses go. According to some theoretical models, there is a fundamental difference between the supernova processes that wind up producing black holes and the ones that wind up producing neutron stars. Although both arise from Type II supernovae, when the cores of the progenitor stars implode, whether you cross a critical threshold (or not) could make all the difference.

If correct, then crossing that threshold and forming an event horizon could compel significantly more matter to wind up in the collapsing core, contributing to the eventual black hole. The minimum mass of the final-state black hole could be many solar masses above the mass of the heaviest neutron star, which never forms an event horizon or crosses that critical threshold.

On the other hand, other theoretical models don’t predict a fundamental difference between the supernova processes that do or don’t create an event horizon. It’s entirely possible, and a significant number of theorists come to this conclusion instead, that supernovae wind up producing a continuous distribution of masses, and that neutron stars will be found all the way up to a certain limit, followed immediately by black holes that leave no mass gap.

Up until 2017, observations seemed to favor a mass gap. The most massive known neutron star was right around 2 solar masses, while the least massive black hole ever seen (through X-ray emissions from a binary system) was right around 5 solar masses. But in August of 2017, an event happened that kicked off a tremendous change in how we think about this elusive mass range.

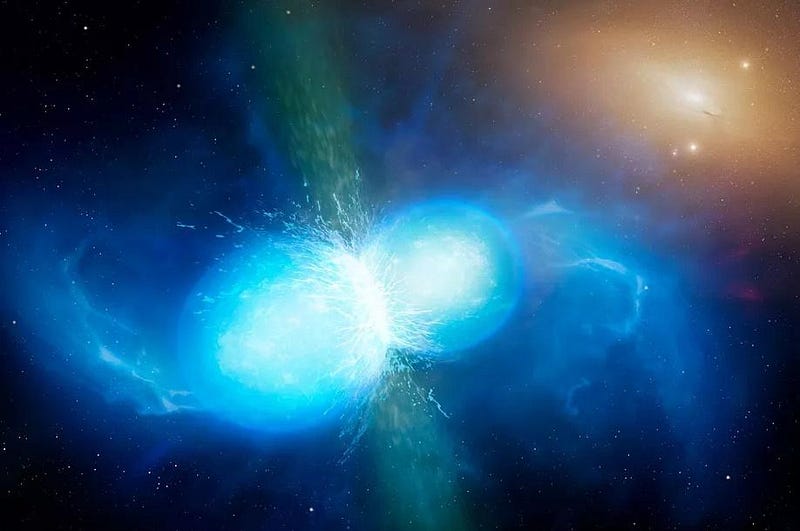

For the very first time, an event occurred where not only gravitational waves were detected, but also emitted light. From over 100 million light-years away, scientists observed signals from all across the spectrum: gamma rays to visible signals all the way down to radio waves. They indicated something we had never seen before: two neutron stars merged together, creating an event called a kilonova. These kilonovae, we now believe, are responsible for the majority of the heaviest elements found throughout the Universe.

But perhaps most remarkably, from the gravitational waves that arrived, we were able to extract an enormous amount of information about the merger process. Two neutron stars merged to form an object that, it appears, initially formed as a neutron star before, fractions of a second later, collapsing to form a black hole. For the first time, we’d found an object in the mass gap range, and it was, indeed, a black hole.

However, that absolutely does not mean that there’s no mass gap. It’s eminently possible that neutron star-neutron star mergers will often form black holes if their combined mass is over a certain threshold: between 2.5 and 2.75 solar masses, dependent on how fast it’s spinning.

But even if that’s true, it’s still possible that the neutron stars produced by supernovae will top out at a certain threshold, and that the black holes produced by supernovae won’t appear until a significantly higher threshold. The only ways to determine if that type of mass gap is real would be to either:

- take a large census of supernovae and supernova remnants and measure the mass distribution of the central neutron stars/black holes produced,

- or to collect superior data that actually measured the distribution of object in that so-called mass gap range, and determine whether there’s a gap, a dip, or a continuous distribution.

In a study just released two months ago, the gap closed a little bit more.

By finding a neutron star that ate into the mass gap range a little bit, using a technique involving pulsar timing and gravitational physics, we were able to confirm that we still get neutron stars below the anticipated 2.5 solar mass threshold. The orbital technique that works for black holes also works for neutron stars and any massive object. So long as there’s some form of a light or gravitational wave signal you can measure, the gravitational effects of mass can be inferred.

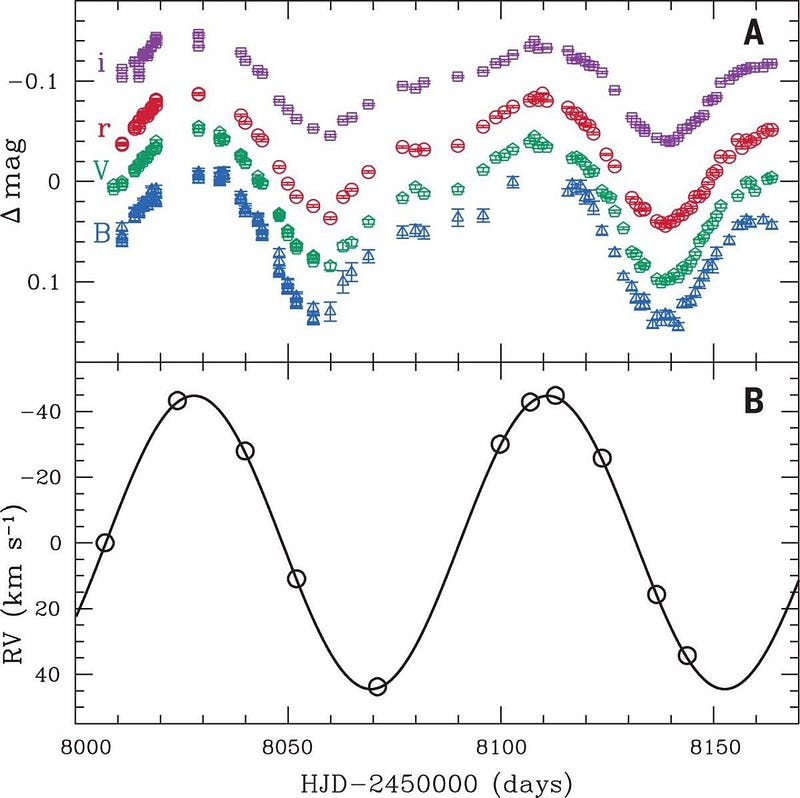

But just about six weeks after this neutron star story came out, another even more exciting story hit the news. About 10,000 light-years away, right in our own galaxy, scientists took precision observations of a giant star, thought to be a few times the mass of our Sun. Its orbit, fascinatingly, showed that it was orbiting an object that emitted no radiation at all of any type. From its gravity, that object is right around 3.3 solar masses: solidly in the mass gap range.

We can’t be absolutely certain this object isn’t a neutron star, but the super strong magnetic fields of even quiet neutron stars should lead to X-ray emissions that fall well below the observed thresholds. Even given the uncertainties, which could admit a mass as low as about 2.6 solar masses (or as high as around almost 5 solar masses), this object is strongly indicated to be a black hole.

This supports the idea that above 2.75 solar masses, there are no more neutron stars: the objects are all black holes. It shows that we have the capability of finding black holes that are smaller in mass simply by its gravitational effects on any orbiting companions.

We’re pretty confident that this stellar remnant is a black hole and not a neutron star. But what about the big question? What about the mass gap?

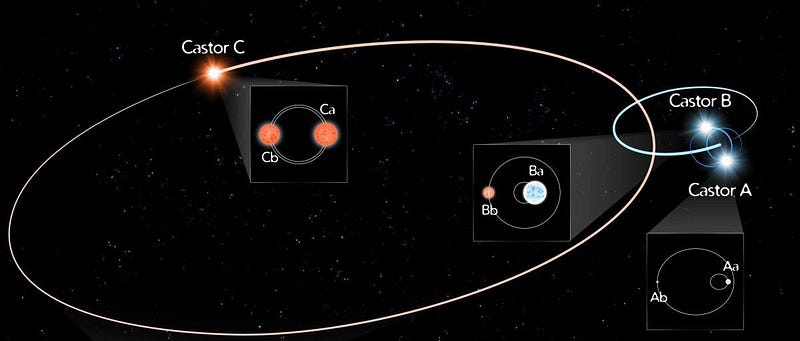

As interesting as this new black hole is, and it really is most likely a black hole, it cannot tell us whether there’s a mass gap, a mass dip, or a straightforward distribution of masses arising from supernova events. About 50% of all the stars ever discovered exist as part of a multi-star system, with approximately 15% in bound systems containing 3-to-6 stars. Since the multi-star systems we see often have stellar masses similar to one another, there’s nothing ruling out that this newfound black hole didn’t have its origin from a long-ago kilonova event of its own.

So the object itself? It’s almost certainly a black hole, and it very likely has a mass that puts it squarely in a range where at most one other black hole is known to exist. But is the mass gap a real gap, or just a range where our data is deficient? That will take more data, more systems, and more black holes (and neutron stars) of all masses before we can give a meaningful answer.

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.