Four billion years ago, the Universe was a different place. What would we have seen?

“In such moments, offering up his heart at the hour when the flowers of night inhale their perfume, lighted like a lamp in the center of the starry night, expanding his soul in ecstasy in the midst of the universal radiance of creation, he could not himself perhaps have told what was passing in his own mind; he felt something depart from him, and something descend upon him, mysterious interchanges of the depths of the soul with the depths of the universe.” –Victor Hugo

While the stars in the night sky seem to be virtually static and unchanging over the span of a human lifetime, our world has been around for billions of years. That’s plenty of time for all sorts of things to happen: for stars to be born, burn through their fuel and die, for galaxies to merge, for the Universe to expand, etc. It’s enough to make you wonder how different those long-ago-skies would’ve been! At least, that’s what it made Scott Elrick wonder, when he submitted this question for Ask Ethan:

In general, what would the night time skies have looked like to an observer on a newly cooling Earth 4 billion years ago? Would the night sky be the same? Brighter?

In order to understand what the skies would’ve looked like so long ago, we first need to come to terms with what we’re looking at today.

As much as it might feel like we’re looking out into the depths of infinity when we gaze into the distant Universe, the reality is that we’re seeing a combination of two things in general: the stars that are both closest to us and intrinsically brightest in their nature. The brightest ten stars in the night sky include some of the closest, like Sirius and Alpha Centauri, each less than 10 light years away, but also some of the most luminous, like Rigel and Betelgeuse, which are hundreds of light years distant but shine over 100,000 times as brightly as our Sun.

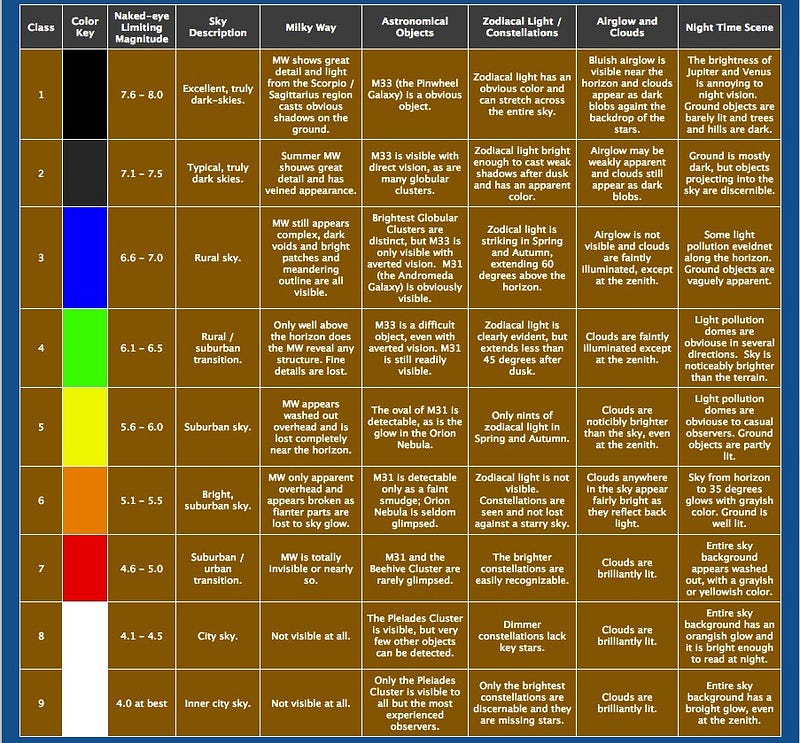

In order for someone with our vision capabilities — with human eyes — to see a star, it needs to be of apparent magnitude +6 or brighter, roughly, or it will be beyond the limit of human vision. This requires a combination of closeness and brightness for stars that the vast majority of stars in the Milky Way can’t reach. From our vantage point on Earth, we have only about 6,000 stars visible over the entire celestial sphere that are visible by unaided human vision.

That also assumes, mind you, that you’re not living in a light-polluted area, or that the brightness of sources from both the sky and the ground aren’t illuminating the Earth’s atmosphere to such a degree that the stars become invisible against the lighted backdrop.

There are very few things that can compete with these limits of human vision, but the Universe gives us some wondrous attempts. In particular, individual stars might have these limits on them from the brightness/distance relationship, but diffuse, extended objects can appear much brighter. Certain star clusters, globular clusters, and even entire galaxies will appear visible from the Earth’s night sky when the light pollution is low, but these classes of objects — where the light is spread out over a larger surface area — will be the first to go when the light pollution is significant.

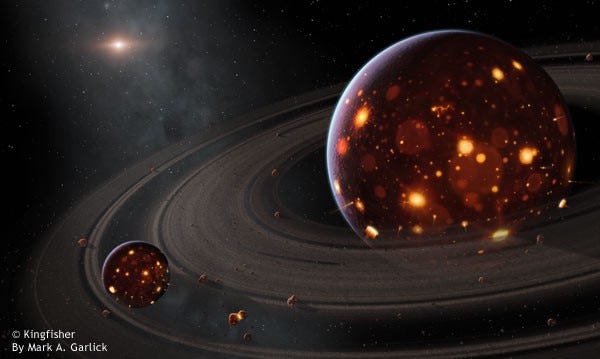

That said, the Earth, the Solar System, the galaxy and the Universe were very different in the Universe’s distant past, and there are a number of ways this would have contributed to the night sky being very, very different a long time ago. Assuming you had the same, human eyes, what would we have seen between 4-and-4.5 billion years ago, when the Solar System was first forming and undergoing its initial stages of evolution?

More and brighter planets in our skies. If you’ve been checking out the eastern skies just before dawn, you’ve probably noticed a series of bright lights there. In addition to the bright blue star, Regulus, the planets Venus, Mars, Jupiter and even Mercury are clustered there right now, with Venus outshining them all.

But not only were there possibly even more planets in our Solar System early in its history, as simulations tend to indicate, but Jupiter, Saturn, and even Uranus and Neptune may have been much closer in towards the Sun billions of years ago, as the Nice model indicates.

While Uranus today is at the limit of unaided vision, Jupiter and Saturn would have both been brilliant, and Uranus and Neptune — and potentially even another planet that’s since been ejected — would have been visible to the naked eye. Remember, in our Solar System, we see only the survivors when we look today!

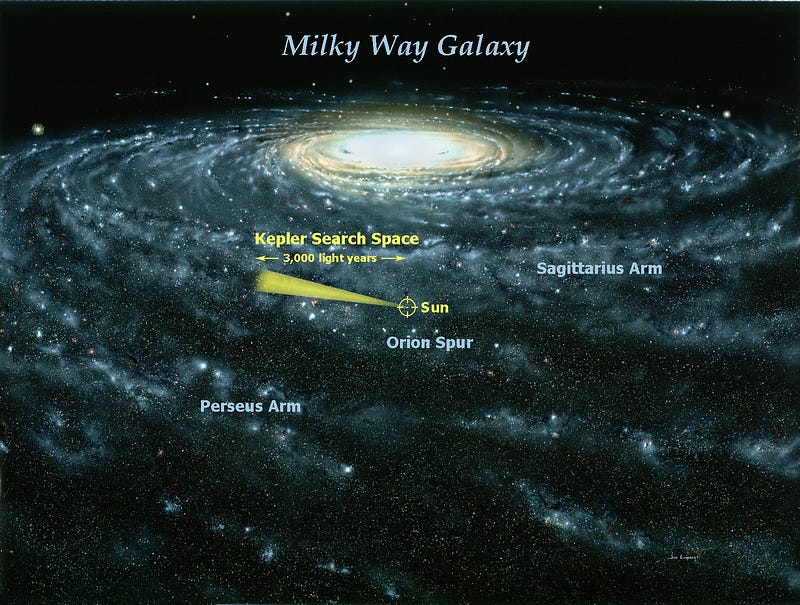

Thousands of additional bright, brilliant stars. When we look out at the nearest star today, it’s more than four light years distant from us. In fact, if we were to survey all the stars within some 30 light years of us in any direction, there are about 300 of them: with very few others likely to be present.

But our Sun, like all stars, didn’t form in isolation. Rather, some 4.5 billion years ago, our Sun was part of a giant star-forming region that most likely gave rise to thousands of stars, many of which are dimmer than our own, but some of which were far, far brighter.

From within one of these clusters, it would have originally appeared very dusty, as our Solar System needed to shake out from this proto-planetesimal-filled debris. But as the dust settled and was blown off, we would have found our sky filled with thousands upon thousands of stars, closer and more brilliant than even the brightest star in our skies today.

For a time of tens of millions of years or more, the skies would have been absolutely glittering at night.

The formation of the Moon would have made things a mess! Around 50-to-100 million years after the Earth formed, a proto-planet named Theia collided with Earth, kicking up debris which coalesced in relatively short order into the Moon.

However! Both the Moon and the surface of the Earth were very hot for a long time — likely millions of years — after that, meaning that they would have emitted so much visible light that the night sky would have been brightened from Earth significantly. Imagine that: our planet was so hot that we made our own light pollution just by radiating heat!

After a few hundred million years, the star cluster that formed us began to dissociate. Open star clusters, like the one that gave rise to our Sun and Solar System, rarely last more than half a billion years before gravitational interactions drive them apart and eject the vast majority of their stars. Once we got kicked out, the night sky we saw shortly after differed only in individual details from the skies we see today.

As we orbit through the galaxy — as stars become relatively nearer to or farther from us — and as the O-and-B stars die and are born in new clusters, the individual stars that we see at any given time may change, but the number and brightness of stars remains roughly the same. Sure, we may find ourselves nearer or farther from star clusters (like the Hyades or Pleiades), star-forming regions like the Orion Nebula, or on the other side of our galaxy, which may make extra-galactic objects like Maffei 1 and Maffei 2 occasionally visible.

But the distant, diffuse objects, including other galaxies, are not likely to have been much different even four billion years ago, as the expansion of the Universe (which only affects super-galactic scales) would only have made maybe two or three additional galaxies invisible to the naked eye over that time. On the contrary, it’s far more likely that smaller galaxies that have since been cannibalized by our Milky Way would have been visible, while the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds might have been too distant to see back then!

So to answer your question, Scott, the night sky has changed tremendously in detail, but most of the changes have come from what environment our Sun finds itself in at any given point in time. The skies we see these days might seem unchanging to us on our short timescales, but to an observer four billion years ago, everything we see today — with the possible exception of Andromeda — would appear completely foreign.

Have a question or suggestion for Ask Ethan? Submit it for our consideration.

Leave your comments at our forum, and if you really loved this post and want to see more, support Starts With A Bang and get some rewards on our Patreon!