A ‘Habitable’ World Around Proxima Centauri May Not Be Very Earth-Like

Now that we know the closest star has a potentially habitable planet, it’s time to ask if it’s really like ours.

“To consider the Earth as the only populated world in infinite space is as absurd as to assert that in an entire field sown with millet, only one grain will grow.” –Metrodorus of Chios

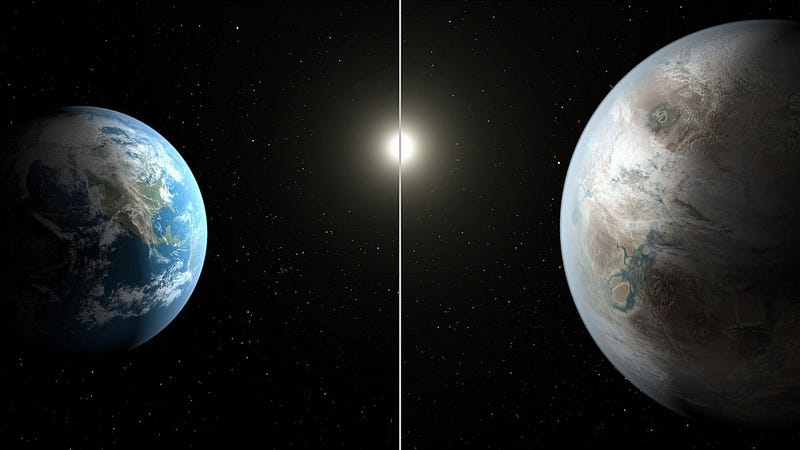

One of the ultimate goals of humanity, when looking out at the Universe, it to discover another planet capable of supporting human life, or perhaps even containing other intelligent, living beings. Beyond our Solar System, the nearest stars are the trinary system Alpha Centauri, consisting of Alpha Centauri A, a sun-like star, Alpha Centauri B, a star slightly smaller and cooler than our Sun, and Proxima Centauri, a low-mass red dwarf that’s the closest one of all. Last week, the European Southern Observatory made an announcement, stating that there’s an Earth-like planet around Proxima Centauri, just 4.24 light years away. With an estimated mass of 1.3 times Earth and receiving 70% of the incident sunlight, the world makes a complete revolution around its star in just 11 days. If verified, this would be the closest planet outside of our Solar System ever discovered.

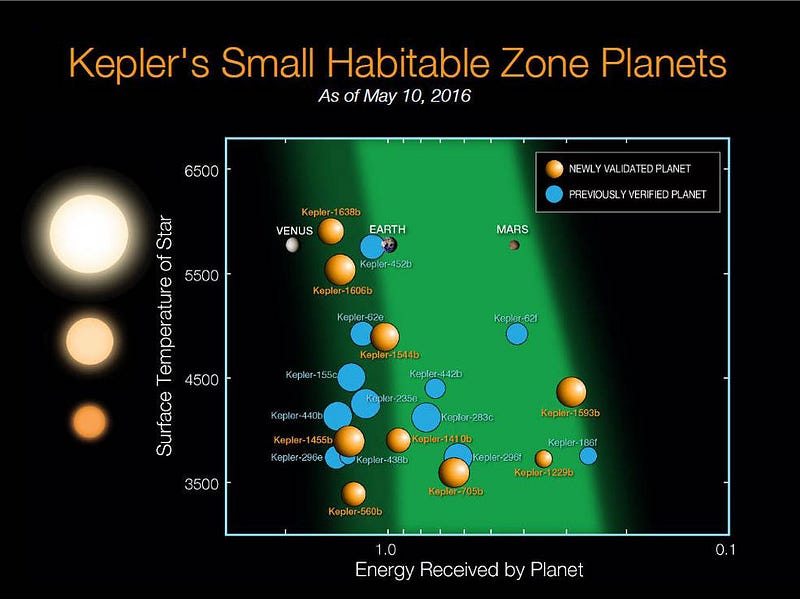

If you had come to the world’s leading scientists a mere 25 years ago and asked how many planets there were around stars other than our own, all you would have gotten were guesses. None had ever been discovered and confirmed, and the few “claimed detections” that had existed were all overturned. Fast-forward to the present day, and we have thousands of confirmed planets with thousands more as “candidates” waiting in the wings. Most of these were uncovered by NASA’s Kepler mission, which viewed a portion of a nearby spiral arm, looking at 150,000 stars hundreds to thousands of light years away. Although that information was enough to tell us that most stars have planets and that a significant percentage have rocky worlds in the potentially habitable zones of their star systems, it doesn’t hold the same allure that the nearest stars do.

Most of us hear “Earth-like” and immediately think of a world with continents and oceans, teeming with life, and possibly with intelligent beings on its surface. But that’s not what “Earth-like” means to an astronomer, at least, not yet. There’s very little we’re capable of measuring at this point in time about a distant planet, particularly from a small planet, as the light from its parent star absolutely swamps every other signal. All we can definitively measure is a planet’s physical mass, radius and orbit. If we get lucky, we can measure whether the planet has an atmosphere or not, but that information is typically only available for gas giant worlds, not for rocky planets.

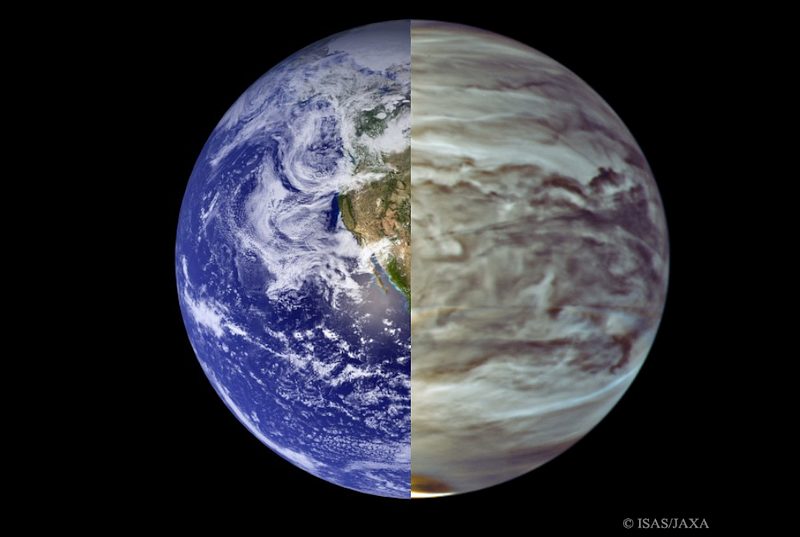

If we did indeed find an Earth-mass, Earth-sized planet orbiting around Proxima Centauri at the right distance for liquid water on its surface, it gives us tremendous hope that Earth-like worlds are present around perhaps even most of the stars in the Universe. After all, only 5% of all stars are as massive as our own Sun, while 75% of stars are red dwarfs like Proxima Centauri. Based on mass and size measurements, we could confirm that the planet is rocky, rather than gas-like or with a hydrogen/helium envelope. And if we could measure the light from the planet directly, using a variety of astronomical techniques to subtract the light from the parent star, we might even be able to tell whether the planet appears uniform over time (like a fully-clouded world like Venus does) or whether it has brightness features that change over time (like a partially clouded world like Earth does).

There are other things we’d know as well about how this world is different from our own. Based on the planet’s mass, size and distance to its star, we’d know that it was tidally locked, meaning that the same hemisphere always faces the star, similar to how the Moon is locked to Earth. We’d know that its years are much shorter, and that its seasons would be determined by its orbit’s ellipticity, not by axial tilt.

But most striking are the things we wouldn’t yet know, which include:

- Whether this world has a surface temperature like Venus, like Earth or like Mars , which depend very strongly on properties we can’t measure like the atmosphere’s composition.

- Whether there’s the potential for liquid water on its surface, which requires the knowledge of atmospheric pressure.

- Whether there’s a magnetic field shielding the planet from solar radiation, or whether that’s necessary to protect any life that arose on the world.

- Whether solar activity has fried any life that could have existed in the early stages.

- Or whether the atmosphere has any biosignatures or not.

Whether this planet exists or not — and it’s important to be skeptical, as there was a planet reported around Alpha Centauri B a few years ago that went away with more data — it’s important to remember that “Earth-like” is a far cry from being anything at all like the actual Earth. By these criteria, Venus or Mars would be “Earth-like” too, but you wouldn’t stake your hopes of becoming an interstellar species on either of those. As great as finding a new, rocky world in the potentially habitable zone around the nearest star to the Sun would be, it’s a long way from our ultimate dream of an Earth 2.0.

This post first appeared at Forbes, and is brought to you ad-free by our Patreon supporters. Comment on our forum, & buy our first book: Beyond The Galaxy!