Three habits to master long-term thinking

- Independence, curiosity, and resilience are key to long-term thinking.

- We have to be willing to do hard, laborious, ungratifying things today — the kind of things that make little sense in the short term — so we can enjoy exponential results in the future.

- Big goals often are impossible in the short term. But with small, methodical steps, almost anything is attainable.

The following is adapted from Dorie Clark’s The Long Game: How to Be a Long-Term Thinker in a Short-Term World (Harvard Business Review Press, September 2021) and is reprinted with permission of the author.

Almost everyone agrees that strategic thinking is important: a full 97% of senior executives in a 10,000-person study said that being strategic was critical to their organization’s future success.

But in practice, actually doing it — carving out time for long-term thinking amidst the urgent, and dealing with blowback from stakeholders that want faster, short-term results — is profoundly difficult.

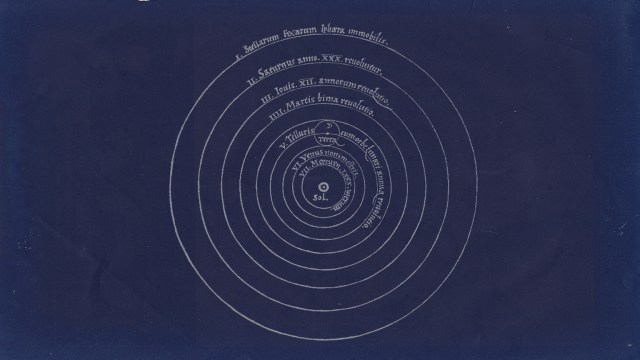

In fact, Jeff Bezos — architect of such massively profitable long-term innovations such as Amazon Web Services and Amazon Prime — noted that much of Amazon’s success comes from the fact that its competitors operate on a much shorter timeframe than they do. “If everything you do needs to work on a three-year time horizon,” he told Wired magazine in 2011, “then you’re competing against a lot of people. But if you’re willing to invest on a seven-year time horizon, you’re now competing against a fraction of those people, because very few companies are willing to do that. Just by lengthening the time horizon, you can engage in endeavors that you could never otherwise pursue.”

As it happens, the same principle that holds true in business applies to our own lives and careers — a prospect I examined in my new book The Long Game: How to Be a Long-Term Thinker in a Short-Term World.

Most of us, truth be told, aren’t ambitious enough. Sure, we may spout wild dreams — I have multiple friends who’ve announced that “I want to be Oprah one day!” But when it comes to making concrete plans to actualize that, we get timid. We also live in terror that our plans may change. What if I’m wrong? What if it doesn’t work out?

The truth is, none of us has perfect information. Over time and through experience, you may well learn new things about yourself and your skills and preferences, or about the business. You certainly don’t have to hew to the same plan for seven years, no matter what. But engaging in long-term planning enables you to think big, and adapt where necessary.

“I decided about five years ago that when I retire, I want to live in a cabin on a lake in a nice town and do part-time coaching,” Samantha Fowlds told me. She’s a Canadian executive and a member of the Recognized Expert course and community I run for professionals who are looking to grow their platform and make a bigger impact. “I realized that if I want that dream to come true in 20 years, then I have to start now so I will have a solid foundation. So three years ago, I earned my professional coaching designation and now I take clients from time to time as I pursue my day job.”

Unlike Samantha, most people never think that far ahead. They want something now, and get angry or frustrated when it doesn’t immediately manifest. But the good things, of course, are ones you have to plan for — and work for.

At the end of the day, what becoming a long-term thinker most requires is character.

It’s the courage to carve your own path, without the reassurance of doing exactly what everyone else in the crowd is.

It’s the willingness to look like a failure — sometimes for long periods — because it takes time for results to show.

And it’s the strength to endure and persist, even when you yourself aren’t sure how it’s going to turn out.

Three habits to master long-term thinking

There are three habits of mind especially worth cultivating on your journey as a long-term thinker.

Independence. At its heart, long-term thinking is about staying true to yourself and your vision. In our society, there’s so much pressure toward short-term people-pleasing: saying yes to one more commitment because you don’t want to let someone down, or taking the “great job” that everyone else admires, but that leaves you feeling dead inside.

When you act for the long term, it can be quite a while before that pays off — and if you’re looking outside for validation, the wait can be devastating. Instead, to become fearless long-term thinkers, we need an internal compass that says: I’m willing to place my bet regardless of what others think, and I’m willing to do the work.

Curiosity. Some people are content to live their lives according to the roadmap that others have laid out for them, never questioning or pondering alternatives. But for many of us, a lifetime of coloring inside the lines can feel hollow — especially if our interests don’t align perfectly with what society valorizes. We may not know the exact right path for ourselves (who does, at first?), but one quality that can lead us to it is curiosity. By watching closely how we choose to spend our free time and understanding whom and what we find most fascinating, we can pick up clues about what lights us up — and where, eventually, we can begin to make our contribution.

Resilience. Doing something new, something unique, is by definition experimental. You have no idea if it’ll work or not — and oftentimes, it won’t. Too many of us experience rejection or failure and immediately recoil, assuming that the editor who turned us down was the definitive arbiter of taste, or that the university that rejected us obviously knew what they were doing. But that’s simply not true.

Chance, luck, and random individual preference play a massive role in how situations play out.

If 100 people reject your work, that’s a pretty clear message.

But one or two or 10? You haven’t even gotten started.

Becoming a long-term thinker requires a substratum of resilience, because it’s rare that anything works out the first time, or in the way you originally envisioned it.

You need to have a Plan B (or C, or D, or E, or F) in your back pocket, and the resilience to say: “Well, that didn’t work — so let’s try something else.” The number of at-bats is the crucial variable in your success.

We all have the capability to hone our skills, develop new techniques, and become better long-term thinkers.

In the short term, what gets you accolades — from family, from peers, from social media — is doing what’s predictable. The stable job, the beach vacation, the nice new car.

It’s easy to get swept along.

No one ever gives you credit for doing what’s slow and hard and invisible. Sweating out that book chapter, doing that colleague a favor, writing that newsletter.

But we can’t just optimize for the short-term and assume that will automatically translate into long-term success. We have to be willing to do hard, laborious, ungratifying things today — the kind of things that make little sense in the short term — so we can enjoy exponential results in the future.

We have to be willing to be patient.

Not patient in a passive, “let things happen to you” way, but actively and vigorously patient: willing to deny yourself the easy path so you can do what’s meaningful.

The results won’t be visible tomorrow, when the difference may be imperceptible.

But it will be in five or ten or 30 years, when you’ve created the future you’ve always wanted. Big goals often seem — and frankly, are — impossible in the short term. But with small, methodical steps, almost anything is attainable.

Dorie Clark is a marketing strategy consultant who teaches at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business and has been named one of the Top 50 business thinkers in the world by Thinkers50. She is the author of The Long Game, Entrepreneurial You, Reinventing You, and Stand Out. You can receive her free Long Game strategic thinking self-assessment.