Friday essay: the erotic art of Ancient Greece and Rome

In our sexual histories series, authors explore changing sexual mores from antiquity to today.

Rarely does L.P. Hartley’s dictum that “the past is a foreign country” hold more firmly than in the area of sexuality in classical art. Erotic images and depictions of genitalia, the phallus in particular, were incredibly popular motifs across a wide range of media in ancient Greece and Rome.

Simply put, sex is everywhere in Greek and Roman art. Explicit sexual representations were common on Athenian black-figure and red-figure vases of the sixth and fifth centuries BC. They are often eye-openingly confronting in nature.

The Romans too were surrounded by sex. The phallus, sculpted in bronze as tintinnabula (wind chimes), were commonly found in the gardens of the houses of Pompeii, and sculpted in relief on wall panels, such as the famous one from a Roman bakery telling us hic habitat felicitas (“here dwells happiness”).

However these classical images of erotic acts and genitalia reflect more than a sex obsessed culture. The depictions of sexuality and sexual activities in classical art seem to have had a wide variety of uses. And our interpretations of these images – often censorious in modern times – reveal much about our own attitudes to sex.

Modern responses

When the collection of antiquities first began in earnest in the 17th and 18th centuries, the openness of ancient eroticism puzzled and troubled Enlightenment audiences. This bewilderment only intensified after excavations began at the rediscovered Roman towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

The Gabinetto Segreto (the so-called “Secret Cabinet”) of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli best typifies the modern response to classical sexuality in art – repression and suppression.

The secret cabinet was founded in 1819, when Francis I, King of Naples, visited the museum with his wife and young daughter. Shocked by the explicit imagery, he ordered all items of a sexual nature be removed from view and locked in the cabinet. Access would be restricted to scholars, of “mature age and respected morals”. That was, male scholars only.

In Pompeii itself, where explicit material such as the wallpaintings of the brothel was retained in situ, metal shutters were installed. These shutters restricted access to only male tourists willing to pay additional fees, until as recently as the 1960s.

Of course, the secrecy of the collection in the cabinet only increased its fame, even if access was at times difficult. John Murray’s Handbook to South Italy and Naples (1853) sanctimoniously states that permission was exceedingly difficult to obtain:

Very few therefore have seen the collection; and those who have, are said to have no desire to repeat their visit.

The cabinet was not opened to the general public until 2000 (despite protests by the Catholic Church). Since 2005, the collection has been displayed in a separate room; the objects have still not been reunited with contemporary non-sexual artefacts as they were in antiquity.

Literature also felt the wrath of the censors, with works such as Aristophanes’ plays mistranslated to obscure their “offensive” sexual and scatalogical references. Lest we try to claim any moral and liberal superiority in the 21st century, the infamous marble sculptural depiction of Pan copulating with a goat from the collection still shocks modern audiences.

The censorship of ancient sexuality is perhaps best typified by the long tradition of removing genitals from classical sculpture.

The Vatican Museum in particular (but not exclusively) was famed for altering classical art for the sake of contemporary morals and sensibilities. The application of carved and cast fig leaves to cover the genitalia was common, if incongruous.

It also indicated a modern willingness to associate nudity with sexuality, which would have puzzled an ancient audience, for whom the body’s physical form was in itself regarded as perfection. So have we been misreading ancient sexuality all this time? Well, yes.

Ancient porn?

It is difficult to tell to what extent ancient audiences used explicit erotic imagery for arousal. Certainly, the erotic scenes that were popular on vessels would have given the Athenian parties a titillating atmosphere as wine was consumed.

These types of scenes are especially popular on the kylix, or wine-cup, particularly within the tondo (central panel of the cup). Hetairai (courtesans) and pornai (prostitutes) may well have attended the same symposia, so the scenes may have been used as a stimuli.

Painted erotica was replaced by moulded depictions in the later Greek and Roman eras, but the use must have been similar, and the association of sex with drinking is strong in this series.

The application of sexual scenes to oil lamps by the Romans is perhaps the most likely scenario where the object was actually used within the setting of love-making. Erotica is common on mould-made lamps.

The phallus and fertility

Although female nudity was not uncommon (particularly in association with the goddess Aphrodite), phallic symbolism was at the centre of much classical art.

The phallus would often be depicted on Hermes, Pan, Priapus or similar deities across various art forms. Rather than being seen as erotic, its symbolism here was often associated with protection, fertility and even healing. We have already seen the phallus used in a range of domestic and commercial contexts in Pompeii, a clear reflection of its protective properties.

A herm was a stone sculpture with a head (usually of Hermes) above a rectangular pillar, upon which male genitals were carved. These blocks were positioned at borders and boundaries for protection, and were so highly valued that in 415 BC when the hermai of Athens were vandalised prior to the departure of the Athenian fleet many believed this would threaten the success of the naval mission.

A famous fresco from the House of the Vetti in Pompeii shows Priapus, a minor deity and guardian of livestock, plants and gardens. He has a massive penis, holds a bag of coins, and has a bowl of fruit at his feet. As researcher Claudia Moser writes, the image represents three kinds of prosperity: growth (the large member), fertility (the fruit), and affluence (the bag of money).

It is worth noting that even a casual glance at classical sculptures in a museum will reveal that the penis on marble depictions of nude gods and heroes is often quite small. Classical cultural ideals valued a smaller penis over a larger, often to the surprise of modern audiences.

All representations of large penises in classical art are associated with lustfulness and foolishness. Priapus was so despised by the other gods he was thrown off Mt Olympus. Bigger was not better for the Greeks and Romans.

Myths and sex

Classical mythology is based upon sex: myths abound with stories of incest, intermarriage, polygamy and adultery, so artistic depictions of mythology were bound to depict these sometimes explicit tales. Zeus’s cavalier attitude towards female consent within these myths (among many examples, he raped Leda in the guise of a swan and Danae while disguised as the rain) reinforced misogynistic ideas of male domination and female subservience.

A mosaic depicting Leda and the swan, circa third century AD, from the Sanctuary of Aphrodite, Palea Paphos; now in the Cyprus Museum, Nicosia.Wikimedia

The phallus was also highlighted in depictions of Dionysiac revelry. Dionysos, the Greek god of wine, theatre and transformation was highly sexualised, as were his followers – the male satyrs and female maenads, and their depiction on wine vessels is not surprising.

Satyrs were half-men, half-goats. Somewhat comic, yet also tragic to a degree, they were inveterate masturbators and party animals with an appetite for dancing, wine and women. Indeed the word satyriasis has survived today, classified in the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD) as a form of male hypersexuality, alongside the female form, nymphomania.

The intention of the ithyphallic (erect) satyrs is clear in their appearance on vases (even if they rarely caught the maenads they were chasing); at the same time their massive erect penises are indicative of the “beastliness” and grotesque ugliness of a large penis as opposed to the classical ideal of male beauty represented by a smaller one.

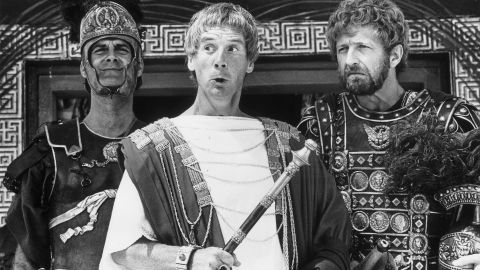

Actors who performed in satyr plays during dramatic festivals took to the stage and orchestra with fake phallus costumes to indicate that they were not humans, but these mythical beasts of Dionysus.

Early collectors of classical art were shocked to discover that the Greeks and Romans they so admired were earthy humans too with a range of sexual needs and desires. But in emphasising the sexual aspects of this art they underplayed the non-sexual role of phallic symbols.

Craig Barker, Education Manager, Sydney University Museums, University of Sydney

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.