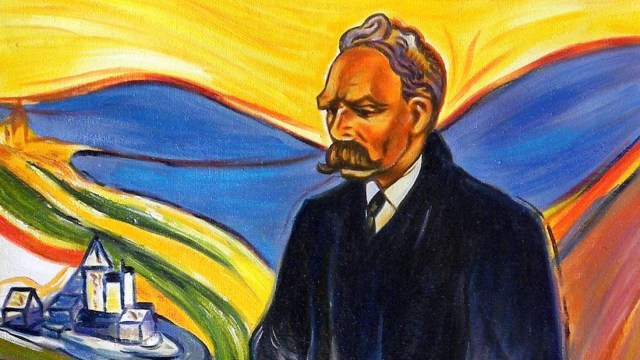

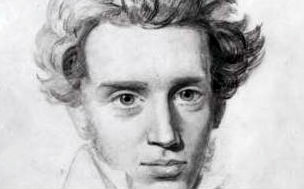

God’s Answer to Nietzsche, the Philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard.

Existentialism remains one of the more popular philosophies for the layperson to read about, consider, and study. The questions that it asks and the problems it confronts, ones of free will, anxiety, and the search for meaning; are ones we all face in our daily lives. While the solutions it offers may not work for everyone, existentialism can have a particularly large blind spot when it tries to provide answers for the religious.

Think of it, Nietzsche declared that God was dead, Sartre, Camus, and Beauvoir were all atheists, and the related philosophy of Nihilism also denies God’s existence. For the religious individual who seeks extra comfort from existential dread and the perspective of the existentialists on the problems of modern life, good answers can be hard to come by.

But there is an Existentialist who made Christianity one of the core principles of his thought. The founder of existentialism, Søren Kierkegaard.

Kierkegaard was a Danish philosopher born to a wealthy family in Copenhagen in the early 19th century. He was a prolific writer who often used pseudonyms to explore alternative perspectives. His work covers all of the areas of existential thought; anxiety, absurdity, authenticity, despair, the search for meaning, and individualism. However, unlike his atheistic successors, he places his faith in the center of the solutions to the problems of human life. Just as the death of God was key for Nietzsche, the need for God was just as important to Kierkegaard. Here are some of his insights:

On finding meaning

Kierkegaard agrees that life can be absurd and that meaning could be hard to come by. As opposed to Nietzsche, who said the death of God caused this, Søren argued that, in the present age, meaning is sucked out of concepts by abstraction and a tendency to view things with too much rationality. He lamented that he lived in an age where humans were increasingly viewed as generalizations, where the passionate man was seen as intemperate, and where most people simply went along.

He cries out for us to live passionately, and worry more about the problem of living life than trying to fit the social order. His philosophy is all about living this way, even to the point where an outside viewer will be unable to understand your motivation.

Kierkegaard also discovered a point that was hammered in by latter existentialists; reason and science can tell you a lot of things, but they cannot give something value or meaning. You have to do that. Meaning, value, and purpose cannot be reduced to quantifiable elements, it is up to the individual acting on their own to decide what the meaning of their life is going to be. His favored solution for finding meaning is to look to God and make a leap of faith. That alone, he argued, could both offer us meaning and properly balance us as people.

Pictured, the building blocks of life. Not pictured, the building blocks of the meaning of life.

On living with freedom

We must face the world as individuals, so Søren tells us. However, to fully be ourselves he posits that a person must recognize the “power that constituted it”. We are given the moral imperative to discover and live as ourselves, and God is a key part of that imperative. Every day, we are presented with facts of life and possibilities, and we must make choices. To not choose is also an option, but a poor one. To avoid becoming ourselves is to be in despair, which, for Kierkegaard, is to be in sin.

He warns us also of the anxiety that comes with choosing the path of our lives. While we must choose, we can never be sure that we choose correctly, as “Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.” In the same way, we have endless possibilities before us, except for those lives we chose not to have. He articulates the anxiety of having to choose to not live out some possibilities magnificently, “If you marry, you will regret it; if you do not marry, you will also regret it; if you marry or do not marry, you will regret both; Laugh at the world’s follies, you will regret it, weep over them, you will also regret that; laugh at the world’s follies or weep over them, you will regret both….”

Kierkegaard says they will live to regret it, no matter what happens.

Like Nietzsche, Kierkegaard also saw the potential use of “isms” to solve the problem of meaning in our lives. Søren focuses on the idea of an “ethical” life as an escape from deciding on meaning for yourself. By choosing a social or ethical system to latch onto we can find meaning in our relation to it; rather than by ourselves. He sees this as a possibility for many people, but not as the ideal solution to our problems.

One of his solutions to the problem of meaning was a Christian variant of the super-individualist Ubermensch; before Nietzsche had invented it.The Knight of Faith is an individual who has moved beyond relying on external rationality or “isms” for the justification of their lives and fully dedicated themselves to a higher calling. This calling is God in the case of Kierkegaard’s examples of Abraham and Mary.

They understand that the demands of God might be unethical, as the demand that Abraham kill his son was. However, they carry on past ethical concerns anyway, as to be a Knight of Faith is to be- to steal a phrase from Nietzsche- beyond good and evil.*

The benefits of Existentialism don’t have to be utterly separated from the Christian notion of God. Likewise, Kierkegaard’s insights do not require a dedication to Christianity to be used. He argued that the “passionate pagan” who prayed to a false idol was living better than the Christian who was worshiping out of mere habit. Even for those of us who are not Christians, it is possible to understand a little more about ourselves and the problems we all face as humans by considering the worldview of Søren Kierkegaard. A fantastic introduction to his ideas can be seen here.

*-To those of you who see a potential problem here, Kierkegaard notes in the book Fear and Tremblingthat some method must be used to determine who is a Knight of Faith and who is just a lunatic. Likewise, while the Knights could be divinely inspired to do horrible and bizarre things (like sacrificing children or inventing circumcision) by religious fervor, Søren posits that the typical Knight would be rather reserved and that we might never hear about them. Debate continues on if that answer is sufficient.