The Cult of ‘Deal or No Deal’

I’ve always been fascinated by the continuing global popularity of the hit British TV show Deal or No Deal, which is essentially a drawn out weekly recital of the Monty Hall Problem. Somehow the show created by Dutch producer Endemol is phenomenally successful despite consisting of nothing but sheer guesswork.

For the uninitiated, in every single episode the very same thing happens. A contestant spends half an hour guessing whether a box has a colossal amount of money in it (a million dollars in the U.S. version), eliminating other boxes in the process by guessing randomly, while the show’s host suggests the guesses are somehow reliably informed by the contestant’s feelings. Periodically, a “banker” offers to buy the contestant’s box that may or may not contain the jackpot. Over the course of the last decade, well over 2000 episodes have been broadcast in over 50 countries from Albania to America.

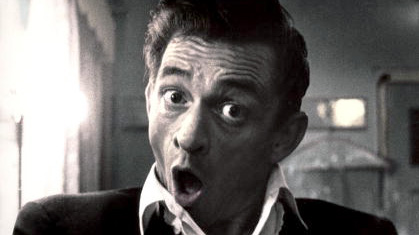

What is the attraction in watching a show that consists of nothing but uninformed speculation? To me, this sounds like not only a nightmare, but also a pointless nightmare. Yet somehow the show’s host, participants, and presumably the show’s viewers, never fail to be whipped up into an absolute frenzy, week after week. For the show’s regulars, the concept never gets old. Perhaps the show taps into a kind of magical thinking that many people are predisposed to, making the show uniquely compelling.

I recently stumbled upon a surprisingly eye-opening decade-old investigation in which writer Jon Ronson spent time as a fly-on-the-wall inside the filming of the British version of the show. Ronson makes an astute observation that partly explains why the British version of the show, unlike the American version which was canned years ago, is so insanely successful. The atmosphere in which the show is produced is very similar to the conditions inside a cult:

“When Endemol developed the format for British television, they came up with a brilliant idea. In other countries, such as the U.S., the people behind the boxes, the box-openers, are professional models, former Playboy centrefolds, etc. They all wear identical showgirl costumes. UK Endemol’s brilliant idea was to make the box-openers fellow contestants — players-to-be. This means they’re all sequestered away together at a hotel in Bristol, sometimes for weeks on end, away from the anchor of their homes, while they await their chance to get out from behind the boxes and become the main player. Consequently, an intense group bond forms. Late at night in the hotel, tiny things become huge things. Emotions are heightened. And in the morning, when filming begins, you can feel the drama in the winces and the cheers and the looks of love and hate that pass between the contestants.

According to the Cult Information Centre’s pamphlet Cults: A Practical Guide, cult leaders routinely employ 26 skillful techniques to keep their followers under their spell. One of the main ones is “Isolation: inducing loss of reality by physical separation from family, friends, society, and rational references.”

Endemol, which also makes Big Brother, realises that isolation doesn’t only produce good cults, but also produces good television.”

Ronson’s description of the paranoia and superstition that is whipped up among the contestants while they stay together in a hotel awaiting filming, is an excellent read. It seems however that the superstition that is the core element of the show does not end in the studio. The flagship show’s British host Noel Edmonds is in fact a deep believer in a smorgasbord of bizarre ideas.

Edmonds recently claimed that “electrosmog,” also known as WiFi, is “as bad as Ebola, climate change, and AIDS combined.” Obviously this is total nonsense; WiFi is harmless. A little more digging on Noel Edmonds unveils yet more odd ideas such as the belief he is visited by orbs of spiritual energy, and that writing down wishes makes them come true, suggesting his ridiculous superstitious comments throughout the show are actually not an act.

At this point, you might be quite reasonably saying to yourself, “OK, this Noel Edmonds fellow is clearly a crackpot; where are you going with this?” I find this case a perfect example of the side effects of magical thinking. Research has shown that if someone accepts any one conspiracy theory, they are far more likely to believe in a large number of other unrelated conspiracy theories and unfounded beliefs. So next time you turn on the TV and see an episode of Deal or No Deal is playing, perhaps take a moment to consider whether this type of magical thinking is something you might occasionally be guilty of yourself. Be careful, the slope is a slippery one.

Follow Simon Oxenham on Twitter, Facebook, Google+, RSS, or join the mailing list to get each week’s post straight to your inbox. Image Credit: Getty/NBC