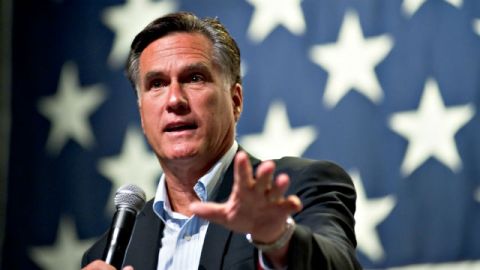

The Absurdity of Mitt Romney’s Education Plan

Mitt Romney’s plan for education, released last week, sounds a number of predictable conservative themes: union bashing, continued reliance on standardized testing, expansion of charter schools and reform or elimination of teacher tenure.

Romney has a few new ideas as well, none of them good. Here’s the doozy:

A Romney Administration will work with Congress to overhaul Title I and IDEA so that low-income and special-needs students can choose which school to attend and bring their funding with them. The choices offered to students under this policy will include any district or public charter school in the state, as well as private schools if permitted by state law.

What’s wrong with a policy that puts federal dollars in individual parents’ hands to spend as they see fit?

1. There aren’t enough seats in the good schools to accommodate all comers.

Romney’s plan permits parents to redirect their kids to any school “in the state,” presumably putting an affirmative duty on every public or charter school in the state to accept kids from failing schools. This demand is impossible to fulfill. Good schools in most urban districts are already cramped for space. Some cannot even accommodate every child in their zone, let alone their district. How could they find a seat for every low-income student in the state seeking a better education? Charter schools turn away thousands as well. Simply willing kids into at-capacity schools doesn’t make it happen. This is a one-way busing policy, ludicrous on its face.

2. Middle-class families get the shaft.

Even if every low-income student in a bad school somehow was able to enroll in her dream school, Romney’s plan does nothing — nothing — for children whose family income hovers above the poverty line. If you’re middle class and your child is in a terrible school, you’re stuck. Theoretically, you could apply to a charter school and enter the admissions lottery, but with all of the low-income students vying for those seats, you’d be out of luck.

3. Public schools are allowed to rot on the vine.

Maybe worst of all, Romney’s plan invests no new ideas in the public school system. It transfers funds from public schools to privately run charter schools and goes the extra mile of diverting money from the public system to low-income parents for “supplemental tutoring or digital courses from state-approved private providers.” That’s right: school budgets will shrink so that the federal government can send checks to parents to hire private tutors and buy online courses for their children. This is a prescription for ending public education as we know it. While Romney hails charter schools for their “dramatically positive effects while working with some of the nation’s most disadvantaged students,” he derides public schools as “local education monopolies.”

It is true that charter schools have shown some positive results in closing the achievement gap, but recent data reveals that charters keep test score results artificially high by kicking out low-performing students and their graduates have a hard time completing college. I suspect the path to college commencement is hampered by the racially homogenous experience in most charter schools. If the failure of public education is the “civil rights issue of our era,” as Romney said last week, it seems perverse to herald highly segregated schools as the answer.

Another change Romney seeks is problematic as well. While retaining its standards-based approach to measuring student outcomes, Romney seeks to roll back the punitive side of President Bush’s No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) from 2002 and replace it with greater transparency about school quality. Here is how the campaign puts it in its white paper, “A Chance for Every Child”:

The school interventions required by NCLB will be replaced by a requirement that states provide parents and other citizens far greater transparency about results. In particular, states will be required to provide report cards that evaluate schools and districts on an A through F or similar scale based primarily on their contribution to achievement growth.

Report cards for schools may sound like a good idea, but there are significant, maybe intractable problems associated with these types of reductive assessments, as the farce of New York City’s progress report system (undertaken in 2007) demonstrates. Here is Michael Winerip’s take in the New York Times earlier this month:

Public School 30 and Public School 179 are about as alike as two schools can be. They are two blocks apart in the South Bronx. Both are 98 percent black and Latino. At P.S. 30, 97 percent of the children qualify for subsidized lunches; at P.S. 179, 93 percent.

During city quality reviews — when Education Department officials make on-site inspections — both scored “proficient.” The two have received identical grades for “school environment,” a rating that includes attendance and a survey of parents’, teachers’ and students’ opinions of a school….

And yet, when the department calculated the most recent progress report grades, P.S. 30 received an A. And P.S. 179 received an F. Is P.S. 30 among the best schools in the city and P.S. 179 among the worst? Very hard to know. How much can the city’s report cards be trusted? Also very hard to know.

New York City’s school officials stand by their progress reports, and an independent watchdog group recently praised certain aspects of the reports while noting their flaws.

But even if the perfect report card methodology could be found, there is still the question of what to do with the results. If your children qualify for Title I funds and attend a school that gets a D or an F, Romney consoles you with his exit option: leave the school and send your kids to any school you like, anywhere in the state! Beyond its unfairness to middle class families and sheer unworkability, this offer is hardly the path to solving our public education crisis.

Photo credit: Christopher Halloran / Shutterstock.com

Follow Steven Mazie on Twitter: @stevenmazie