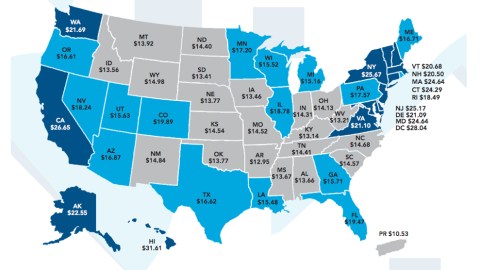

Report: A minimum-wage job can’t pay the rent anywhere in U.S.

A full-time minimum wage isn’t enough money to rent an averagely priced one-bedroom home anywhere in the U.S., according to an annual report issued this week by the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

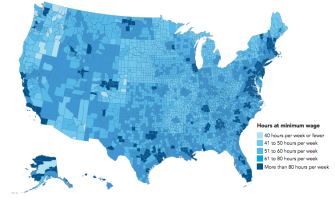

The report illustrates stark realities facing some low-income workers in the U.S. For instance, someone working full time at $7.25 per hour, the federal minimum wage, would need to put in 122 hours a week to afford a modest two-bedroom rental home, priced at the national average fair market rent of $1,149, and still have money left for other necessities.

(It’s worth noting that researchers used a budgeting standard that says people shouldn’t spend more than 30 percent of gross income on rent and utilities. Not everyone agrees that this standard, which stems from the New Deal era, is useful.)

“The same worker needs to work 99 hours per week for all 52 weeks of the year, or approximately two and a half full-time jobs, to afford a one-bedroom home at the national average fair market rent,” the report reads. “In no state, metropolitan area, or county can a worker earning the federal minimum wage or prevailing state minimum wage afford a two-bedroom rental home at fair market rent by working a standard 40-hour week.”

Here’s a map of the U.S. from the report showing how many hours you’d have to work at the $7.25 wage to afford a one-bedroom rental home at fair market rent.

The costliest state is Hawaii, where the minimum wage recently raised to $10.10 but you’d need to earn about $75,000 a year to rent a modest two-bedroom home. The cheapest housing is in Arkansas, a state with an $8.50 minimum wage, where you’d still need to make about $29,000 a year to afford a two-bedroom rental at fair market price.

One economic force driving low-income people out of housing is a process known as filtering, which happens when older properties become more affordable over time. But filtering typically doesn’t produce enough housing for extremely low-income renters, the report said, and at a certain point it makes more sense for landlords to redevelop units so they can charge higher rents.

“Absent public subsidy, the private market fails to provide sufficient housing affordable to the lowest income households,” the report reads. “At the same time, three out of four low income households in need of housing assistance are denied federal help due to chronic underfunding (Fischer & Sard, 2017). The net result is a national shortage of 7.2 million rental homes affordable and available to the lowest income renters (NLIHC, 2018b). No state or major metropolitan area has an adequate supply.”

Since the 1970s, wages have been mostly stagnant for Americans in the middle and lower classes even as productivity has risen. Why?

It’s a complex question, but, as Jay Shambaugh and Ryan Nunn wrote for the Harvard Business Review, some key factors include: workers receiving a diminishing proportion of income over recent decades, globalization and technological advancement pushing out low-wage workers, and firm collusion and domestic policies disadvantaging workers’ bargaining power.

The data on wage stagnation and income disparities among U.S workers is clear, but how or whether to remedy the situation with policy remain open questions.

Here’s where the National Low Income Housing Coalition seems to stand on policy, as seen through part of the report’s foreword, which was authored by Senator Bernie Sanders:

“We must extend rental assistance and other housing benefits to the millions of low income families who need help to make ends meet, but who have been turned away because Congress refuses to fund these programs at the level needed. We must stem the rising tide of evictions and invest in innovative strategies aimed at eliminating homelessness. And we must start to close the housing wage gap by raising the minimum wage to at least $15 an hour – so that no full-time worker lives in poverty.”