GUI: Some doubted, even Woz

- GUIs are literally everywhere — from your iPhone to your car’s audio system.

- However, they were once seen as a strange deviation from command line-based computing.

- In the 1990s, GUIs were thought by some to be useless at best and a threat to creativity at worst.

Today, most everyone interacts with a computer via a graphical user interface (GUI) — that is, that flashy, interactive display with icons. We have simply accepted this with the same indifference we have toward things like refrigerators and washing machines. But we shouldn’t take it for granted. Before this ubiquitous interface, there was the command line.

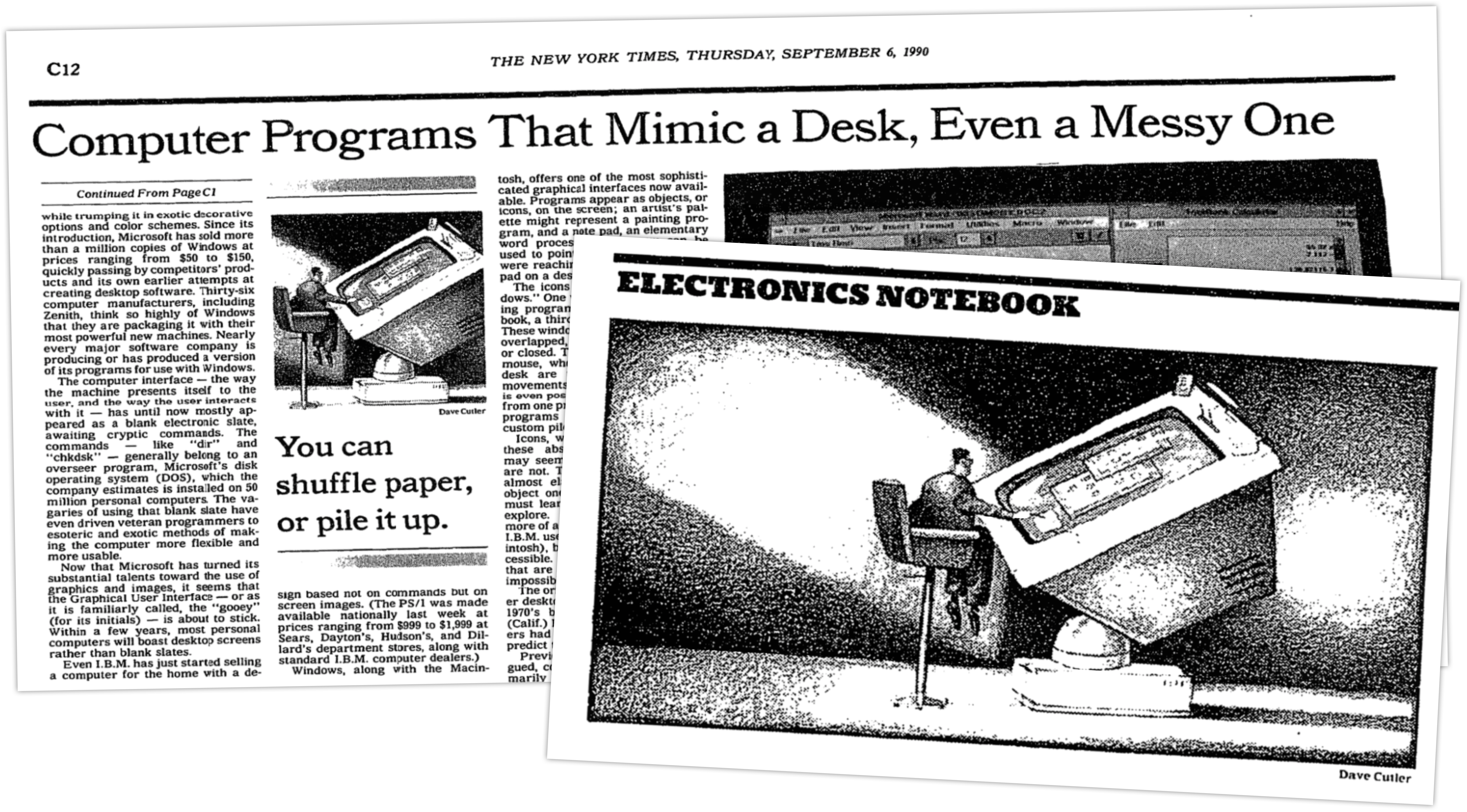

When the GUI first emerged, it was seen as a strange new innovation, and it elicited both awe and concern. A 1990 article from the New York Times, titled “Computers That Mimic Desks,” described a new paradigm of computing, in which “the text that used to glow with amber or green can now appear on the screen as if it has just been typeset.” Miraculous! What we now know as a word processor (like Microsoft Word or Google Docs) was heralded as a technological marvel.

The piece continued, describing this strange new future: “A spreadsheet can appear the same way, as if printed on white bond. These electronic ‘Papers’ can be piled up on the screen, shuffled about, cut and pasted, filed or destroyed.”

The idea of a virtual world, just below a sheet of glass — one where you can travel back in time (undo), infinitely clone anything (copy and paste), or have a limitless supply of ink (pixels) that could magically change form on a whim (fonts) — was as bizarre then as the prospect of the Metaverse is today. In many ways, and especially with the advent of the internet, GUIs were a 2D Metaverse — a Metaverse that you are in right now.

Even Woz doubted

The Macintosh was the first consumer computer with a graphical user interface, released in 1984. It caught the world’s attention with a “bizarre” superbowl advert, as one newspaper put it. The Macintosh, compared to other computers at the time, seemed childish, with the icons being compared to “cartoons.” But it lacked the seriousness of computers of the time. It sat, as Steve Jobs famously put it, at the intersection of technology and the liberal arts, where other systems remained in a sterile cul-de-sac of technology.

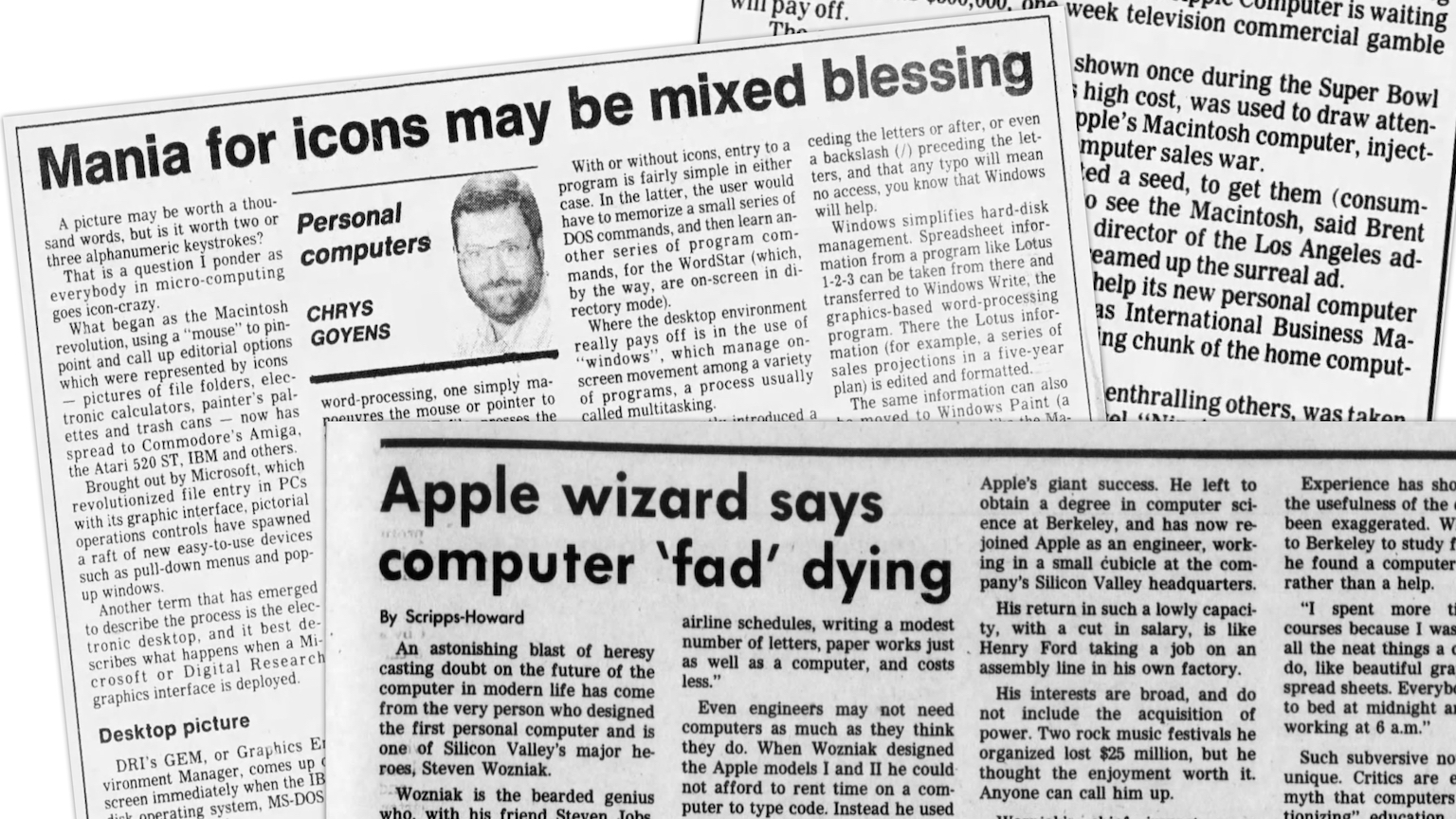

Some wondered if GUIs were more of an aesthetic leap than a functional one, such as Canadian writer Chrys Goyens, who said of word processing: “The graphic-interface gain is not quite that overwhelming.”

Even Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak had voiced his doubts. In 1985, he called the personal computer — along with video games — a “dying fad,” casting doubt on the notion of a general computing device for every person. He claimed that: “For most personal tasks, such as balancing a checkbook, consulting airline schedules, writing a modest number of letters, paper works just as well as a computer, and costs less.” He left Apple the following year, reportedly out of frustration with how much attention was being given to the Macintosh development over the Apple II.

The GUI made students lazy

Indifference to GUIs turned to outright hostility in 1990, after a study was published by Marcia Peoples Halio, an English professor at the University of Delaware. Appearing in the journal Academic Computing, the paper titled “Student Writing: Can the Machine Maim the Message?” claimed that students who used a GUI-based Macintosh turned in poorer work than those using a command line system. While some called for more research to be conducted on this worrying find, other academics criticized the study for being unscientific and failing to use control groups. Apple was eager to point this out too. Though Halio admitted the study had flaws, she insisted, “Giving a machine like (the Macintosh) to someone before they can write well is sort of like giving a sports car to a 16-year-old with a new driver’s license.”

Regardless, the findings got national and international press coverage, starting with the San Jose Mercury News, Apple’s hometown paper. Hailo was quoted from the paper saying, “Never before in 12 years of teaching had I seen such a sloppy bunch of papers.” The paper itself, which fittingly isn’t available online, was summarized by the newspaper thusly: “The same icons, mouse, fonts and graphics that make the machine easy to use may well turn off the brain’s creative-writing abilities.”

A Los Angeles Times piece critical of the study still admitted that “the idea that our minds are somehow warped by our word processors is too intriguing to be ignored.” The Chicago Tribune syndicated a column the following year co-written by Brit Hume (yes that one), which correctly concluded the debate was moot since GUIs would soon be everywhere. Another LA Times piece was less balanced, beginning (half-jokingly): “Well, they’ve finally demonstrated something that I’ve known all along: that computers and word processors are instruments of the devil and should be exorcized at the first opportunity.”

Plato would have hated the GUI

After a brief mention in 1990, the New York Times wrote an entire article on the subject in 1992, a more critical take on its previous fawning over word processing and GUIs.

It used a few historical analogies, one a quote from 18th-century playwright Richard Sheridan, who critiqued his own use of a “quill processor” (a feather pen). The article also cited a previous 1985 Times column by Russell Baker, critiquing the command line-based word processing that was prevalent before GUIs became popular.

But the concerns keep going back in time. Concerns about command lines echoed those about typewriters from the early 1900s. And those? Well, they mimicked Plato’s concerns about the very act of writing itself from 370 BCE, when he said:

“If men learn this, it will implant forgetfulness in their souls. They will cease to exercise memory because they rely on that which is written, calling things to remembrance no longer from within themselves, but by means of external marks.”

Writing itself is technology

This is a great reminder that writing — even with a quill on parchment or chalk on slate — is technology. With brain-computer interfaces in rapid development, the prospect of typing with only our thoughts is on the horizon. And surely, this never-ending debate will begin again, stoking fears about the corrosive nature of technology on the art of writing.