Stockdale Paradox: Why confronting reality is vital to success

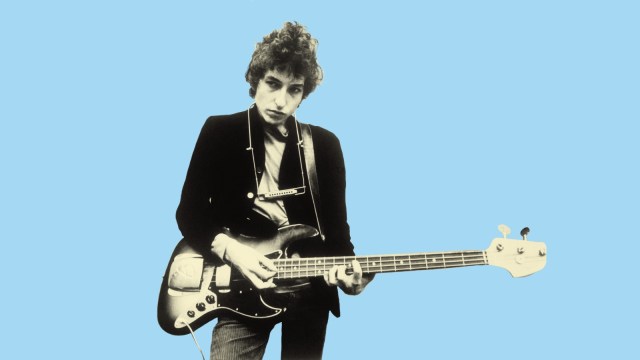

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

- The Stockdale Paradox is a concept that was popularized by Jim Collins in his book Good to Great.

- It was named after James Stockdale, former vice presidential candidate, naval officer, and Vietnam prisoner of war.

- The paradox describes the value and difficulty of striking a balance between realism and optimism.

We often find some of the greatest bits of wisdom in paradox. The difficulty in understanding a paradox comes from the fact that when it’s heard as a maxim in some kind of verbal form, it is contradictory and not intuitively grasped. Paradoxes are better understood through experience.

The Stockdale Paradox is one such concept that, at first glance, takes some linguistic mental jumping jacks to fully grasp. This paradox was first put forward in Jim Collin’s book Good to Great, a seminal corporate self-help and leadership book.

Author Jim Collins found a perfect example of this paradoxical concept in James Stockdale, former vice-presidential candidate, who, during the Vietnam War, was held captive as a prisoner of war for over seven years. He was one of the highest-ranking naval officers at the time.

During this horrific period, Stockdale was repeatedly tortured and had no reason to believe he’d make it out alive. Held in the clutches of the grim reality of his hell world, he found a way to stay alive by embracing both the harshness of his situation with a balance of healthy optimism.

Stockdale explained this idea as the following: “You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end — which you can never afford to lose — with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”

In the most simplest explanation of this paradox, it’s the idea of hoping for the best, but acknowledging and preparing for the worst.

What is the Stockdale Paradox?

Understanding the Stockdale Paradox can help you better confront the reality of tough situations while also maintaining faith that you’ll ultimately succeed. This contradictory way of thinking was the strength that led James through those trying years. Such paradoxical thinking, whether you consciously know it or not, has been one of the defining philosophies for great leaders making it through hardship and reaching their goals.

Whether it’s weathering through a torturous imprisonment in a POW camp or going through your own trials and tribulations, the Stockdale Paradox has merit as a way of thinking and acting for any trying times in a person’s life.

The inherent contradictory dichotomy in the paradox holds a great lesson for how to achieve success and overcome difficult obstacles. It also flies right in the face of unbridled optimists and those positivity peddlers whose advice pervades nearly every self-help book or guru spiel out there.

In a discussion with Collins for his book, Stockdale speaks about how the optimists fared in camp. The dialogue goes:

“Who didn’t make it out?”

“Oh, that’s easy,” he said. “The optimists.”

“The optimists? I don’t understand,” I said, now completely confused,

given what he’d said a hundred meters earlier.

“The optimists. Oh, they were the ones who said, ‘We’re going to be out by

Christmas.’ And Christmas would come, and Christmas would go. Then

they’d say,’We’re going to be out by Easter.’ And Easter would come, and

Easter would go. And then Thanksgiving, and then it would be Christmas

again. And they died of a broken heart.”

Applying the Stockdale Paradox to your daily life

We all want things to workout for ourselves. We want to be successful, happy, and have achieved something no matter how trivial or personal it may be. Reaching this state of accomplishment isn’t going to come just by positive visualization. That’s all well and good and it makes us feel nice. It’s why so many people like to listen to the endless screeds of “business gurus” and motivational shysters promising us the world if we only just learned to change our mindset.

Confronting the entire brevity of your situation is instrumental for success. There’s a bit of positive visualization in there, but it needs to be counterbalanced with the thought that you can utterly fail and to put it frankly – your current existence might be absolutely miserable and hopeless. But don’t lose faith, your wildest dreams just might come true. . . hence the paradox.

It’s not about choosing which side to take, but instead learning to embrace both feelings in opposition to one another and realize they’re necessary and interconnected.

Stockdale Paradox in business and hardship

On a higher level, and when it comes to business leadership and management, this duality helps to guard against the onslaught of disappointments that will hit you in the business world. Optimism may drive innovation, but that needs to be put in check to help ensure that you’re still on this plane of reality and not bumbling naively into something that can’t happen.

It’s a great mechanism to keep yourself grounded, but also entertain the idea of being incredibly successful in whatever pursuit you’re after.

The Stockdale Paradox can help out an organization assess a current situation and plan accordingly to tackle the challenges they come across. It enforces both the idea that you can be positive and believe you will overcome all difficulties while at the same time you are confronting the most brutal facts of your current situation. The latter is what turns people off, because it can be misconstrued as negative or overly pessimistic.

Similar ideas to the Stockdale Paradox

Yet, we’ll find again and again that it is this line of thought that fosters success even in the most dire and inhumane of situations. Viktor Frankl, psychotherapy and holocaust survivor, wrote in his book Man’s Search for Meaning that prisoners within Nazi concentration camps usually died around Christmas time. He believed that they had such a strong hope they’d be out by Christmas that they simply died of hopelessness when that didn’t turn out to be true.

Here is a passage from his book regarding this thought:

“The death rate in the week between Christmas, 1944, and New Year’s, 1945, increased in camp beyond all previous experience. In his opinion, the explanation for this increase did not lie in the harder working conditions or the deterioration of our food supplies or a change of wealth or new epidemics. It was simply that the majority of the prisoners had lived in the naive hope that they would be home again by Christmas. As the time drew near and there was no encouraging news, the prisoners lost courage and disappointment overcame them. This had a dangerous influence on their powers of resistance and a great number of them died.”

Frankl developed a concept he called “tragic optimism,” that is, an optimism in the face of tragedy. This idea has gone through many names and iterations throughout the years. In the Nietzschean worldview, it’s the idea that whatever doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. Tragic optimism is similar to the Stockdale Paradox, as they both express a paradoxical idea about acknowledging your current difficulties intermixed with a positive belief that in the end you will still triumph.