6 logical fallacies politicians often use—and how to guard yourself against them

Election season in the United States brings many things, some good and some bad. Among the things which we citizens must endure each time are poor arguments using logical fallacies. While bad arguments are far too common, many of them are easy to identify. With just a little knowledge and effort you can sniff out the faulty reasoning and avoid getting fooled.

Here are six logical fallacies that are commonly used in politics. Included are examples of how these fallacies are used and suggestions on how to avoid being taken in.

Ad Hominem

One of the most common and pettiest fallacies known to humanity. This fallacy occurs when the traits of the person holding a position are attacked rather than the merits of the argument they make. It can also be used against organizations or institutions.

Example

Mr. Jones’ tax plan isn’t worth considering. What could a person who works for the government know about taxes?

As you can see, no argument against the tax plan is given. All we have been told is something about one person who supports the idea. This says nothing about the merits or failings of the proposal.

How do I not get tricked?

The best way to get around this is to remain focused on the issues and not on the personalities of the people running for office. While some personality traits might be more desirable than others, the fact that a person has them or not has little bearing on the merits of the arguments they make.

Slippery Slope

A very slippery slope. (Getty Images)

A pervasive fallacy that regularly fools millions. This is the argument that if one action is taken another, absurd or undesirable, action will inevitably follow. Therefore, we ought to not take that first step.

Example

If we let women vote, the next thing you know we’ll let animals vote!

This argument can be hard to spot but always relies on the idea that one event will necessarily follow from another. The fallacy lies in that some actions are not connected by necessity but are presented as such.

How do I avoid getting tricked?

When you hear this setup, be sure to check that the second event is necessary. If it isn’t, the speaker is trying to fool you.

Remember, there has to be a logical reason that the next step must follow the first. In the above case, there is nothing that forces legislators to enfranchize dogs just because they enfranchize women; making it a fallacious argument.

Strawman Argument

A strawman (MIGUEL RIOPA/AFP/Getty Images)

Some arguments are so bad that nobody makes them. They could be pointed out as absurd just by saying what they are. The Strawman fallacy takes advantage of this. This fallacy occurs when another argument is exaggerated or presented bizarrely in an attempt to discredit it. Other times, a position that nobody holds will be presented as the one held by an opponent, and that position will be attacked in place of their actual one.

Example

Person One: I think people should eat fewer fatty hamburgers.

Person two: You don’t think people should eat meat? Are you trying to put farmers out of work? Trying to disrespect the culture and work of barbeque chiefs everywhere? You vegetarians and your moralizing, soon you’ll complain when people drink water!

As you can see, the second person misrepresented the point person one made and then attacked that point. By exaggerating the first person’s position, they have created a strawman which is easier to attack than the first person’s real stances. The original argument is ignored and not disproven.

How can I avoid getting fooled?

This fallacy relies on misrepresenting one argument and replacing it with another one. The simplest way to not be taken in is to study the first argument yourself, without the chance of an opposing candidate scrambling it.

False Dilemma

There are always more than two options. This fellow, for example, could choose to turn around and go back where they started.

We’ve all heard this fallacy before. We are given two options, one much worse than the other. It is then said or heavily implied that we must select the option that is the lesser evil. Potential third options are left out.

Example

The choice is simple; either we let dogs vote, or we’ll slide into a dictatorship!

As you might suppose, there are plenty of other options. Perhaps we can retain democracy without enfranchising animals, for example. The speaker, however, is trying to railroad you towards supporting a position they hold by only presenting two options.

How can I avoid getting tricked?

The simplest method for dealing with this fallacy is always to make sure that the options on the table are your only options. You should also pay attention when people say that the choice is simple, a false dilemma is probably close at hand.

Ad Populum

Also known as the bandwagon appeal, this is the false claim that what is popular is good. This fallacy is widespread and sometimes blatant. The famous “I like Ike” television commercials were nothing but this fallacy set to a snappy jingle.

Example

Everybody likes Mr. Jones! You should vote for him too!

This appeal to popularity suggests that the popular choice is the good one. When you hear this argument, you’re likely to hear more about how popular they are than what their qualifications are.

How do I avoid getting tricked?

The best defense against this trick is to focus on the qualifications of a candidate. An unqualified candidate who is popular is still a lousy candidate.

False Equivalence

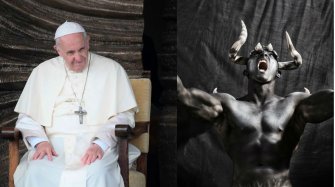

These two both have noses, does that make them morally equivalent? (FILIPPO MONTEFORTE/AFP/Getty Images/BigThink)

This fallacy is when two stances are presented as equivalent when they are not. During campaigns, you will often hear people comparing two candidates using this fallacy.

Example

Yes, Mr. Smith is a serial embezzler, but Mr. Jones once littered in the park. They’re practically the same!

Embezzlement is a serious crime while littering, while wrong, is poor manners at worst. The argument in the example, however, is that both offenses make the perpetrators equally bad. While this does mean that both people have done things they should not have, they are far from equally bad; especially if they are trying to be in charge of public funds.

How to avoid getting taken in

This fallacy is tricky, as it can only be used when there is a superficial similarity between two stances. However, as with the above example, looking a little more closely reveals that the positions are far from identical.

—