How to Innovate When You’re Not the Big Boss

A few years ago, Brad Anderson, then CEO of Best Buy, told me something both provocative and profound. We were discussing what he looked for in selecting someone for a C-suite level role. Among other skills, he wanted to find executives who had the wisdom to know when the organization needed to be fundamentally changed and shaken up — and when the organization needed time to incorporate prior changes.

Brad’s comment illustrates an important truth about succeeding to the executive level. Given the unrelenting pace of change surrounding organizations in virtually every industry, companies are looking for executives who know how to innovate and introduce change, not simply caretakers who can manage the status quo.

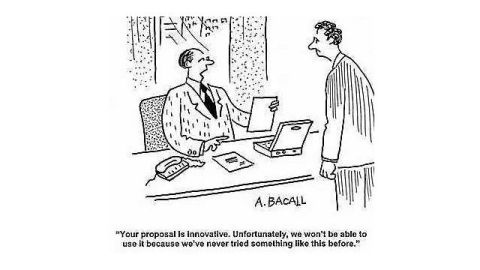

When ambitious managers one or two levels below the C-suitehear that they need to demonstrate the ability to lead innovation and change, this feedback typically triggers howls of protest, often preceded by “They won’t” or “They don’t.” Senior management doesn’t really encourage innovation, you’ll hear. “They won’t let me take risks.” “They don’t tolerate mistakes or failure.”

In most companies there’s more than a kernel of truth to these managers’ complaints. At the middle management level you typically don’t have the clout or resources required to make sweeping changes. Nonetheless, the dilemma remains. Senior-level decision makers in your company are looking for evidence that you can lead innovation and change; simply being a master of continuous improvement won’t cut it. Fortunately, demonstrating your skills in this area doesn’t demand that you singlehandedly develop a new breakthrough product or revise the company’s overall business model. Usually, if you search, there are opportunities in your current job and at your current level to display your ability to drive change, even if you are in a support function like finance or human resources.

Senior-level decision makers aren’t looking for someone at your level to make “roll the dice” bets that can have a significant negative impact on company performance. Rather, they’re interested in the quality of your ideas and how you shepherd them through the organization — whether it’s introducing a new organization design or revising a management process. So, look for opportunities in your current job to grow the business or change how things get done. Is the annual planning and budgeting system overly time-consuming and out of sync with the pace of the business? Is there a better way to identify and respond to the needs of customers? How can you reduce cost in one part of your organization — via centralization, automation, or outsourcing — in order to shift resources to more value-added activities?

As an example, consider Lynn Hollings, a mid-level manager who took the initiative to introduce change within her organization. Lynn headed up a product management unit for a large consumer products company. She, like a number of executives within the company, knew that a few major customers were becoming more powerful and demanding as their annual purchases from the company grew.

After conversations with a range of executives within her operating group, Lynn devised a plan to create customer-focused teams designed to meet the needs of a handful of key retail buyers. Each customer team included sales and sales support as well as staff aligned to the group’s product development units, in-store merchandising, finance, and logistics departments. The goal of each customer team was to partner with the major retailers and create highly customized approaches — in product, merchandising, delivery/inventory management, and billing and collection — all with the aim of creating customer loyalty and growing revenue.

In addition to selling the operating group president and other group executives on the concept, Lynn enlisted a number of people from across the corporate organization to help create the new organization structure and supporting systems. Although the effort involved a number of staff members, there was no question that Lynn was the key player guiding the initiative at every step along the way. As a result, she gained a reputation as an innovative manager who could drive change.

Keep in mind that in addition to the results of your proposed innovation, senior executives are looking for a series of personal skills and attributes that serve as a preview of coming attractions concerning your ability to lead change at the executive level. For example:

To advance to the executive level, it’s not necessary to be a creative genius like Steve Jobs. However, senior-level decision makers want to make sure that you have the leadership “gear” to introduce change when circumstances call for it. Without periodic innovation — in product, process, and organization — organizations tend to become rigid over time. That’s the real point of Brad Anderson’s message: that companies need to be stretched and challenged periodically to avoid complacency. And that demands leaders who know when to push the organizational envelop, even when all the t’s aren’t crossed and all the i’s dotted — as well as leaders who have the necessary tolerance for risk and the skills to lead an organization through change.

This article was originally published at HBR.org, where John Beeson is a regular contributor.