Do We Need An Ethics of Consciousness?

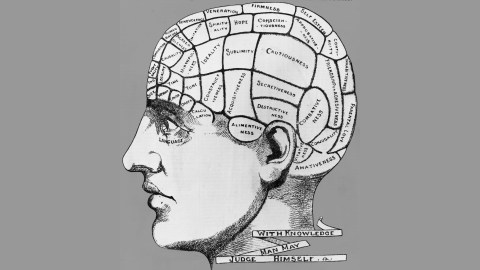

The struggle to define consciousness will likely remain for some time. While progress has been made in understanding the mechanisms behind consciousness, a seemingly limitless neuronal interaction makes discovering a point of origin challenging.

We know consciousness is body-dependent and requires a system-wide effort. There is most likely no ‘consciousness center’ in our brain, as there are regions for language and emotional processing, for example. As researchers uncover the role of more real estate in our nervous system, we’ll have a better idea of exactly how consciousness works, perhaps even why it evolved to the degree it has in humans.

As we make more headway, philosopher Thomas Metzinger believes we need an ethics of consciousness. In The Ego Tunnel, he employs the phenomenal self-model (PMS) as his central metaphor—phenomenal derived from philosophy, “what is known purely experientially, through the way in which things subjectively appear to you.”

This model allows humans to recognize themselves and others as a whole. We know; we know we know; we know that others know. Just as our brain maps our body, our mind maps our body moving through space. We are then able to proceed as part of a greater unit, helping to explain our successful and complex social groups.

Metzinger takes a refined stance on defining consciousness. His tunnel is the means by which we subjectively view reality. Thanks to transparency—we are unaware of how information reaches us—we still function and evolve. He writes,

We do not see the window but only the bird flying by. We do not see neurons firing away in our brain but only what they represent for us.

Instead of peering from the back of the machinery, consciousness sits at the front, like a lens attached to a camera. Our full awareness is only this lens; the camera body runs in the background, much like our own bodies. Transparency is so pervasive, in fact, no one recognizes the hardware at all; we believe what we see represents the total sum of what is there, front end to back end.

What sets human consciousness apart from other biologically evolved phenomena is that it makes a reality appear within itself. It creates inwardness; the life process has become aware of itself.

Consciousness, he writes, is “the presence of a world.” We are viewing the world through our singular lens, part of a “complex physical event—an activation pattern in your central nervous system.”

Such awareness is often perceived as a spiritual pursuit. Yet strip religion of metaphysics and what you have left are morals. Metzinger is no hardcore materialist; he offers chapters to out-of-body experiences and lucid dreaming. Mysticism is an illusion the brain plays on itself; a fascinating one, though an illusion nonetheless.

To combat such illusions, morals help structure societies. Besides, with many religious experiences replicable in laboratories (out-of-body experiences, transcendent sensations), focusing on how to alter consciousness is more valuable than bowing to prior dogmas. Metzinger writes that a number of substances—psilocybin, mescaline, ayahuasca—have allowed us to drastically alter what and how we see. In a neurochemical future, this will increase.

It already is, though dangerously; with synthetic cannabinoid compounds, for example. The war on drugs has been a dismal failure, but it’s only going to complicate reality further as home cooks concoct new formulas. Combined with the potential for AI, Metzinger concludes by asking a simple question: is an ethics of consciousness possible?

Just as today we can opt for breast enlargement, plastic surgery, or other types of body modification, we will soon be able to alter our neurochemistry in a controlled, finely tuned manner.

Few people take issue with drastically altering their parts. (Trust me, I live close to Beverly Hills.) For some reason, altering consciousness has long been an issue of contention. That’s changing; Metzinger wants to be ahead of the curve, not behind, as many drug and technology policies have been.

Speculating on what such an ethics would require, Metzinger invents three conditions for a desirable state of consciousness:

1. It should minimize the suffering in humans and all other beings capable of suffering.

2. It should ideally possess an epistemic potential (that is, it should have a component of insight and expanding knowledge).

3. It should have behavioral consequences that increase the probability of the occurrence of future valuable types of experience.

How we go about achieving these is open for debate. One avenue is meditation in high school, familiarizing students with the brain-body connection. Metzinger reminds us that the brain is part of the body. Dualistic philosophy has wreaked havoc; disconnecting the brain from our bodies creates wildly unrealistic and dangerous ideologies. Instead teach people from an early age how our nervous systems work so they can show empathy toward others as they mature.

Self-responsibility will also be an important hallmark of this new ethics. What we lack, Metzinger writes, “is not faith but knowledge.” Quit the grand proposals and focus on practical applications. Increase autonomy in the individual while decreasing manipulation through groupthink. Demystify consciousness via research and honesty and you’ll increase solidarity between cultures and with other species.

Metzinger concludes by contemplating dignity, which some fear we’ll lose if we admit we’re part of nature, not a species given the power to rule it. Clinging to these past notions, however, is where dignity is actually lost.

Dignity is the refusal to humiliate oneself by simply looking the other way or escaping to some metaphysical Disneyland.

Denial, irrationalism, and fundamentalism are the triad of dignity killers. It might take some time to agree upon a new ethics, but falling back on bad habits is not the way ahead. Whether or not you want to avoid discussion about a new ethics of consciousness is irrelevant. It’s coming. Much of our survival depends on it.

—

Derek Beres is working on his new book, Whole Motion: Training Your Brain and Body For Optimal Health (Carrel/Skyhorse, Spring 2017). He is based in Los Angeles. Stay in touch @derekberes.