To our brains, people of other races really do look alike

- We are better at distinguishing between the faces of people of our own race than those of other races. This is the “other-race effect.”

- Social and cognitive scientists have debated whether this effect is due to racial bias or perceptual expertise.

- An experiment involving brain stimulation shows that a lack of perceptual expertise is the likely explanation.

Every face is different, and we can distinguish between remarkably similar faces within racial groups we are familiar with. However, this ability is impaired when distinguishing between faces from other races. For example, to the naïve Western Caucasian, all East Asian people might look alike, while to the naïve East Asian, all Western Caucasian people might look alike. It’s a well-documented neuropsychological phenomenon known as the “other-race effect.”

Why does it occur? Many social scientists suggest it is a consequence of racial bias: Individuals, particularly those with more prejudiced racial attitudes, are not motivated to differentiate between members of other races. Consequently, the person would simply perceive the face as belonging to an other-race group instead of working to identify the nuances that indicate it is the face of an individual. But is racism or bias really the best explanation?

Other cognitive scientists argue that a lack of perceptual expertise causes the other-race effect. Individuals with little visual experience with other-race individuals have not learned to recognize subtle facial nuances. In other words, it’s not a lack of motivation; it’s a lack of knowledge.

The face inversion effect

Why would someone need experience with other-race individuals to distinguish between their faces? After all, regardless of race, people generally have the same facial features: two eyes, a nose, a mouth, etc. We even have shared facial expressions.

Face recognition experts say that individuality lies in the configuration of these features. How far apart are your eyes? What’s the slope of your nose in relation to the angle of your eyebrows? Are your cheekbones more or less dominant than your chin? Previous research has shown that we tend to trust faces with configurations similar to our own. Also, according to one explanation of the other-race effect, an individual unfamiliar with another race processes the individual facial features of that race but lacks the expertise to appreciate the relationships between those features. The most robust evidence in support of this is the face-inversion effect.

Over 300 studies have shown that we have difficulty recognizing upside-down faces, even faces we’re familiar with. This is the face inversion effect (FIE), and its most widespread explanation is that, when presented upright, we process faces based on how the facial features are configured. However, our ability to do this is severely impaired when a face is flipped upside-down. This effect occurs regardless of race, but it is much smaller for other-race faces compared to same-race faces. Many cognitive scientists believe that this is evidence that we process other-race faces configurally, just as we would an upside-down face.

Brain shock

Ciro Civile and Ian McLaren, a pair of psychologists at the University of Exeter, wanted to examine the nature of the other-race effect directly by blocking the brain from applying its perceptual expertise. Suppose the other-race effect is indeed due to expertise in own-race face configurations. In that case, the effect should disappear if the researchers blocked the brain region responsible for learning new information based on previously learned pattern configurations. Furthermore, blocking this region — the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) — should have little or no effect on the recognition of other-race faces considering that there is less expertise to be lost for these faces. To do this, Civile and McLaren used transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). This non-invasive, painless treatment uses direct electrical currents to stimulate specific parts of the brain.

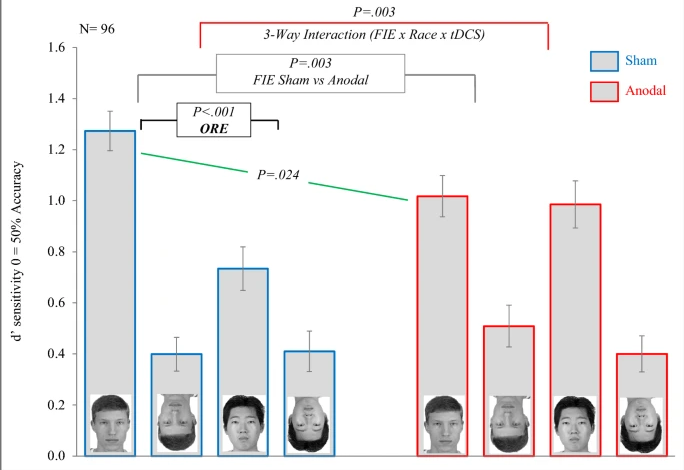

The psychologists recruited 96 self-declared Western Caucasian subjects (with an average age of 21, and 62 of whom were women). All subjects were University of Exeter students who had lived in Exeter (a town in the southwest of England with a population that is about 90% Western Caucasian) for at least two years. Before that, they all lived in countries where Western Caucasian faces are primarily predominant (like the U.S. or other European nations). The subjects either were assigned to the treatment (tDCS) or the sham (unstimulated) group.

All same-race faces look alike

First, Civile and McLaren showed each subject photos of 40 upright (20 male and 20 female) and 40 inverted (20 male and 20 female) Western Caucasian and East Asian faces. The subject’s only job was to remember as many faces as possible. Next, the researchers showed the same faces again plus 80 new faces (half upright and half inverted). All 160 faces were presented one at a time in random order, and the subject had to respond whether they thought the faces were new or seen previously.

As expected, the unstimulated control group showed a face inversion effect for own-race faces that was almost three times larger than the one for other-race faces. This was because the subjects were almost twice as likely to recognize own-race faces in the upright orientation compared to other-race faces. The subjects who received tDCS, however, showed no difference in face inversion effect for own- versus other-race faces, supporting the hypothesis that people use previously learned pattern configurations to distinguish between individual faces. Essentially, the tDCS made the same-race faces look alike.

“Establishing that the other-race effect, as indexed by the face inversion effect, is due to expertise rather than racial prejudice will help future researchers to refine what cognitive measures should and should not be used to investigate important social issues,” said McLaren. “Our tDCS procedure developed here at Exeter can now be used to test all those situations where the debate regarding a specific phenomenon involves perceptual expertise.”