As early as the 1970s, studies have demonstrated that repeating a claim increases that claim’s truth value. In other words, the more often you hear a particular statement, the more likely you are to accept that statement as being true. In the scientific literature, this process is referred to as truth-by-repetition or TBR for short.

Researchers still don’t fully understand why TBR occurs, but one possibility is that it has something to do with processing fluency. Neurologically, our brains have an easier time processing things we have already heard before compared to things we have not, thereby mistaking familiarity for legitimacy.

For a long time, researchers assumed that TBR only works on statements whose truth value is ambiguous or unknown to the test subjects. “Otherwise,” as one article published in 2009 puts it, “the statements’ truthfulness will be judged on the basis of their knowledge and not on the basis of fluency.”

Like an oft-repeated claim, this assumption was accepted almost without question and readily incorporated into multinomial processing tree (MPT) modeling, a popular method for assessing the psychological processes that underpin human behavior. However, recent studies suggest that the truth value of a statement need not be ambiguous for TBR to work its magic.

One study from 2015, for instance, found that TBR applied to statements that contradicted the participants’ prior knowledge, like, “The Atlantic Ocean is the largest ocean on Earth.” Another research paper, published in 2018, discovered a relationship between TBR and fake-news headlines shared on social media.

These studies suggest that TBR could work on any kind of claim, regardless of whether its truth value is ambiguous or not. However, they are not conclusive. While claims like, “The Atlantic Ocean is the largest ocean on Earth,” are false, many people lack the knowledge needed to recognize them as such. Similarly, the implausibility of fake news does not become obvious until you have been exposed to different sources, something fake news victims actively avoid.

If researchers really wanted to figure out if sheer repetition increases the validity of claims with unambiguous truth values, they are better off using statements that nearly everybody recognizes as false, such as, “The Earth is a perfect square.” This, incidentally, is exactly what a team of psychologists from Belgium’s UCLouvain set out to do in a recent study.

The authors of the study, which will appear in the June issue of the academic journal Cognition, asked participants to judge repeated statements as more true or less false compared to unrepeated ones, and they found that people “started giving credence to statements as highly implausible as ‘The Earth is a perfect square’ or ‘Benjamin Franklin lived 150 years’ after repeating them for just five times.”

The power of repeating lies

The study concludes that “even a limited number of repetitions can alter the perceived truth of highly implausible statements.” This conclusion is not exactly revolutionary, nor is it watertight. In 2020, researchers conducted a similar experiment that led them to completely opposite results — namely, that repeating claims at high frequency decreases their perceived truth value.

That does not necessarily discredit the study conducted at UCLouvain. If anything, it reaffirms the notion that repetition is strongly linked to perceived truth value and that, depending on quality and context, the correlation can either be positive or negative, resulting in either truth-by-repetition or fakeness-by-repetition.

Propaganda involves repetition

Nowhere is the double-edged power of repetition demonstrated more clearly than in the history of propaganda. As a form of communication, propaganda as we know it today did not emerge until the start of the First World War. During this time, governments around the world figured out how to produce and distribute large, colored lithographs on a national, even global scale.

“In all countries involved in the war,” Doran Cart tells Big Think, “these lithographs or posters were produced in large numbers. Not only as propaganda, but also to mobilize people for the war effort.” Cart is a historian and senior curator at the National World War I Museum. Located in Kansas City, Missouri, the museum has one of the largest collections of propaganda posters in the world.

Before the war, political information was shared primarily through newspapers. Posters were preferable for several reasons. First and foremost, they were a primarily visual medium. Ideas and arguments were presented not only through text but also through images and symbols that could be understood immediately, regardless of whether the viewer knew how to read.

They were also a technological novelty. In a time when even movies were still being shown in black-and-white, propaganda posters were among the earliest colored images. Color gave them a lifelike quality that, in Cart’s words, helped “grab the passerby’s attention.” Posters were not glanced at, but studied at length, especially in small towns.

Last but not least, they were ubiquitous. Articles had to be stuffed inside the crowded pages of newspapers, but posters could be hung anywhere and everywhere: on walls, fences, billboards, lamp posts, and sandwich boards (wooden boards that people wore around their torso as they paraded down the street to display certain messages).

According to Cart, repetition played a key role in the distribution and effectiveness of propaganda posters. “You couldn’t get any place in the United States without running into them,” he says. Often, multiple copies of the same poster design were placed in the same location, similar to how you sometimes see multiple television screens display the same channel.

This kind of repetition served several purposes. For one, it ensured the messaging displayed on the posters was all but impossible to ignore. More importantly, though, it allowed governments to turn their various poster designs into a codified language. As the pervasiveness of this language in everyday life increased, so too did its processing fluency.

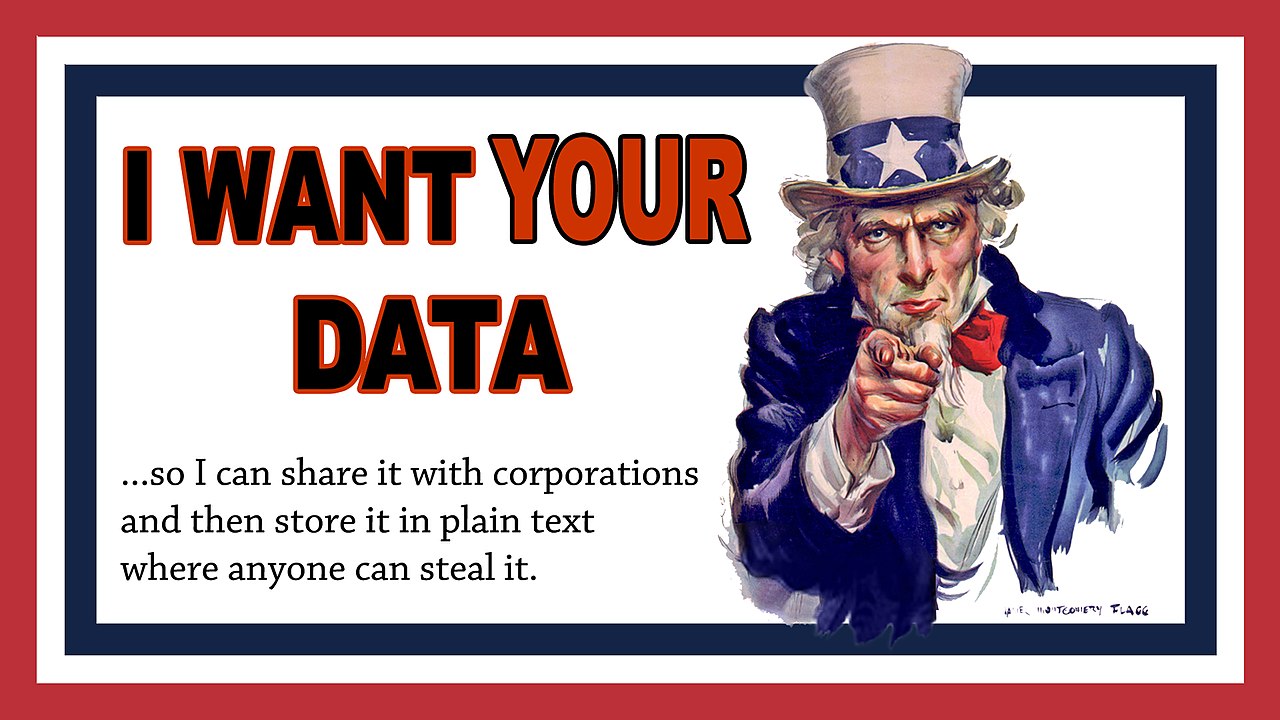

In other words, the more familiar people were with a particular poster design, the less effort they required to process its meaning. Cart cites the famous “I Want You” poster as an example. Over time, the poster’s original meaning became associated with and represented by the iconic pose of Uncle Sam pointing directly at the viewer with a stern look on his face.

The “I Want You” poster became so iconic that it turned into a meme — that is, a widely known visual template that can be modified for different situations, yet remains easily understandable. It has not only been used by other countries as part of their mobilization efforts, but also to make political statements, like this one concerning Putin’s war in Ukraine.

Finally, propagandists have used repetition to both falsify and verify specific claims. During the Second World War, the Allies used posters as well as animated cartoons to cast doubt on information that was being shared by Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. Topics ranged from the size of their armies to the technical prowess of their weaponry.

American propaganda in World War I, concludes Cart, repeated its principal themes “like a kind of drumbeat.” The heroic image of the patriotic soldier risking his life for the country, as well as the ideal of the American home that needs to be defended from foreign enemies, are two examples of images introduced during this period that, through their sheer repetition, are generally regarded as unquestionable today.