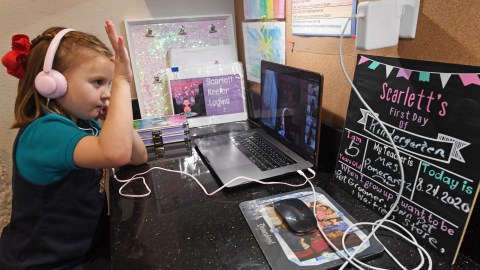

Remote education is decreasing anxiety, increasing wellbeing for some students

Credit: Ethan Miller/Getty Images

- With coronavirus resurging in Europe and the United States, parents are worried about their children’s well-being and mental health.

- A report from the U.K.’s NIHR extends some hope; it found that students’ mental health is improving while remote learning.

- Parents will continue play an important role in supporting their children’s mental health.

As coronavirus cases resurge, European states have begun the second round of shutdowns and business closures. Across the Atlantic, 10 million people have been infected in the U.S., and rates of new infections continue to climb while the country waits to see how leadership will respond after a contentious election.

This leaves children and teens in with a bitter lot. During this period of life, they’re developing the knowledge and social skills that will serve them in their future pursuits, yet the pandemic has either stripped them of these critical connections or diluted the potency of such interactions through the hazy blue light of a computer monitor. Add to that the mental stressors of massive upheaval and unknowns, and it’s little wonder that parents, teachers, and community leaders are worried about young people.

But according to a survey performed by the National Institute for Health Research, the kids are doing all right. By some metrics, they’ve been doing better in our era of lockdowns and remote education.

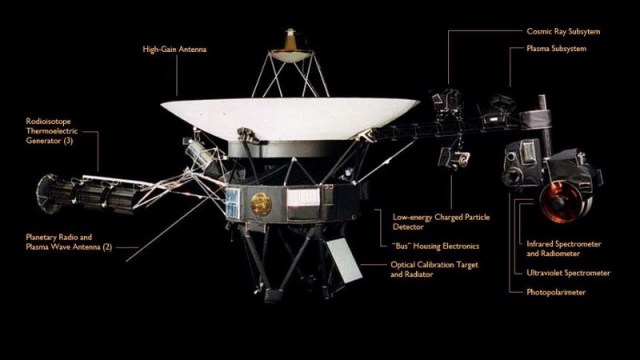

U.K. showed a reduction of at-risk depression scores during the pandemic lockdown.Credit: NIHR

“The Young People’s Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic” report surveyed more than 1,000 Year 9 students (ages 13 to 14) in the United Kingdom. This ongoing study aims to chronicle the relationship between social media use and adolescents’ mental health. Because the study participants took the initial survey in October 2019, researchers were able to compare the students’ pre-pandemic baseline with their responses several months into lockdown. (Schools closed in the U.K. in mid-March; follow-up surveys were completed in April and May.)

The researchers discovered that mental health among the U.K.’s adolescents has, surprisingly, improved during these trying times. Although 90 percent of students agreed that COVID-19 is a serious issue, their responses indicated an overall decrease in their risk of anxiety, an increase in their well-being, and no major changes to their risk of depression.

The most improvement was seen in students struggling with poor mental health. Students with low well-being scores in October last year showed a 10-point gain on the Warwick-Edinburgh Wellbeing Scale; meanwhile, students with previously average-to-high well-being scores showed no significant change. Students at risk of anxiety and depression also showed small advances in their Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores. The only group showing a heightened risk of depression were girls, and the difference was slight.

What caused this mental uplift among U.K. youth? While the study does not attempt to answer that question, the researchers speculate it may be “due to the removal of stressors within the school environment, such as pressure of academic work, and challenging peer relationships including bullying.”

Another possibility is that this cohort’s pandemic stressors are more externally focused. They cited their top three concerns as worrying their friends or family would catch the disease, worrying over friends and family’s mental health, and worrying about missed school. Far fewer were anxious about catching the disease or the lockdown’s effect on their friendships, job prospects, or the larger economy.

The researchers asked about students’ connectedness with school, peers, and family, too. Students reported an increased connection with school and no change in their relationships with friends and family. Those with the lowest connectedness scores in the baseline survey again saw the greatest gains in well-being scores and anxiety reduction scores. And, of course, social media use has supersized.

The researchers write, “As schools fully re-open, it is important to consider ways to prevent a rise in anxiety back to pre-pandemic levels.”

There are limitations to the study, however, and we should be careful not to extrapolate these data too broadly. Younger children, the researchers note, do not have the same level of access to social media as their older peers nor are their vital social interactions as easily digitized. The playground cannot be translated into text and emojis with the same fidelity as the lunchroom clump. As a consequence, younger children may be experiencing a very different pandemic. That may also be true for young people undergoing transitional periods in their life.

Nor did the researchers see the same improvements in vulnerable student populations, such as LGBTQ teens and those with disabilities. These students reported higher anxiety and depression scores pre-pandemic and did not see the same improvements in the pandemic follow-up survey. This outcome suggested to the researchers that these students continued to experience stressors even when not attending school physically.

Finally, there’s no indication that teens in other countries will face the pandemic the same. In countries with weaker social safety nets, such as the U.S., students may be far more worried about the virus’s impact on their health and future prospects.

Hyper-innovation: COVID-19 can forever change the way we teach kids | Richard Culatta | Big Thinkwww.youtube.com

The National Institute for Health Research’s report showing young teens are more resilient than adults may give them credit, but it bases its findings on student responses from mere months into the pandemic. Unfortunately, we won’t know how remote education and prolonged shutdowns will affect them until they’ve been experienced. This reality means parents still play a critical role in supporting their children’s mental health.

Parents looking for strategies can find resources at The Centers for Disease Control, the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center, and other health institute websites. In general, experts recommend keeping adolescents on a routine that supports learning, exercise, and social connection. This schedule should lead them to accomplish goals, partake in their interests, and engage with social activities—even if those social engagements must be taken online.

Yes, screen time will increase but parents need to remember that not all screen time is created equal. There’s a difference between screen time dedicated to, say, playing board games with friends versus mindlessly wandering the social media wastes. Parents will still need to incorporate boundaries and converse regularly with teens on what information they are receiving about coronavirus and the pandemic.

As Nilu Rahman, Johns Hopkins Children’s Center senior child life specialist, said: “Teens have great access to the internet and some of what they’re reading about the coronavirus and the pandemic might be scaring them, even if they don’t say so.” Rahman added that “parents should make sure kids are not going down rabbit holes and getting confused or frightened by false information.”

Parents should also remain alert for changes in behavior, as these may signal boosted stress or other underlying mental health concerns. Rahman recommends parents look out for extreme eating habits, changes in sleep patterns, signs of self-harm, increased isolation, or their children not enjoying their favorite hobbies and past times.

“Parents know their children best,” she says, “so if something seems off about their teen, they should trust their instinct and find out what’s going on, especially if the child has a history of depression or anxiety.”