Your brain keeps getting faster until you hit your 30s

- Brain development continues well into the third decade of life.

- The protracted brain maturation process involves widespread changes in white matter distribution and neuronal transmission speeds.

- Conduction delays in neuronal transmission decrease throughout childhood and adolescence and continue well into adulthood.

One of the more significant neuroscientific discoveries of the 21st century is that human brain development continues well into the third decade of life. Although the brain begins to approach its full adult size at ten years of age, it undergoes a protracted maturation period that continues throughout adolescence and well into early adulthood.

This has major implications for society. It helps to explain why teenagers take big risks; it suggests that education can be reformed to optimize learning; it is beginning to influence how minors are viewed by the legal system; and, in several cases, it has even persuaded the U.S. Supreme Court to issue landmark opinions about the criminal culpability of juveniles.

Much of what we now know about brain development has been gleaned from neuroimaging studies of how the structure and function of the organ change over time, and from postmortem examination of its microscopic structure at different ages.

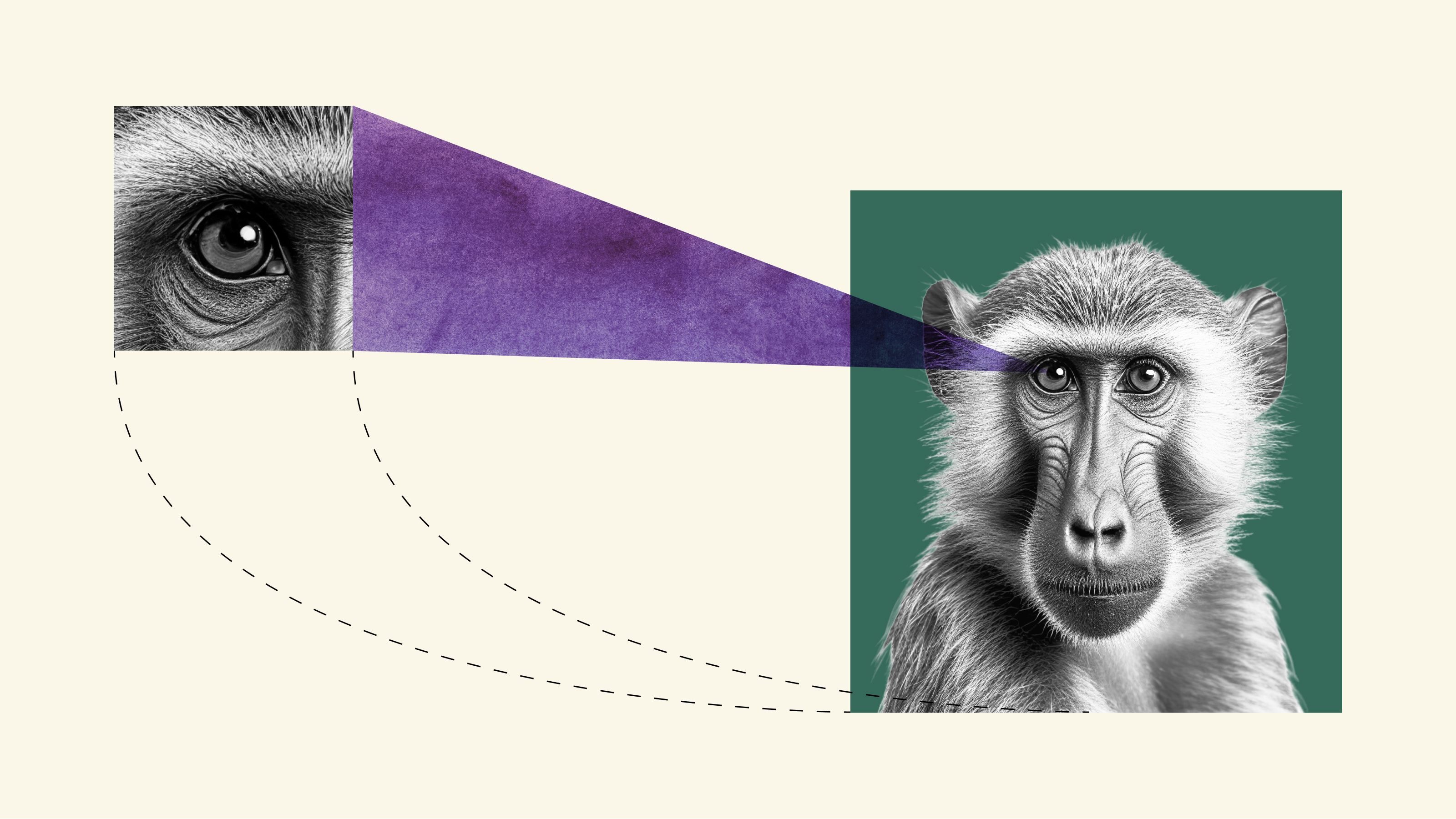

Transmission speed

Dorien van Blooijs of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester and her colleagues adopted a different approach: They electrically stimulated the cerebral cortex in 74 patients undergoing surgery for drug-resistant epilepsy, so that they could record the timing of responses in adjacent areas of the brain.

Measuring the short delay between stimulus and response enabled them to calculate the speed of neuronal transmission. And because their patients were between 4 and 64 years old, they could see how transmission speed matured during early life and how it changed throughout adulthood.

The researchers performed these measurements within and between multiple brain regions in the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes. Their results, published in Nature Neuroscience, revealed variability between the patients, but overall, the delays in conduction decreased throughout childhood and adolescence, continuing, in most of the patients they examined, well into adulthood. One patient who was 35 years old had the highest transmission speed.

Long-range fibers connecting distant brain regions showed the greatest increases in transmission speed, doubling from 1.5 to 3 meters per second in childhood to 3 to 6 meters per second in adulthood. The transmission speed of short-range connections between neighboring brain regions showed smaller increases, reaching speeds of up to 2 meters per second in adulthood.

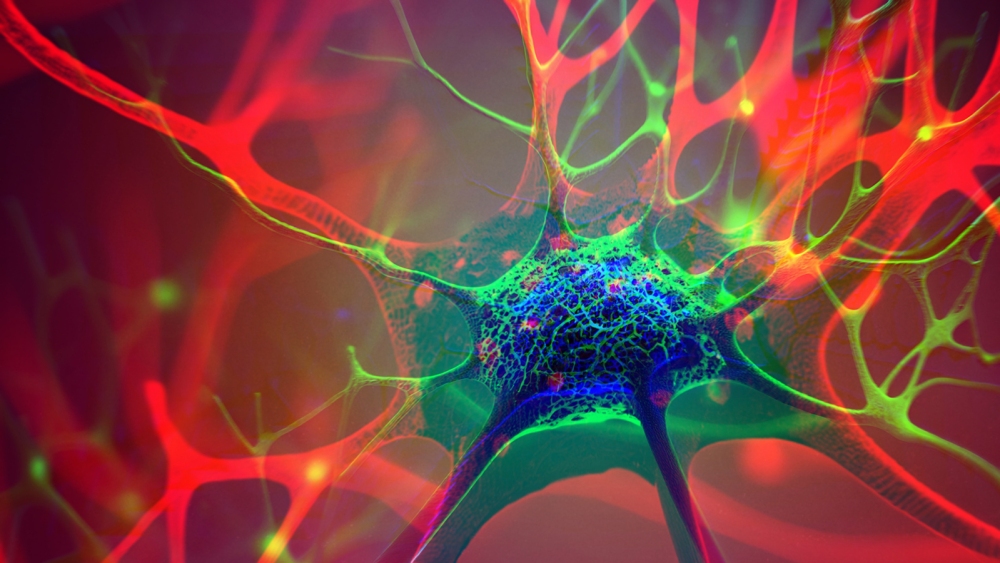

Brain wiring

Transmission speed is determined by white matter, which consists of myelin, the fatty insulating tissue that, in the brain, is produced by non-neuronal cells called oligodendrocytes, and wraps itself around nerve fibers in a process called myelination. By analogy, myelinated neurons are akin to copper wires (neurons) surrounded by a plastic sheath (myelin). Myelinated neurons transmit signals faster than neurons without it.

Earlier postmortem studies suggested that myelination begins just before birth and continues into late adolescence, while brain imaging shows that the process plateaus at around 30 years of age. But previous studies of transmission speed provide highly variable results, with some showing that conduction delays decrease until 20 years of age before increasing, and others showing that they continue to decrease until 40 years of age.

These inconsistencies may be due to the fact that each of these studies used different methods to examine different regions of the brain. In recent years, it also has become clear that myelin distribution is not static, but changes in response to everyday experiences such as learning. This white matter plasticity may be another confounding factor in these studies, and a source of variability in this latest study.

Even so, the new results are generally in keeping with the idea that brain maturation continues well into the third decade of life, and the finding that transmission speeds continue increasing throughout adolescence and early adulthood could help to explain why psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia tend to develop during this stage of life.