Faulty memory is a feature, not a bug

In 1942, the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges published a short story called “Funes the Memorious.” The unnamed narrator recounts a story from his memory, which centers on a Uruguayan man named Ireneo Funes. The narrator learns Funes has fallen off his horse, hitting his head and leaving him housebound. Not long after, Funes contacts the narrator, asking to borrow some of his books in Latin, which is the narrator’s specialty. He gives Funes a selection of his most difficult Latin texts, ones that he has trouble making sense of himself.

A few days later, when the narrator goes to collect his books, he finds that Funes has memorized, in just a matter of days, long and complicated passages in Latin, despite no prior knowledge of the language. Funes tells the narrator that, ever since the accident, his memory has changed. He no longer can forget. As Funes describes it, his experience is now of one “intolerable richness and sharpness.” Whereas the rest of us look out and see a tree here, a group of people there, Funes sees the pixel-level information, frame by frame. Because he retains the full clarity of these scenes in memory, his memories have indistinguishable precision when compared to his present reality.

Funes details the consequences of his now infallible memory. Sleep eludes him and he finds basic aspects of language perplexing. It is difficult for him to comprehend that the word dog“embraces so many unlike individuals of diverse size and form.” And, “his own face in the mirror, his own hands, surprised him every time he saw them.” Even though Funes had learned Latin and several other languages with little effort, the narrator suspects Funes “was not very capable of thought. To think is to forget differences, generalize, make abstractions. In the teeming world of Funes, there were only details, almost immediate in their presence.” In the morning, the narrator leaves for Buenos Aires. He never sees Funes again.

Borges, who died in 1986, had a remarkable memory himself. The Argentine writer memorized many texts from a young age, knowing that he would eventually lose his eyesight and his ability to read due to a congenital condition. Writer and neuroscientist Rodrigo Quian Quiroga learned these details about Borges in 2009, when he visited Borges’ widow María Kodama in Buenos Aires. Quiroga, who recounts the visit for a piece in Nature, also toured Borges’ private library, which revealed the author’s lifelong interest in psychology and neurology. In “Funes the Memorious,” Borges anticipated what modern neuroscience has evidenced. We make our way through the world precisely because we forget, generalize, and make abstractions. The act of memory is an act of imagination.

In 1985, the Estonian-Canadian psychologist Endel Tulving, with the help of his American student Daniel Schacter, reported a case study of an amnesiac patient named N.N., who had a severe memory impairment.1 What interested Tulving about the patient was that while some aspects of the man’s memory were impaired, other aspects seemed to work just like anyone else’s.

N.N. was perfectly able to memorize a series of random digits, what cognitive psychologists call semantic memory—the ability to recall facts, dates, names, numbers, and other abstract information. The problem was N.N.’s episodic memory. He was unable to bring to mind personal experiences from his life. Tulving wrote that “N.N.’s knowledge of his own past seems to have the same impersonal experiential quality as his knowledge of the rest of the world.” It was about as intimate as his knowledge of, say, Thomas Jefferson’s life—a collection of abstract facts. He couldn’t recall the specifics of any events he’d experienced himself, not a single birthday party, vacation, or social encounter.

Memory provides the building blocks for mental time travel.

The thrust of Tulving’s report centered around this dissociation between semantic and episodic memory, how it was possible to have one without the other. But there was another observation Tulving reported, though he was unsure what to make of it. Not only was N.N. incapable of remembering past personal events, he couldn’t imagine future ones either. In one conversation with N.N., Tulving began with the question, “What will you be doing tomorrow?” After a pause, N.N. replied: “I don’t know.”

“Do you remember the question?” asked Tulving.

“About what I’ll be doing tomorrow?” said N.N.

“Yes,” said Tulving. “How would you describe your state of mind when you try to think about it?”

“Blank, I guess,” N.N. responded.

When pressed by Tulving, N.N. described his attempts to imagine his own future as “like being asleep.” His effort to imagine a personal future felt as empty as his effort to remember his personal past: “It’s like swimming in the middle of a lake. There’s nothing there to hold you up or do anything with.”

The case of N.N. suggested to Tulving that there was potentially a neural connection between memory and imagination—that our ability to think retrospectively about the past was in a fundamental way connected to our ability to think prospectively about the future. Poet T.S. Eliot’s famous line, “Time present and time past / Are both perhaps present in time future,” had entered the neurological age.

Schacter, Tulving’s student, remained intrigued by the implied connection between memory and imagination. Later, as an established professor, he began a line of inquiry with Donna Rose Addis, a New Zealand neuroscientist, and his post-doc at the time, that explored the connection directly.

Misremembering and forgetting allow for the cognitive flexibility required by imagination.

In their initial study, Addis, Schacter, and their colleagues presented participants with a series of cue words (mostly simple nouns like “automobile” or “tree”).2 These were designed to elicit images that were both familiar to most people and that could be concretely imagined. For each cue word, participants were asked to bring a related event to mind. Half of the time, they were asked to recall an event that had already happened. In the other half, they were asked to imagine an event that could conceivably happen in the future. They were also given a specific timeframe for the events: one week, one year, or five to 20 years in the past or future.

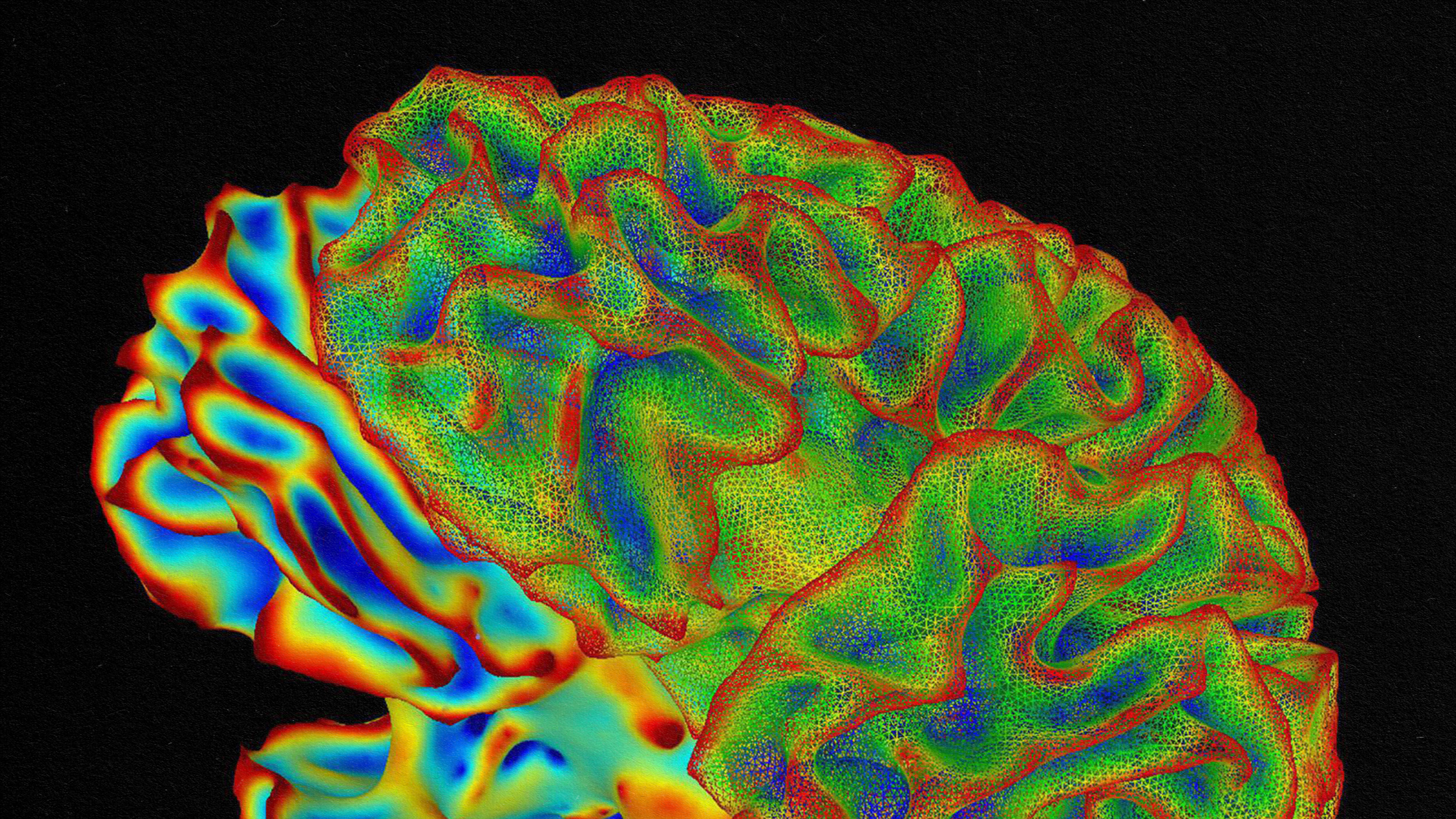

Addis and her colleagues wanted to know what would happen in their subjects’ brains when they were engaged in acts of memory and imagination, and so they scanned the subjects’ brains while they brought these images to mind. What the researchers found was that, as the case study of N.N. suggested, the same areas appeared to be recruited for both memory and imagination.

“We found that it was the same brain network” Addis told me, “also known as the default mode network, which is activated very strongly, very robustly, both when people were remembering the past and imagining the future.”

In a paper published the same year, Addis and her colleagues argued that this finding, together with other emerging evidence of connections between memory and imagination, gave crucial insight into one of the adaptive functions of memory: It allows us to plan for the future.3 It provides the building blocks for mental time travel.

Taking this idea a step further, Addis and others suggested that memory supports a “simulation” system in the brain. Memory allows us to imagine not just the future, but to take alternative perspectives on the present. We use the building blocks of memory to imagine the thoughts or experience of another and to see our present surroundings or situation in novel ways. This memory-based simulation allows us to produce creative solutions to myriad problems.

Over the past decade, our understanding of memory’s role in creativity has only grown. Researchers have linked false memories and forgetting to creative performance. And earlier this year, Schachter and colleagues published a paper that suggests that memory plays an extensive part in every stage of the creative process.4 “Creative ideation is supported by the controlled retrieval” of memories, they wrote. Proust would certainly agree.

Misremembering and forgetting allow for the cognitive flexibility required by imagination. If, like Funes, we remembered every single bit of our experience in a rote, fixed way, we would not be able to pull bits from here and there to build a vision of something totally new. “The interesting thing is that when you’re remembering, you don’t remember every single thing that you experienced,” Addis said. “You have to fill in the gaps. And there’s often a lot of gaps. That’s just how memory works.”

These gaps, evidently, are very important. But how does the human brain know where to leave them and when it’s worth recording in painstaking detail? How does it know what to forget? The fact is, as far as your brain is concerned, almost nothing is worth keeping. The first thing we do with most of the information we take in about the world is to forget it.

Cognitive psychologists typically distinguish between three stores of memory, each of which catalogs information on a different timescale. Iconic memory is the shortest. When you look out onto a scene and then quickly shut your eyes, there is the briefest moment in which that scene is still retained in your mind before it evaporates into the darkness behind your eyelids.

How does the human brain know what to forget?

In order to have an experience of a visual scene, your brain needs to store the information somewhere. This is technically a form of memory, and it allows you to do things like look across the street and count the number of windows on the adjacent skyscraper. The middle-length store of memory is called working memory. This is what you can keep in mind via deliberate concentration—for example, if I read you a phone number. It is a kind of memory purgatory: It briefly holds onto the information that is too important to discard immediately but that may not be worth keeping forever. The longest store is long-term memory. These are the things you learn today which you can still recall tomorrow, or the next day, or 10 years from now. If you repeated the phone number enough times to recall it later—psychologists call this “rehearsal”—it would be stored in long-term memory. How long it stays there ranges from the next few minutes or hours to the rest of your life.

The reason that we forget between the stages of iconic, working, and long-term memory is clear. It is the same reason we remember a chess board by its alternating squares and not by the individual pixels of black and white paint. Not all information is useful. Some things get logged in our memories attached to strong emotion, such as surprise or awe, love or fear—a powerful signal to the brain that the event, scene, fact, or idea will in some way be essential to our survival. Other information is rehearsed naturally, by means of experience. Certain events and details are repeated over time—the daily bus ride to school when you are a kid, for instance, or the way your dog greets you when you return home from a trip—and so they are stored in memory again and again, reinforcing their permanence.

Recent research suggests that for frequently repeated patterns of experience—a waiter who must remember dozens of complex orders from diners each night, for example—this process involves complex memory structures known as “templates,” which allow information that is statistically regular in our environments to slot more easily into place for long-term retrieval.

Beyond emotional cues and rehearsal, there is yet another way a piece of information may get logged in long-term memory: It is associated with conceptual information stored there. We understand it.

One of the first lines of psychological research to show this was a series of classic studies run in the early 1970s by Herbert Simon and William Chase.5 Simon and Chase showed arrangements of pieces on a chessboard to two groups of participants. The first group consisted of experienced chess players, the second of people who hadn’t played before. When researchers showed them random arrangements of pieces, which were incoherent and would never occur naturally in a game, both groups did just about the same. But when the arrangements were reflective of situations from an actual game, the experienced chess players were able to recall the arrangements of the pieces with almost perfect clarity. The novices didn’t do any better than they did for the random arrangements. Exactly how to interpret this finding has been a matter of debate among cognitive psychologists ever since. But a recent review that summarizes the decades of subsequent research suggests that, at least for experts, memory relies not just on recognition of familiar patterns, but high-level conceptual understanding.6

A classic study by cognitive scientist John R. Anderson suggests that even the average person may store memories in conceptual buckets.7 Anderson asked his participants to memorize lists of conceptually related words (such as sugar, candy, sour, good, taste) and then recall them later on. The trick was that when participants were given the recall test, Anderson also put “lure” words among the ones they had seen. These lure words weren’t part of the original list, but some of them were conceptually related to the initial list of words (e.g., “sweet”).

He found that participants were more likely to falsely recall conceptually related lure words than unrelated ones. The test subjects remembered not just the words, but the general category they implied. This effect has since been replicated, including using pictures instead of words. The point is that the brain doesn’t just store inert facts which can simply be recalled or forgotten. It makes guesses about the larger conceptual story, generating assumptions and filling in the gaps as it goes—using imagination to create the whole, to build a world that we can step into.

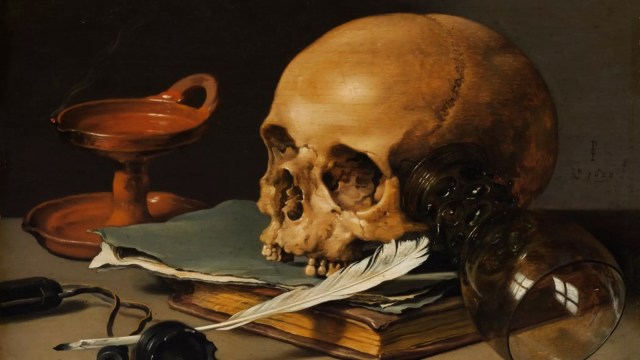

“We are our memory,” Borges wrote, “that chimerical museum of shifting shapes, that pile of broken mirrors.” And it’s true. Everything we see, do, and imagine is built upon past experience, stored in broken bits that must be reassembled again and again, reflecting our past onto the present and far into the future.

References

1. Tulving, E. Memory and consciousness. Canadian Psychology 26, 1-12 (1985).

2. Addis, D.R., Wong, A.T., & Schacter, D.L. Remembering the past and imagining the future: Common and distinct neural substrates during event constructions and elaboration. Neuropsychologia 45, 1363-1377 (2007).

3. Schacter, D.L., Addis, D.R., & Buckner, R.L. Remembering the past to imagine the future: The prospective brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 8, 657-661 (2007).

4. Benedek, M., Beaty, R.E., Schacter, D.L., & Kenett, Y.N. The role of memory in creative ideation. Nature Reviews Psychology 2, 246-257 (2023).

5. Chase, W.G. & Simon, H.A. The mind’s eye in chess. In Chase, W.G. (Ed.) Visual Information Processing Academic Press, Cambridge, MA (1973).

6. Lane, D.M. & Chang, Y.-H.A. Chess knowledge predicts chess memory even after controlling for chess experience: Evidence for the role of high-level processes. Memory & Cognition 46, 337-348 (2018).

7. Deese, J. On the prediction of occurrence of particular verbal instructions in immediate recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology 58, 17-22 (1959).

This article originally appeared on Nautilus, a science and culture magazine for curious readers. Sign up for the Nautilus newsletter.