New study seeks to explain the Mandela Effect – the bizarre phenomenon of shared false memories

Imagine the Monopoly Man.

Is he wearing a monocle or not?

If you pictured the character from the popular board game wearing one, you’d be wrong. In fact, he has never worn one.

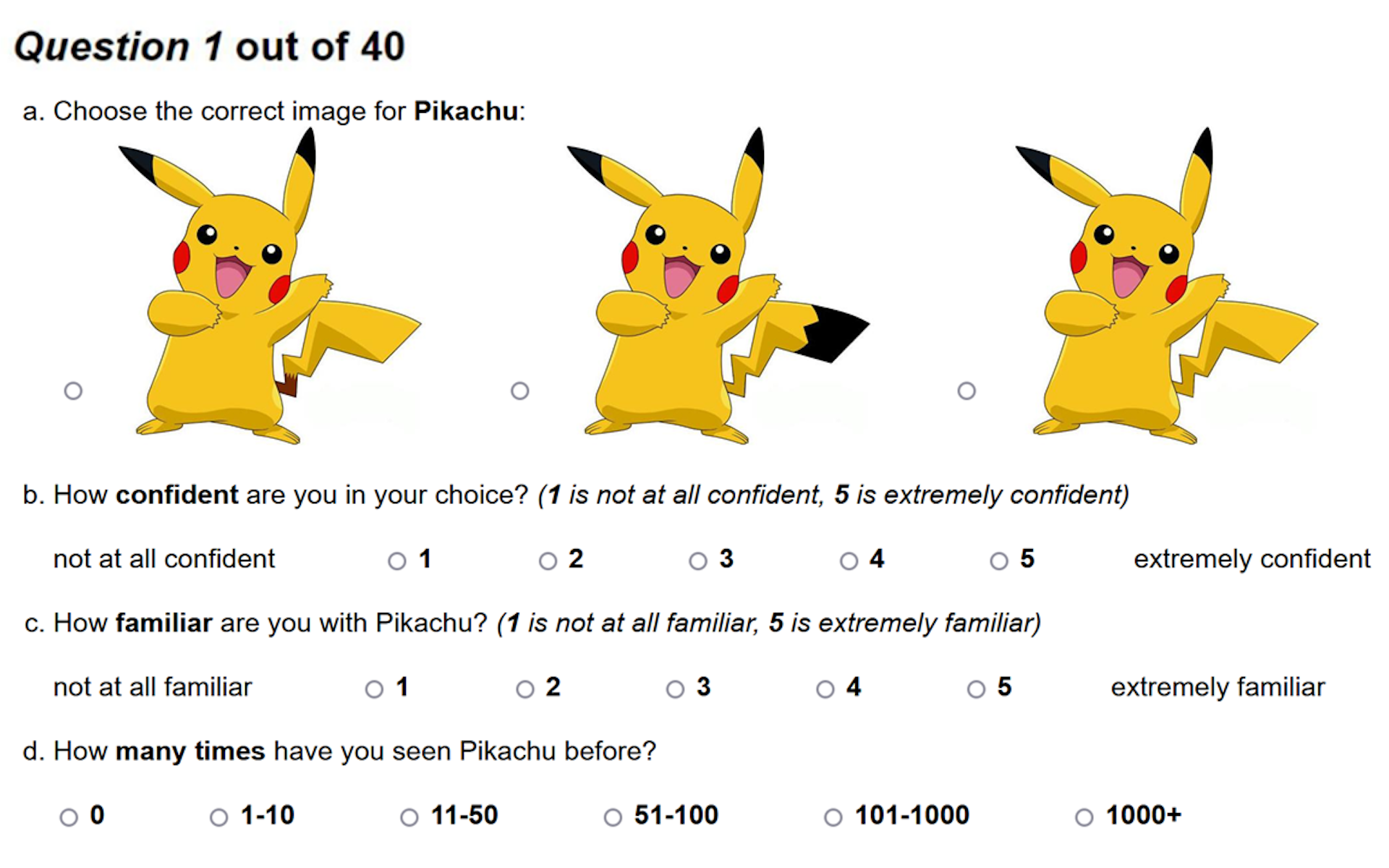

If you’re surprised by this, you’re not alone. Many people possess the same false memory of this character. This phenomenon takes place for other characters, logos and quotes, too. For example, Pikachu from Pokémon is often thought to have a black tip on his tail, which he doesn’t have. And many people are convinced that the Fruit of the Loom logo includes a cornucopia. It doesn’t.

We call this phenomenon of shared false memories for certain cultural icons the “visual Mandela Effect.”

People tend to be puzzled when they learn that they share the same false memories with other people. That’s partly because they assume that what they remember and forget ought to be subjective and based on their own personal experiences.

However, research we have conducted shows that people tend to remember and forget the same images as one another, regardless of the diversity of their individual experiences. Recently, we have shown these similarities in our memories even extend to our false memories.

What is the Mandela Effect?

The term “Mandela Effect” was coined by Fiona Broome, a self-described paranormal researcher, to describe her false memory of former South African president Nelson Mandela dying in prison in the 1980s. She realized that many other people also shared this same false memory and wrote an article about her experience on her website. The concept of shared false memories spread to other forums and websites, including Reddit.

Since then, examples of the Mandela Effect have been widely shared on the internet. These include names like “the Berenstain Bears,” a children’s book series that is falsely remembered as spelled “-ein” instead of “-ain,” and characters like Star Wars’ C-3PO, who is falsely remembered with two gold legs instead of one gold and one silver leg.

The Mandela Effect became fodder for conspiracists – the false memories so strong and so specific that some people see them as evidence of an alternate dimension.

Because of that, scientific research has only studied the Mandela Effect as an example of how conspiracy theories spread on the internet. There has been very little research looking into the Mandela Effect as a memory phenomenon.

But understanding why these icons trigger such specific false memories might give us more insight into how false memories form. The visual Mandela Effect, which affects icons specifically, was a perfect way to study this.

A robust false memory phenomenon

To see whether the visual Mandela Effect really exists, we ran an experiment in which we presented people with three versions of the same icon. One was correct and two were manipulated, and we asked them to select the correct one. There were 40 sets of icons, and they included C-3PO from the Star Wars franchise, the Fruit of the Loom logo and the Monopoly Man from the board game.

In the results, which have been accepted for publication in the journal Psychological Sciences, we found that people fared very poorly on seven of them, only choosing the correct one around or less than 33% of the time. For these seven images, people consistently identified the same incorrect version, not just randomly choosing one of the two incorrect versions. In addition, participants reported being very confident in their choices and having high familiarity with these icons despite being wrong.

Put together, it’s clear evidence of the phenomenon that people on the internet have talked about for years: The visual Mandela Effect is a real and consistent memory error.

We found that this false memory effect was incredibly strong, across multiple different ways of testing memory. Even when people saw the correct version of the icon, they still chose the incorrect version just a few minutes later.

And when asked to freely draw the icons from their memory, people also included the same incorrect features.

No universal cause

What causes this shared false memory for specific icons?

We found that visual features like color and brightness could not explain the effect. We also tracked participants’ mouse movements as they viewed the images on a computer screen to see if they simply didn’t scan over a particular part, such as Pikachu’s tail. But even when people directly viewed the correct part of the image, they still chose the false version immediately afterward. We also found that for most icons, it was unlikely people had seen the false version beforehand and were just remembering that version, rather than the correct version.

It may be that there is no one universal cause. Different images may elicit the visual Mandela Effect for different reasons. Some could be related to prior expectations for an image, some might be related to prior visual experience with an image and others could have to do with something entirely different than the images themselves. For example, we found that, for the most part, people only see C-3PO’s upper body depicted in media. The falsely remembered gold leg might be a result of them using prior knowledge – bodies are usually only one color – to fill in this gap.

But the fact that we can demonstrate consistencies in false memories for certain icons suggests that part of what drives false memories is dependent on our environment – and independent of our subjective experiences with the world.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.