10 incredible books from Jordan Peterson’s ‘Great Books’ list

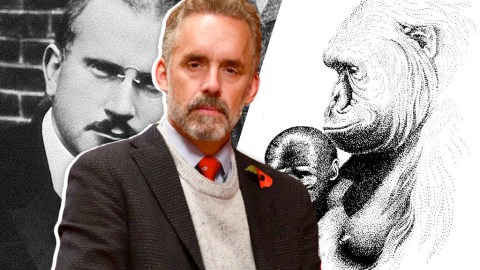

Jordan Peterson with Carl Jung and the cover art of Jaak Panksepp's 'Affective Neuroscience' (Image: Chris Williamson/Getty Images/Big Think)

- Peterson’s Great Books list features classics by Orwell, Jung, Huxley, and Dostoevsky.

- Categories include literature, neuroscience, religion, and systems analysis.

- Having recently left Patreon for “freedom of speech” reasons, Peterson is taking direct donations through Paypal (and Bitcoin).

We like to know what informed thinkers we respect, to better understand what shaped their worldview. On his website, Jordan Peterson offers his Great Books list, granting insight into the turning of his own mind. I’ve discovered a few that I’ll pick up from the numerous titles that he offers. The following ten also resonated with me.

Island — Aldous Huxley

Everyone loves dystopia. There’s a reason we all have to read Inferno in high school yet most people don’t even realize Paradiso exists—it was a terrible ending to the trilogy. Island was Aldous Huxley’s utopian counterpart to Brave New World, yet unlike Dante, he concluded this series (and his life; it was his last novel) quite well. This is a more reflective, psychedelic-loving Huxley sharing his profound connection to Buddhist philosophy in the guise of the disbelieving writer, Will Farnaby. The myna birds screaming “Attention!” throughout the book serve as an important reminder to everyone walking around with their head glued to a screen today.

The Grapes of Wrath — John Steinbeck

This is simply one of the greatest novels of 20th-century America. I think of it often, reading about Amazon caravans traveling around the country in RVs seeking the next factory to try to work at. Not much has changed in the nearly 70 years since Steinbeck published this masterpiece. Too many Americans are still clawing at the imagined dream. This book is the poet and patriot in his finest moment.

The Denial of Death — Ernest Becker

This book was my introduction to philosophy and psychology, given to me by my brother-in-law’s brother while I was in high school. It opened my eyes to the reality of fear and death, and the reality that most of our fears are rooted in the existential threat of biology. It’s also Becker wrestling with his own questioning and validation of Freudian psychology. I also recommend the posthumous follow-up, Escape From Evil.

Answer to Job — Carl Jung

Jung saw this book as describing the unmentioned fourth face of God: evil. It’s hard to read the biblical book any other way (though many have tried). Jung doesn’t mince mythologies, however. Unlike the “ultimate perfection” of God as espoused by many religious, Jung sees his treatment of one of his most faithful as the deity’s own development—a sharp rebuke to anyone believing in an ultimate good, but also a valuable lesson that we’re all works in progress.

Affective Neuroscience — Jaak Panksepp

You have to love any man that tickled rats for a living. The Estonian neuroscientist did much more during his illustrious career, but discovering that rats laugh is certainly a highlight. It’s part of the mammalian PLAY system, one of seven primary affective systems included in our neurological hardware. The recently deceased Panksepp knew what separated humans from the other animals, but perhaps more importantly, he devoted his career to what united us all.

Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy — Mircea Eliade

Everyone in America (and beyond) who calls themselves a “shaman” because they’re certified in yoga and have tried ayahuasca needs an actual education, and that starts with this book. Eliade was one of the greatest religious thinkers of the 20th century, also penning one of the best scholarly books on yoga. Just as Joseph Campbell discovered links between archaic religions, Eliade sought out common occurrences in shamanic practices across the planet, writing them down in this exquisite work.

The World’s Religions — Huston Smith

Originally titled The Religions of Man, Smith’s publisher was early in the #metoo movement, realizing it didn’t reflect the religious inclinations of an entire gender. Not the case for Smith, however, who discovered mysticism after a Methodist upbringing. He was a lovely man and beautiful writer, appealing to our highest angels in his lifelong pursuit of comparative religion. While he produced many important books over his 97 years, his debut remains a class in the field.

Animal Farm — George Orwell

Whenever I see an animal tackle a social cause in a Pixar movie, I credit George Orwell. Of course, we’ve been anthropomorphizing other species for millennia, projecting our fears and strengths onto them. Orwell worked as a police officer in Burma, a political journalist in Paris, and a teacher in England before settling into his novelist career. He put a history of experiential knowledge into Animal Farm, an overt critique of Stalinist Russia. Too bad he’s not around today to serialize the current state of affairs on his old beat.

The Origins and History of Consciousness — Erich Neumann

Two Jungians seriously evolved their teacher’s knowledge. James Hillman dove deep into archetypal psychology, while psychologist Erich Neumann wrote a number of important works, including this opus. In it he explores the mythical ouroboros as the catalyst for unconscious urges stretching into conscious awareness. There is plenty that doesn’t hold up in this work—he believed that homosexuality was the result of underdevelopment and that even in women, consciousness has a masculine bent. But his exploration of creation and hero mythology makes this a fascinating read.

The Emotional Brain — Joseph LeDoux

Few neuroscientists have taken anxiety as seriously as LeDoux. While his last book, Anxious, is the book on the topic of anxiety and the human nervous system, he laid the groundwork in this 1996 classic. Even though we don’t face the types of threats we endured for hundreds of thousands of years, our brain’s threat detection system is what relates us to the rest of the animal kingdom. We like to think we’ve scaled to the top of that pyramid, but from a neurological perspective, we’re still running through the proverbial forest seeking shelter at every turn.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook.