Feeling Bad About Feeling Bad? Embrace Negative Emotions Instead, Study Says

Has anyone ever told you to “smile!” or “cheer up!” while you were trudging through a bad day? That’s actually awful advice, according to new research that suggests habitually accepting negative emotion rather than criticizing or smothering it is significantly better for your long-term psychological health.

The study, which was funded by the National Institute of Aging and published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, analyzed the relationship between the acceptance of negative emotion and psychological health in 1,300 adults.

“We found that people who habitually accept their negative emotions experience fewer negative emotions, which adds up to better psychological health,” said study senior author Iris Mauss, an associate professor of psychology at UC Berkeley, to Berkeley News.

Feelings of disappointment, sadness or resentment appeared to inflict more damage upon people who avoided them, or criticized themselves for experiencing such emotions.

“It turns out that how we approach our own negative emotional reactions is really important for our overall well-being,” said study lead author Brett Ford, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Toronto, to Berkeley News. “People who accept these emotions without judging or trying to change them are able to cope with their stress more successfully.”

(“Manic Depression” source)

In total, the researchers conducted three studies, all of which factored in age, gender, socioeconomic status and other demographic variables.

The first study was a survey in which 1,000 participants rated how strongly they agreed with statements like “I tell myself I shouldn’t be feeling the way that I’m feeling.” Participants who were hard on themselves, which is to say they felt bad about feeling bad, reported lower levels of psychological well-being.

In the second study, 150 participants came into the lab and gave a three-minute mock job interview to a panel of judges and a video camera, and they were only given a couple minutes to prepare. After the interview, participants were asked to evaluate their emotions. The results showed again that the people who tend to avoid negative feelings reported higher levels of emotional distress.

Finally, the researchers asked more than 200 people to write about their most distressing experiences over a two-week period. Six months later, those who felt bad about feeling bad showed more mood disorders than those who embraced their darker feelings.

—

To learn more about handling negative emotion, I asked study lead author Brett Ford about habitual acceptance and society’s fixation on being happy. (Edited and condensed for clarity.)

Is there research that indicates habitual acceptance is associated with any particular personality trait, or is it more likely that people learn it through parents or culture?

This is a great question, and it’s one that we don’t yet have a thorough empirical understanding of — there’s much more work to be done regarding who are the people who end up frequently using emotional acceptance in their daily lives.

We do know a bit about these people though and two particular lines of work come to mind. First, teaching emotional acceptance is an element in several beneficial psychotherapies (e.g., Mindfulness based cognitive therapy, Acceptance and commitment therapy, Dialectical behavioural therapy). Second, we’ve found in our own research that emotional acceptance is correlated with age (Shallcross et al., 2013): in a sample of 21-73 year olds, age predicted greater habitual acceptance. Given that this wasn’t a longitudinal study tracking people as they age, we can’t say for sure that individuals gained more acceptance as they aged, but there are several compelling reasons to expect that habitual acceptance increases as people get older (e.g., aging promotes wisdom, aging co-occurs with uncontrollable stressors during which can promote acceptance, etc).

How can people go about cultivating habitual acceptance?

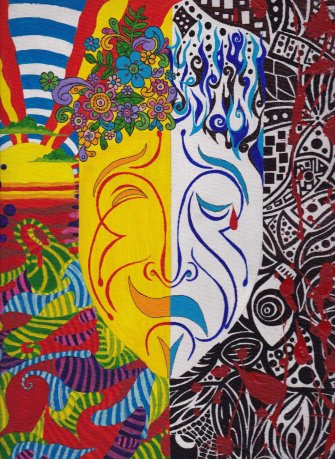

Acceptance might look a little like the following:

When times are tough and you’re feeling angry, worried, sad, and so forth — try to simply let your feelings happen. Allow yourself to experience your feelings, without judging those feelings, and without trying to control or change them. Let your feelings run their course. For example, you could tell yourself that there is no right or wrong way to respond, that these feelings are a natural response, or that your feelings are like clouds passing by that you don’t need to control.

I’m reminded of this scene from “Curb Your Enthusiasm.” Do you think this research can tell us anything about how we should interact with people who are clearly experiencing negative emotions? Should we not say “smile!” or echo sentiments like “cheer up!”?

Another great question, and another one that deserves (but hasn’t yet received) much empirical research! In general, the research on how we manage and regulate other people’s emotions is relatively sparse. Developmental researchers have actually been studying this for quite some time given their interest in how parents help regulate their children’s emotions, but the rest of psychology just now seems to be catching up.

There is a lot more to learn about which strategies are most helpful when used for or on behalf of other people (vs. ourselves). There’s good reason to expect that emotional acceptance might be particularly helpful to employ when someone else is upset, compared to strategies that hinge upon the individual ‘feeling better.’ When people are comfortable feeling unpleasant emotions, it can be quite invalidating to have other people (even close friends) try to get them to ‘cheer up’, ‘ look on the bright side’ and so forth. I’m reminded of an interesting study from Denise Marigold and colleagues, where individuals with lower self-esteem (who are more comfortable feeling negative than their high self-esteem counterparts) don’t want their friends to help them “look on the bright side”. They are still quite amenable to support that comes in the form of acceptance and validation, though.

It seems like the West is a bit obsessed with the idea of being happy, and that this fixation might lead to the stigmatization of negative emotion – do you think that’s an overreach or oversimplification?

That’s not an overreach — we believe the two ideas are indeed linked. The opposite of accepting one’s emotions is judging one’s emotions; And while there are many factors that can contribute to the judgment of one’s emotions, we think that desperately valuing and wanting to feel happiness can lead to greater judgment of one’s lack of happiness (including one’s negative emotions).

…When you have people on the street asking you to smile and friends telling you to ‘cheer up’, it begins to make sense why ours is a culture that tends to value happiness and devalue negative emotions.