World’s oldest forest found in New York state

- The world’s oldest forest fossils were located in an abandoned quarry near Cairo, New York.

- Research of site specimens suggests that the forebearers to modern plants evolved much earlier than expected.

- The findings help scientists better understand how trees advanced life’s evolutionary trajectory to land during a critical period.

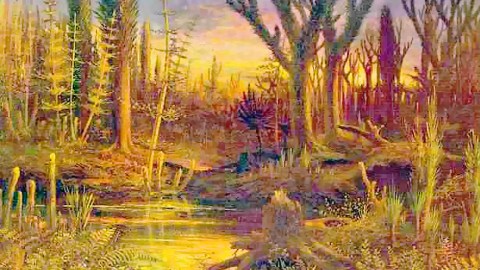

As card-carrying members of the universe’s exclusive Terrestrial Existence Club, we don’t give the Devonian period near enough credit. Beginning 416 million years ago, this period of the Paleozoic era blazed the trail toward manufacturing a surface habitable to life.

New plant species evolved that could survive on dry land. The fresh-faced forests drew carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, beginning a process that would drastically refashion the planet’s climate. Insects and arachnids proliferated, while early tetrapods flirted with land’s safety in the newly-formed wetlands – allowing many animal ancestors to escape the mass extinction event soon to devastate the Earth’s oceans.

Flash forward to 2019, researchers in an abandoned quarry near Cairo, New York, have discovered a 385-million-year-old Devonian forest, the world’s oldest to date. Their findings, published this month in Current Biology, are helping scientists better understand the enigmatic origins of terrestrial life.

Researchers explore an Archaeopteris root system at the Cairo fossil forest site.

And into the forest science goes

Today, this ancient arboretum exists in the form of fossilized root systems. Slices of prehistoric botany spread horizontally across the ground, with the quarry acting like a giant, stone microscope slide. Some roots measure 15 centimeters in diameter and form 11-meter-wide radial patterns.

“The Cairo site is very special,” paleobotanist Christopher Berry, a team member at Cardiff University, told Science. “You are walking through the roots of ancient trees. Standing on the quarry surface, we can reconstruct the living forest around us in our imagination.”

After analyzing the root systems, the researchers suggest the presence of three different groups of extinct plants: Eospermatopteris, Archaeopteris, and a currently obscure specimen.

Eospermatopteris was a palm tree-like plant well-represented in the Devonian fossil record. These trees had lofty trunks that crowned into “branchlets”—effectively frond-like groupings of stalks that were photosynthetic yet predated broad, flat leaves. They reproduced by spores and sported a rudimentary root system with a limited range.

Considered an intermediate between land plants and the ancestors to modern ferns and horsetails, Eospermatopteris is plentiful at another fossil forest located nearby, at a quarry near Gilboa, New York. The Gilboa site was the previous record holder for the oldest fossil forest.

The fossilized remains of the world’s oldest fossil forest in the abandoned sandstone quarry.

A glimpse of the oldest forests takes root

But the other two root systems are unique to the Cairo site. Archaeopteris shares several characteristics with modern seed plants. These characteristics, many assembled in tandem for the first time in the fossil record, include an upright habit, laminate leaves, endogenous root production, and more contemporary vascular systems.

Archaeopteris’ appearance at the Cairo site means the genus took root roughly 20 million years earlier than previous estimates. The discovery helps clarify the enigmatic evolution of trees and forests during the Devonian period, as well as the indelible ripple effect they had on Earth’s ecology, geochemical cycles, and atmospheric makeup.

As for the third specimen, it is represented by a single obscure root system. The researchers postulate it may belong to the class Lycopsida, a.k.a. “scale trees.” These trees dominated the Late Carboniferous coal swamps, and the oldest fossils date back to the Late Devonian. However, like Archaeopteris, its presence at the Cairo site may push current estimates deeper into prehistory.

“Our findings are perhaps suggestive that these plants were already in the forest, but perhaps in a different environment, earlier than generally believed. Yet we only have a footprint, and we await additional fossil evidence for confirmation,” William Stein, the study’s first author and an emeritus professor of biological science at Binghamton University, said in a statement.

He added, “It seems to me, worldwide, many of these kinds of environments are preserved in fossil soils. And I’d like to know what happened historically, not just in the Catskills, but everywhere.”

Climate change, then and now

When and how trees began evolving modern root and vascular systems, as well as their upright habit, remain a mystery. But Archaeopteris’ elongated rooting systems appear identical to trees that would become numerous in the Carboniferous period’s vast swamp forests.

As trees evolved these root systems, they began pulling carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and turning it into carbonate ions in groundwater. These ions then flowed into the oceans where they were locked away in limestone, preventing them from re-entering the atmosphere. This development added a new wrinkle to Earth’s substance turnovers.

Originally, carbon dioxide content in the atmosphere constituted more than 95 percent. Soon after the introduction of vascular plants and forests, these levels began dropping to modern levels. By the Carboniferous, oxygen levels reached an all-time high of 35 percent. Today, they remain at a respectable, and livable, 21 percent. Thanks to vascular plants.

Vascular plants have modified other geological cycles on a planet-wide scale, too. These include deposition and erosion, the physical characteristics of soil, and the cycle of freshwater and various elements.

As Stein noted in the same statement:

The effects were of first order magnitude, in terms of changes in ecosystems, what happens on the Earth’s surface and oceans, in global atmosphere, CO₂ concentration in the atmosphere, and global climate. So many dramatic changes occurred at that time as a result of those original forests that basically, the world has never been the same since.

Today, Devonian plants and their Carboniferous progeny are again altering the Earth’s climate, but in a way that is making the world less hospitable to life.

After being buried for millions of years, the remains of these giant plants transformed under the heat and pressure to create the large reserves of coal that drove the Industrial Revolution. In fact, the name “Carboniferous” references to the rich coal deposits found in this geologic layer and literally means “coal-bearing.”

As we continue to burn these ancient fossil fuels, we release the carbon dioxide they trapped back into the atmosphere, where they heat up our planet by way of an enhanced “greenhouse effect.” Ironically, it seems powering our planet with these plants’ remains is undoing the hard work the world’s first forests endeavored.