New research reveals why some octopuses punch fish

Credit: pr2is / Adobe Stock

- Octopuses are part of multispecific collaborative hunting groups with bottom-feeding fish.

- New research shows octopuses defending their territory by punching fish.

- The team believes this research helps reveal underlying game structures in the deep sea.

The psychologist William James noted that consciousness did not arrive in the universe fully formed. Phenomena like perception and memory are in no way limited to our own form of consciousness, though humans often pretend we’re evolution’s crowning achievement. In many reckonings, all timelines end with Homo sapiens. Because of this errant belief, we’ve both exalted our own kind while treating other species as lesser forms on the road to our greatness.

Good science is not so egotistical. We should study other species, as evolutionary threads can be picked from their development to help us weave the story of ourselves. Such endeavors require imagination. Thomas Nagel succinctly posed the hard problem of consciousness in a 1974 essay in which he wondered aloud what it’s like to be a bat, setting off decades of debate over the nature of consciousness.

We can, and arguably should, also wonder what it’s like to an octopus—if we can.

Australian science philosopher Peter Godfrey-Smith argues that intelligence is not a straight line to humans, but rather evolved separately in cephalopods (such as octopuses and cuttlefish) and vertebrates, like us. Humans might ponder the hard problem of consciousness, a question that splits fans of emergent phenomena with dualists, but the bottom dweller known as the octopus has no time for such a debate. Godfrey Smith writes,

“In an octopus, the nervous system as a whole is a more relevant object than the brain: it’s not clear where the brain itself begins and ends, and the nervous system runs all through the body. The octopus is suffused with nervousness; the body is not a separate thing that is controlled by the brain or nervous system.”

An octopus body, Godfrey-Smith argues, in some sense transcends the brain-body divide—neither embodied cognition nor disembodied spirit. Rather, it’s “all possibility.” Nagel, according to Godfrey-Smith, flubbed the question: the octopus is like something, just nothing like a human, therefore making it difficult to even define.

Alas, we can’t help but anthropomorphize. Octopuses might maintain a vastly different intelligence, yet like us, they’ve had to figure out how to survive in challenging environments. As a new study, published in The Scientific Naturalist, shows, they seem to do that, in part, by punching fish.

Our evolutionary success is due in large part to group fitness: we work together well. On occasion, we collaborate with other species to our mutual benefit, as with hunting dogs. The authors of this study point out that ocean life is filled with multispecific collaborative hunting groups, such as moray eels and groupers. Octopuses get in on this action as well.

“Involving active recruitment and referential gestures, the nature of this relationship is mutually beneficial (byproduct mutualism); that is, both can increase their hunting success rate from the presence of the other species, which likely played an important role in the emergence of complex interactions between groupers and eels.”

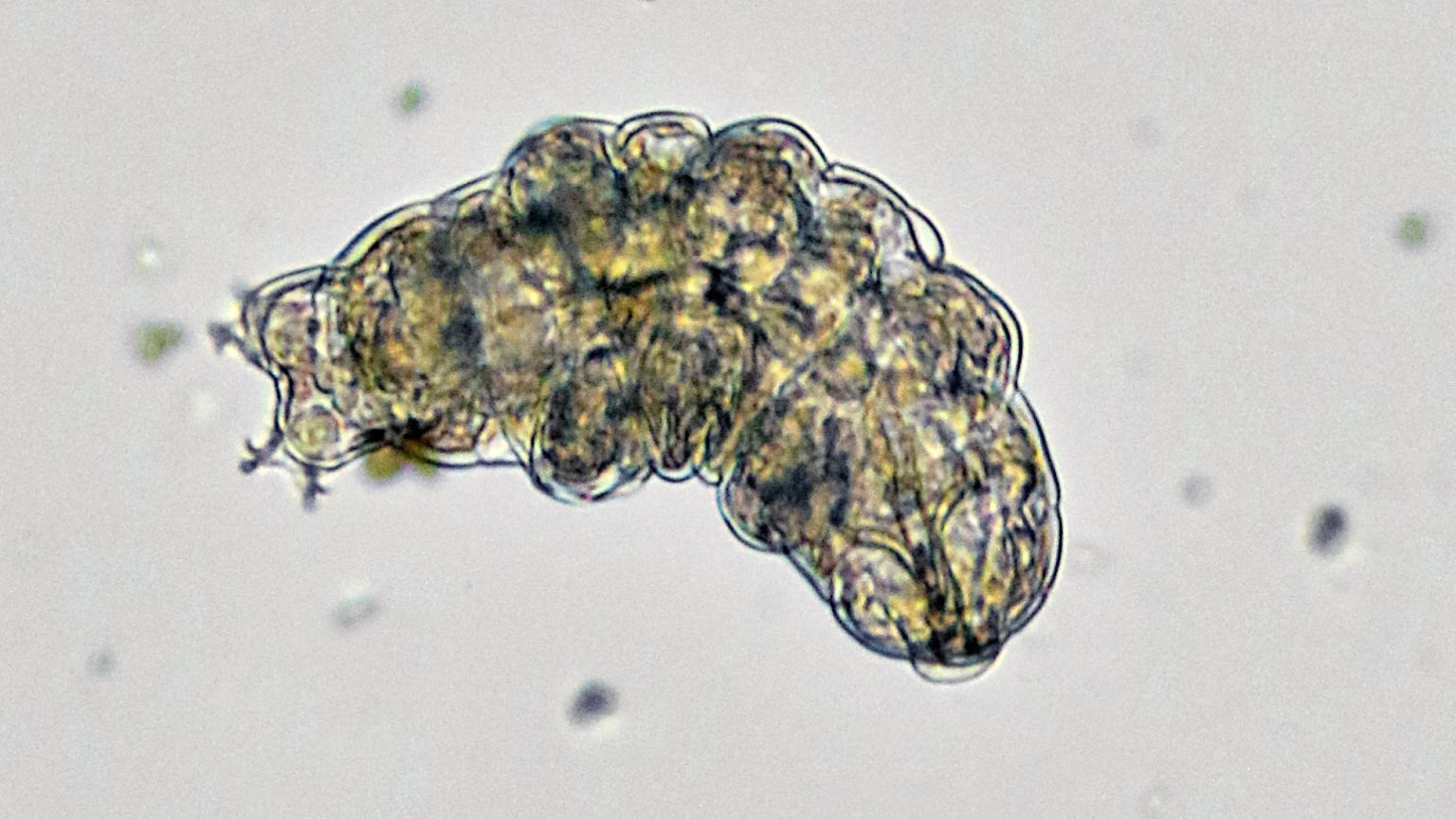

Image sequence depicting the behavioral action of Octopus cyanea punching (white arrows) a yellow‐saddle goatfish (Parupeneus cyclostomus) partner during interspecific multicollaborative hunting.

Coral reef fishes have made bonds with other ocean life, such as octopuses, who chase prey within rocks and coral crevices while bottom-feeders scour the seafloor. Octopuses are known to tail groupers on hunting expeditions. As with any complex social network, however, life is not all mutual benefit. Tensions rise.

Recording instances in Israel in 2018 and Egypt in 2019, the team observed octopuses punching collaborating fish when things got heated. The goal appears to be moving the fish to a less advantageous location or simply telling them to scram.

“Thus, from the octopus’s perspective, punching serves as a partner control mechanism, the nature of which is dependent on the ecological context of the interaction, and on how the octopus benefits from inflicting costs on fish partners.”

As Godfrey-Smith writes, octopus arms are partly self and partly non-self—each arm is, in a sense, autonomous. To extend a metaphor, breathing is autonomic yet we can also control it. So too each octopus arm travels on its own but also coordinates with the rest of the body. The central brain, he continues, is like a conductor, with each arm being an improvisational jazz player, paying attention to the structure of the song while meandering off when needed.

We will never know what it’s like to be an octopus. Nature has branched intelligence in distinctly different directions. Perhaps we share common ground on the hunt for survival. The team believes that research on punching octopuses helps reveal underlying game structures in the deep sea. And maybe, in some form of interspecies solidarity, we can appreciate their method of defending territory.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook. His most recent book is “Hero’s Dose: The Case For Psychedelics in Ritual and Therapy.”