Photo Ark: See dazzling images of the Earth’s animals

(Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark)

- The Photo Ark by photographer Joel Sartore and National Geographic brings the viewer face to face with our planet’s fellow travelers.

- It’s predicted that half of earth’s species may be lost before 2100.

- This collection of images is beautiful and profound.

You’ve probably seen some of Joel Sartore’s remarkable photos of animals. He’s an award-winning regular contributor to National Geographic magazine — in fact, he’s the 2018 Rolex National Geographic Explorer of the Year. Whether it’s a shot of a salmon seemingly launched from a waterfall straight into a hungry Alaskan bear’s mouth, or a spotlit Ugandan lion waking in a tree at dusk from a nap, his photos are as striking as they are iconic.

Speaking to Big Think by phone, Sartore says of the National Geographic Photo Ark, “We’re really trying to give a voice to all these voiceless animals, maybe the only time they get to tell their story before the go away.” At 8,485 images so far, he’s roughly halfway through the world’s estimated 12,000 species.

It’s believed that, due mostly to habitat loss and pollution, about half of the animals currently alive will be gone by the end of this century.

From October 13, 2018 through January 13, 2019, the Annenberg Photo Space in Los Angeles is hosting a stunning Photo Ark exhibition. The Photo Ark can also be experienced on Sartore’s site online. You can purchase a number of Photo Ark books, and you can contribute to this massive, time-sensitive effort.

Sartore and National Geographic have graciously consented to our sharing a few of our favorite Photo Ark images.

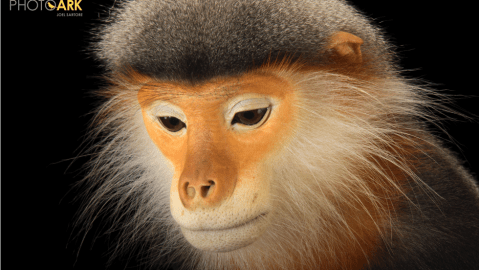

A male, grey shanked douc langur, Pygathrix cinerea, at the Endangered Primate Rescue Center.

(Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark)

Grey shanked douc langur

What’s so breathtaking about Sartore’s photos are the way in which they seem to reveal the innermost thoughts of his subjects. This heartbreaking image of a langur depicts a being lost in his thoughts, and it’s difficult to tear one’s eyes away.

After getting to meet so many animals up close, Sartore says this is no illusion: “They’re as smart as we are, most of them. They’ve got feelings and emotions just like we do.”

A Fiji Island banded iguana, Brachylophus fasciatus, at the Los Angeles Zoo.

(Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark)

Banded Iguana

Here’s an expression that seems to say, “Don’t think I don’t see you there.” It’s a great example of the importance Sartore places on capturing an animal’s eyes, presuming, of course, that they have some. It’s key to taking such absorbing, arresting portraits.

“It’s really a matter of getting some eye contact. That’s what we, as primates, respond to,” says the photographer. And so, we “to try to look these animals in the eye to realize that there’s a lot of intelligence there, and that these animals are worth saving.” He takes a lot of pictures to get what he wants: “We use flash so it freezes motion — all they have to do is look at me for a second , just long enough for me to get a focus.”

The last known Rabbs’ fringe limbed tree frog, Ecnomiohyla rabborum, at the Atlanta Botanical Garden.

(Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark)

Rabbs’ fringe limbed tree frog

While we love to look at impressive or adorable creatures, Sartore tells us, “The Photo Ark’s made for the animals that aren’t necessarily cute. I mean, everybody knows what gorillas and tigers look like, but these little freshwater fish that live in streams the are going to dry up when the glaciers melt completely, or some animal that lives in leaf litter, or in the soil, or high up in the trees, from slugs to snails to salamanders, toads, sparrows, this is what the Photo Ark’s actually built for, to present these animals in a way we can actually see them. They may live in muddy water — well, in these pictures we can see them very clearly for a change. I would say 90% of what people will see in this show has not been photographed well, or even alive.

One animal we’d never get to see is the Rabbs’ fringe limbed tree frog, above. This one is the very last one there is.

Joel Sartore

(Graham S. Jones, Columbus Zoo and Aquarium)

Here’s a look at Joel Sartore, the photographer behind the Photo Ark

About 12 years ago, sidelined by a family medical crisis — since resolved — Sartore set out on a mission, in partnership with National Geographic, to create a photographic “ark” of all the world’s living species before they’re gone. It’s believed that, due mostly to habitat loss and pollution, about half of the animals currently alive will be gone by the end of this century.

Three critically endangered, yearling Burmese star tortoises, Geochelone platynota, at the Turtle Conservancy.

(Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark)

Burmese star tortoises

The animals in the Photo Ark are photographed in zoos around the world using in Sartore’s portable studio. Its shape changes to accommodate each animal — sometimes it’s a tent, sometimes a platform, sometimes a specially decked-out room. The shooting background is always either white or black to avoid distractions and to present all animals on equal footing, so to speak.

We asked Sartore how he felt about zoos in general — they’re often criticized as being more exploitive than helpful to animals. “Now remember, I work at really good zoos,” says Sartore. “Nobody likes a bad zoo. We work at zoos where there’s abundant attention and care. And these are the places that are the real arks — they’re not simple menageries any more. For many of the species I photograph, they only exist in these zoos now — they’re extinct in the wild. So if the zoos gave up on them, they would be extinct.” He adds, “If we don’t have zoos we’ll lose a really profound connection to nature, and that’s the first step to not caring about nature at all.”

Sartore adds, “So it’s critically important for people to remember that zoos are breeding critically endangered species for a time when we can revegetate the planet — hopefully that day will come — and also they do a tremendous job in terms of education.”

An endangered Malayan tiger, Panthera tigris jacksoni, at Omaha Henry Doorly Zoo.

(Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark)

Malayan Tiger

“As these species go away, so will humanity,” says Sartore. “We’re all tied together.” He sees the photographs as “a little bit of a trick to get people into the tent of conservation, if you will.”

Looking at so many emotionally compelling portraits, the enormity of what we stand to lose becomes more inescapable with each image. This is intentional, Sartore says: “Each animal can stand on its own, but when you think about collectively we could lose half of all species to extinction by the turn of the next century, that comes with great peril to our own kind.”

In explaining how humans and animals are tied together, he notes, “If we cut down all the trees, the rain forest, we disrupt the rain cycle in the world to the point where we won’t be able to grow crops. If we use so many chemicals and eliminate so much habitat that we get rid of the pollinating insects, then we don’t get fruits and vegetables any more.”

Jonathan Baillie, current chief scientist of the National Geographic Society, is an author of a proposal to protect 30% of the earth from human impact by 2030 and half by 2050 to save ourselves from that cataclysmic loss of habitats on which we ourselves depend.

A Coquerel’s sifaka, Propithecus coquereli, at the Houston Zoo.

(Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark)

Coquerel’s sifaka

We asked Sartore how seriously he takes the idea of recreating extinct species via remaining samples of DNA. The answer: Not very. “That’s not a good backup plan because, you know, if we weren’t willing to save them when they were here in the first place, are we really going to spend a million dollars to bring back some bird or some mammal? Not unless it’s going to make somebody a lot of money. We really do need to restore habitats right now. I mean right now.”

An endangered baby Bornean orangutan, Pongo pygmaeus, named Aurora, with her adoptive mother, Cheyenne, a Bornean/Sumatran cross, Pongo pygmaeus x abelii, at the Houston Zoo.

(Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark)

Bornean Orangutans

“As these species go away, so will humanity. We’re all tied together,” says Sartore, and that’s the point of the Photo Ark. The images are meant to strike a chord in us, and “If we can just start to think about this, if the public can just start to think about this thing, which they’re not now, then eventually we’ll get better rules on the books and we will, hopefully, change the trajectory of where we’re headed. It’s a generational thing, and it’s not going to be solved overnight,” he continues. “There are complicated problems, but the first step is to kind of meet our neighbors and learn that there’s a big world out there with a lot of great stuff that’s worth saving.”