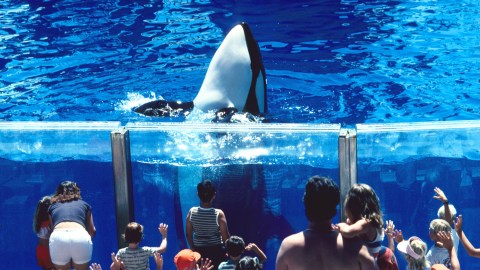

Study explains exactly why captivity is bad for orcas

Image source: ullstein bild/Getty

- Researchers present a detailed catalogue of the hardships captive orcas face and the damage done to them.

- The study draws parallels between known human chronic stresses and entertainment and research facility conditions.

- The evidence offers a damning response to perplexed apologies offered by proprietors of such parks, aquariums, and zoos when an orca dies.

Free Willycame out in 1993, followed 20 years later by the disturbing Blackfish. One fiction, one fact, and both depicting the cruelty of keeping marine animals — in this case, the orcas — in captivity. Intuitively, it seems obvious that imprisoning these deep-sea creatures for human entertainment in marine parks and aquariums is inhumane, and a growing body of research agrees. Now a new study, titled “The Harmful Effects of Captivity and Chronic Stress on the Well-Being of Orcas,” focuses on identifying the links between specific conditions in such environments and the greater incidence of illness and early mortality seen in captive orcas.

Each time an orca dies, proprietors of such facilities express surprise and “confoundment,” says neuroscientist Lori Marino, lead author of the paper — it was published in the Journal of Veterinary Behavior on June 15 — in an email to Big Think. “The message to the public is that there is no connection between living in concrete tanks and mortality,” she writes. “But this paper and others before it show that this is far from the case. We should not be surprised when a young orca dies in a tank. We know why; it is not a mystery. It is explainable by well-known mechanisms of how chronic stress effects health. We wanted to finally put an end to the false debate about the welfare of orcas in concrete tanks and also provide the potential mechanism for the high morbidity and mortality in captive orcas. I hope we did both.”

Image source: A_Lesik / Shutterstock

About Marino’s work

Marino is the founder of the Kimmela Center for Animal Advocacy, whose mission is to bring together the animal advocacy movement and academic researchers to make the scientific, moral, and legal case for animal rights. Her work extends beyond marine animals — and includes research on gorillas and farm animals — in over 130 peer-reviewed papers, book chapters, and magazine articles. This self-described “scientist-advocate” for animals has been cited by National Geographic as an “innovator,” and she was co-author of the original landmark research published in 2001 in which a pair of young dolphins demonstrated self-awareness by interacting with their reflections in mirrors.

Marino also appeared in Blackfish, and is currently president of the Whale Sanctuary Project, an ambitious endeavor aimed at establishing seaside sanctuaries for orcas and belugas released from entertainment facilities.

Marino was a scientific advisor for the Nonhuman Rights Project’s effort to award chimpanzees Tommy and Kiko legal personhood, an important step forward for animals and a case we’ve previously written about. “There is abundant, unquestionable evidence for personhood for animals,” Marino told National Geographic. “Person doesn’t mean ‘human.’ Human is the biological term that describes us as a species. ‘Person,’ though, is about the kind of beings we are: sentient and conscious. That applies to most animals, too. They are persons or should be legally.”

Marino is no longer involved with direct research on animals. She was hit hard by the early deaths of the dolphins she’d worked with in the mirror study, and soon after learned about “the underworld of dolphin and whale captivity and the Taiji drive hunts in Japan,” and that they were financed by marine parks all over the world, including the U.S. “I gave up working with captive dolphins,” she recalls, and committed herself instead to their advocacy. “I felt that as a marine mammal scientist it was my responsibility to use my expertise for the good of those animals I learned so much from,” she writes.

Marino envisions another paper similar to the orca study looking at the effect of captive environments on belugas, who are also often held in marine parks and zoos. In addition, she and her research partner are working toward their third paper examining the medical validity of dolphin-assisted therapy (DAT), in which humans swim with dolphins. Despite claims to the contrary, the researchers’ first two publications “showed that the studies used to claim that DAT is authentic treatment for autism and other problems are too methodologically flawed to support that claim. There is currently no evidence that DAT works,” Marino writes.

Image source: Stacey Newman/Shutterstock

Orcas

The black and white Orca (Orcinus orca) is the third most-often captured cetacean after bottlenose dolphins and beluga whales. There are currently 71 orcas in captivity according to Inherently Wild, including Miami Seaquarium’s lone Southern Resident Lolita — aka, “Tokitae.”

Such orcas, the researchers of the new study state, “consistently display behavioral and physiological signs of stress and frequently succumb to premature death by infection or other health conditions.”

Orcas are dolphins with large complex brains and strong social and familial ties. They routinely range widely and dive deeply. They are self-aware, cultural beings who differentiate and identify their own groups through dialect, prey preference, group size, and many other learned traditions. They have a prolonged juvenile period of social learning and the emotional bonds between mothers and calves, as well as among other relatives, are as strong as any in the animal kingdom. They also demonstrate the capacity to grieve. While these characteristics are associated with a high degree of intelligence and social sensitivity and complexity, these characteristics also describe what natural capacities and behavior these whales need to be able to express in order to thrive. — Marino, et al

This self-awareness makes their captive plight even sadder. “Intelligence — meaning cognitive complexity — can be a liability, rather than a buffer, for these animals as they attempt to cope with life in artificial barren settings,” says Marino.

The focus of the paper

The new study is a unique collaboration among marine mammal researchers, veterinarians, and physicians. Co-authors Naomi Rose and Ingrid Visser are marine mammal biologists, Hope Ferdowsian and Veronica Slootsky are physicians specializing in human physical and psychological trauma, and Heather Rally is a veterinarian. Marino tells Big Think, “You might expect that there would be many disagreements given the wide range of expertise all of us represent but, in fact, in terms of the substantive issues the opposite was true.”

Within the paper is an encyclopedic review of the cognitive systems that orcas posses, thus establishing the “neurobiological foundations of complex psychology, emotion, and behavior.” These include:

- a large relative brain size

- an expanded neocortex

- a well-differentiated cortical cytoarchitecture

- an elaborated limbic system.

The study also looks at the conditions in which captive orcas live, and associates a long list of captive environmental factors to corresponding chronic stresses known to be harmful to humans. The Whale Sanctuary Project’s press release highlights five areas of chronic stress for orcas:

- Social: Artificially-formed social groups and frequent transfers in and out of facilities disrupt mother-calf bonds, perpetuating a cross-generational cycle of poor maternal care and negative impacts.

- Confinement: Inadequate depth and horizontal space in tanks prevent the expression of species-specific movement and lead to behavioral anomalies and physiological de-conditioning.

- Sensory disturbance: Exposure to loud artificial sounds both above and below the water surface, such as fireworks, audience noise, construction, and filtration system noise creates anxiety and sensory interruption. Additionally, the concrete tank walls create an abnormal acoustic environment.

- Lack of control: Loss of autonomy and control over daily activities leads to the well-known stress-related psychological condition known as learned helplessness, which manifests as depression, lack of motivation, impaired learning, anorexia, and eventual immunocompromise.

- Boredom: Daily monotony and lack of appropriate challenges in such a large-brained complex animal, lead to immobility (increased logging behavior on the surface), depression, irritability, and increased anxiety.

Image source: Doptis / Shutterstock

All captive orcas need is the opposite of what they have

While the methodology employed in the study has been rigorously undertaken and applied by its authors, some may say that it’s a leap to use human chronic stress to as a standard for assessing chronic stress non-humans. Marc Bekoff of Psychology Today would disagree, writing that he “couldn’t agree more with Marino’s conclusion.”

Marino herself says, “I am more convinced than ever that human-nonhuman expertise — when brought together — can be a very interesting and productive way to understand health and well-being across the board. The issues are so similar and there is no reason to not utilize the full range of expertise and insight when approaching these issues.”

As for what Marino would like to see as the study’s impact, she writes, “Follow the data! We would like the science to drive the action.” Given the comprehensive nature of the paper, she hopes the “science is an impetus for the marine mammal community to critically re-evaluate their practices and work together to provide a more natural and viable environment for captive whales.”