An ancient piece of chewing gum offers surprising insights into the human genome

Tom Björklund

- Researchers recently uncovered a piece of chewed-on birch pitch in an archaeological dig in Denmark.

- Conducting a genetic analysis of the material left in the birch pitch offered a plethora of insights into the individual who last chewed it.

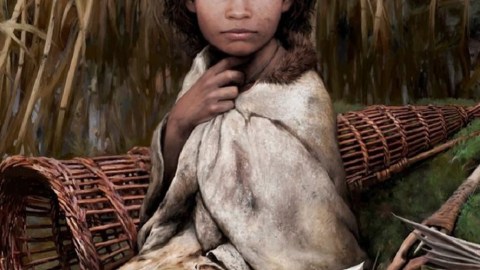

- The gum-chewer has been dubbed Lola. She lived 5,700 years ago; and she had dark skin, dark hair, and blue eyes.

Five thousand and seven hundred years ago, “Lola” — a blue-eyed woman with dark skin and hair — was chewing on a piece of pitch derived from heating birch bark. Then, this woman spit her chewing gum out into the mud on an island in Denmark that we call Syltholm today, where it was unearthed by archaeologists thousands of years later. A genetic analysis of the chewing gum has provided us with a wealth of information on this nearly six-thousand-year-old Violet Beauregarde.

This represents the first time that the human genome has been extracted from material such as this. “It is amazing to have gotten a complete ancient human genome from anything other than bone,” said lead researcher Hannes Schroeder in a statement.

“What is more,” he added, “we also retrieved DNA from oral microbes and several important human pathogens, which makes this a very valuable source of ancient DNA, especially for time periods where we have no human remains.”

In the pitch, researchers identified the DNA of the Epstein-Barr virus, which infects about 90 percent of adults. They also found DNA belonging to hazelnuts and mallards, which were likely the most recent meal that Lola had eaten before spitting out her chewing gum.

Insights into ancient peoples

The birch pitch was found on the island of Lolland (the inspiration for Lola’s name) at a site called Syltholm. “Syltholm is completely unique,” said Theis Jensen, who worked on the study for his PhD. “Almost everything is sealed in mud, which means that the preservation of organic remains is absolutely phenomenal.

“It is the biggest Stone Age site in Denmark and the archaeological finds suggest that the people who occupied the site were heavily exploiting wild resources well into the Neolithic, which is the period when farming and domesticated animals were first introduced into southern Scandinavia.”

Since Lola’s genome doesn’t show any of the markers associated with the agricultural populations that had begun to appear in this region around her time, she provides evidence for a growing idea that hunter-gatherers persisted alongside agricultural communities in northern Europe longer than previously thought.

Her genome supports additional theories on northern European peoples. For example, her dark skin bolsters the idea that northern populations only recently acquired their light-skinned adaptation to the low sunlight in the winter months. She was also lactose intolerant, which researchers believe was the norm for most humans prior to the agricultural revolution. Most mammals lose their tolerance for lactose once they’ve weaned off of their mother’s milk, but once humans began keeping cows, goats, and other dairy animals, their tolerance for lactose persisted into adulthood. As a descendent of hunter-gatherers, Lola wouldn’t have needed this adaptation.

A photo of the birch pitch used as chewing gum.

Theis Jensen

A hardworking piece of gum

These findings are encouraging for researchers focusing on ancient peoples from this part of the world. Before this study, ancient genomes were really only ever recovered from human remains, but now, scientists have another tool in their kit. Birch pitch is commonly found in archaeological sites, often with tooth imprints.

Ancient peoples used and chewed on birch pitch for a variety of reasons. It was commonly heated up to make it pliable, enabling it to be molded as an adhesive or hafting agent before it settled. Chewing the pitch may have kept it pliable as it cooled down. It also contains a natural antiseptic, and so chewing birch pitch may have been a folk medicine for dental issues. And, considering that we chew gum today for no other reason than to pass the time, it may be that ancient peoples chewed pitch for fun.

Whatever their reasons, chewed and discarded pieces of birch pitch offer us the mind-boggling option of learning what someone several thousands of years ago ate for lunch, or what the color of their hair was, their health, where their ancestors came from, and more. It’s an unlikely treasure trove of information to be found in a mere piece of gum.