The real reason Vincent van Gogh cut off his ear

- At age 35, the painter Vincent van Gogh cut off part of his ear and brought it to a brothel.

- Explanations for his self-mutilation range from psychosis to the myth of the tortured artist.

- Van Gogh saw his madness as inhibiting, not enabling, his creativity.

When the Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh was 35 years old, he cut off the lower half of his left ear with a razor blade. After bandaging his bleeding wound, he wrapped the severed ear in paper and brought it to a brothel in the French town of Arles, where he had been living and working with the artist Paul Gauguin. Van Gogh offered the ear to a woman, telling her to “keep this object carefully.”

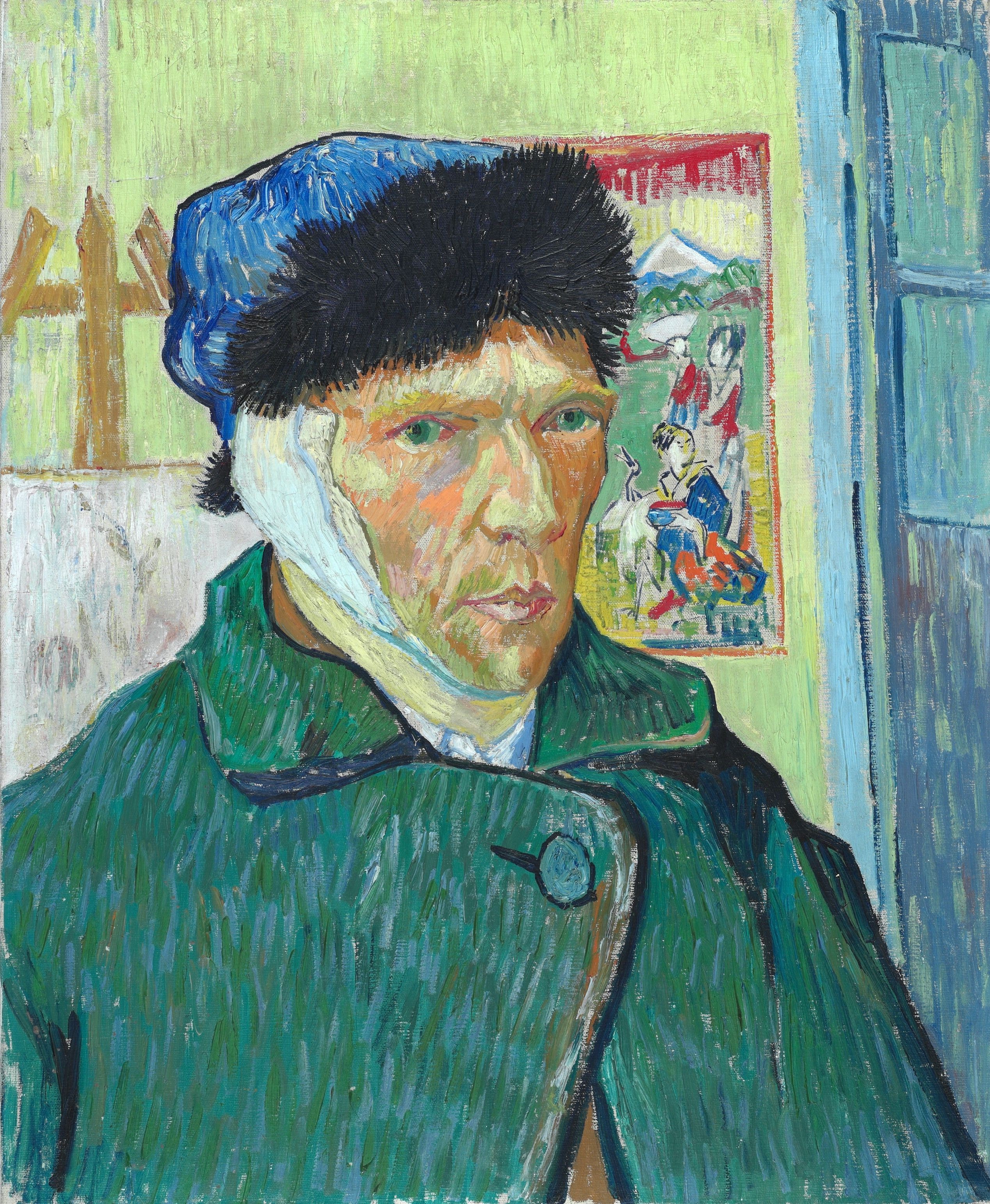

Later that evening he was found unconscious and taken to a nearby hospital. Although his severed ear was eventually brought there as well, the medical assistant taking care of van Gogh determined too much time had passed to reattach it. The painter immortalized his maimed appearance in two paintings: Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear and Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear and Pipe.

The self-mutilation of Vincent van Gogh, arguably the most famous story in all art history, has greatly contributed to his posthumous popularity. Even if you have never seen one of his paintings before, you know about the ear. But no one knows for sure why van Gogh decided to cut it off, much less why he brought it to a brothel.

While the incident did not immediately end van Gogh’s artistic career, it did mark the end of his life as an independent and semi-functional adult. Not long after being discharged from the hospital, he checked into an asylum to receive treatment for an array of undiagnosed medical conditions, many of which supposedly manifested as voices in his head.

Academic studies of van Gogh’s work are often accompanied by studies of his psychology. In a 1981 paper, W.M. Runyan, a research psychologist at the University of California-Berkeley, outlined 13 prevailing hypotheses surrounding the injury. Which are true and which are false? Is there a single explanation, or were the painter’s actions driven by a combination of factors?

13 hypotheses

About half the hypotheses listed by Runyan interpret van Gogh cutting off his ear as an unhealthy response to personal problems. For example, one explanation is that his self-mutilation was the result of his inability to express his frustration with the engagement of his brother Theo, on whom he depended, and his failure to maintain a working relationship with Gauguin, whom he admired.

The struggling van Gogh relied on Theo for financial as well as emotional support. The painter had gotten used to spending Christmas with his brother, and when he learned Theo would spend the holidays with his fiancée and her family instead, he may have hurt himself in an attempt to get Theo’s attention, make him feel sorry, and force him to come to Arles.

Another hypothesis suggests Van Gogh was trying to get the attention of a local family, the Roulins. He had previously used the family’s matriarch as a model for a painting of a woman rocking a cradle and, according to Runyan, “may have envied the love and attention [her] children received.” Crucially, her husband is said to have helped care for the painter on the night of the injury.

A more psychoanalytic hypothesis holds that van Gogh’s self-mutilation was the culmination of his attempt to suppress the physical attraction he felt towards Gauguin, with his severed ear being a phallic symbol of self-castration. It’s possible, since the Dutch word for ear is similar to the slang term for penis, but also improbable, as Van Gogh saw female prostitutes and left no mention of homosexuality in writing.

Of bulls and brothels

The other half of Runyan’s hypotheses treat Van Gogh’s self-mutilation as some kind of poetic statement, a twisted work of art that — at its core — is as meaningful as his best paintings. For instance, in a moment of ecstasy, the deeply religious painter may have wanted to act out a scene he had recently tried to paint: of Simon Peter cutting off the ear of the servant of the Jewish high priest, who had come to arrest Jesus Christ.

Alternatively, van Gogh may have wanted to reenact a bullfight. He’d seen one in Arles before and was deeply moved by them. At the end of each fight, matadors were given the ear of the bull as a prize, which they would display to the crowd before handing it to a lady of their choosing. Perhaps van Gogh, as one researcher cited by Runyan puts it, saw himself as both “the vanquished bull and the vanquisher.”

Or, instead of a bull, he may have sought to identify himself with the woman he gave his ear to. Van Gogh sympathized with prostitutes partly because they were social outcasts like him. “The whore is like meat in a butcher shop,” he had written months before the injury, possibly foreshadowing it. However, considering the woman he gave his ear to was a maid and not a prostitute, this hypothesis seems less likely.

A final possibility is that van Gogh’s self-mutilation was Oedipal in nature. Earlier in the day, writes Runyan, he had threatened Gauguin with a razor but, “under Gauguin’s powerful gaze,” desisted. Later, he might have “gratified his extraordinary resentment and hate for his father [projected onto Gauguin] by deflecting the hatred on his own person.”

The myth of the tortured artist

Because “it would be surprising to find a single explanation for any human action,” Runyan believes several hypotheses may have played a role in making van Gogh pick up the razor. For example, his decision to cut off his ear may have been inspired by bullfights, while the decision to do so around Christmastime may be tied to his brother’s engagement.

Regardless of van Gogh’s motivation, the story of his self-mutilation has cemented his legacy as the quintessential tortured artist, a label also applied to the likes of Kurt Cobain and David Foster Wallace. Because of his legacy, his self-mutilation is more often described in popular culture as a creative act than as a product of mental illness, even though this interpretation is long out of date.

In reality, madness inhibited rather than encouraged van Gogh’s creativity. “Work distracts me infinitely better than anything else,” he said of the paintings he made while at the asylum, “and if I could once really throw myself into it with all my energy that might possibly be the best remedy.” “Oh,” one of his last letters reads, “if I could have worked without this accursed disease — what things I might have done.”

Although it is difficult to assess a patient who is no longer alive, the psychiatric literature on van Gogh argues the painter likely suffered a variety of illnesses, including borderline personality disorder, the symptoms of which were worsened by alcohol abuse, malnutrition, and — possibly — lead poisoning he contracted by ingesting small samples of his paints, though this point is contested.

In light of these diagnoses, the most convincing explanation is that van Gogh’s self-mutilation was caused, as Runyan surmises, by “the perceived loss of brother’s care.” A masochist (he once asked a woman to stay with him company for as long as he could keep his hand over the flame of a candle), Van Gogh would have turned anger at his brother towards himself, starting down a path that would lead to his suicide in 1890.