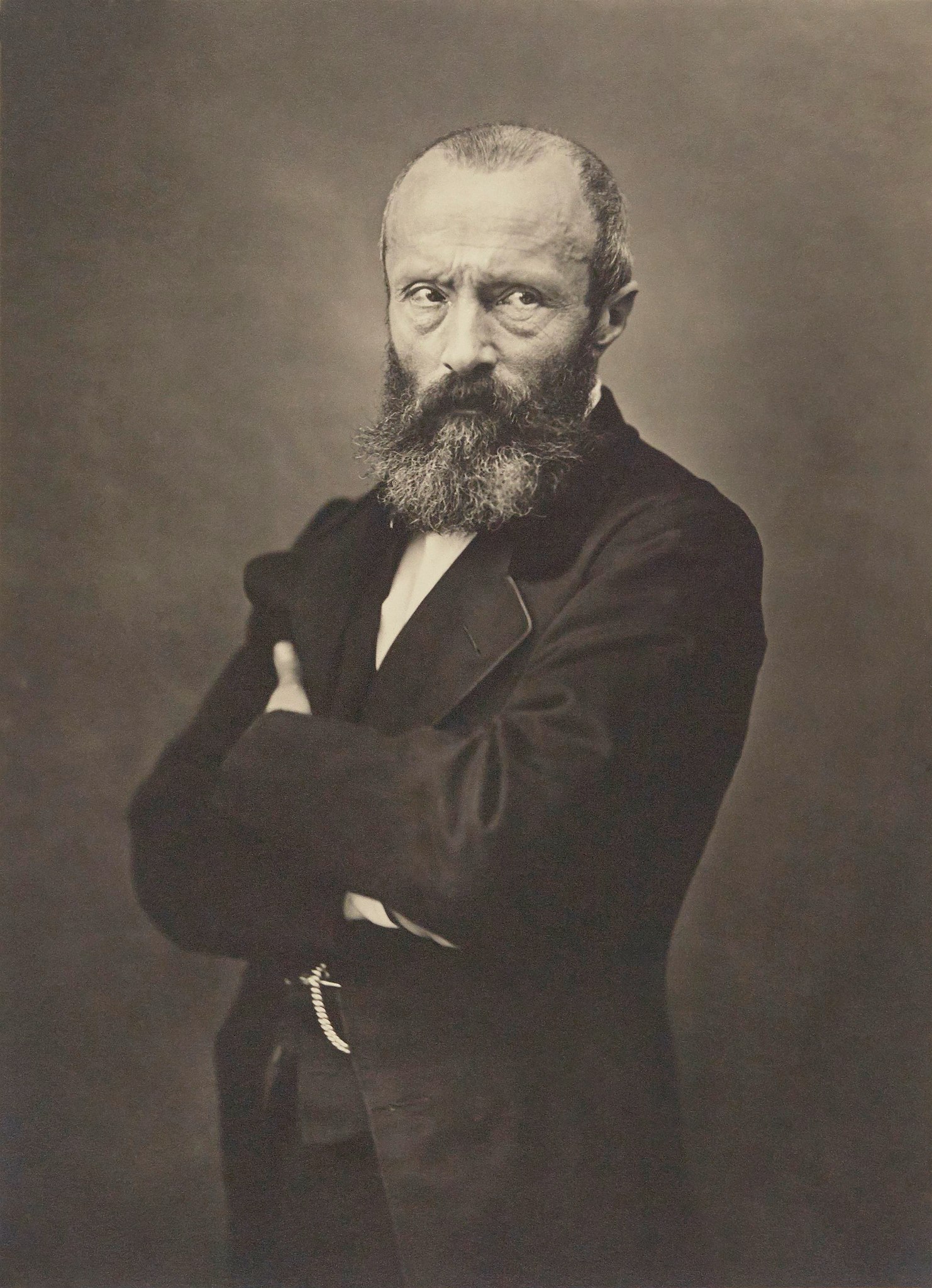

The French art critic who saved Johannes Vermeer from total obscurity

- In the 19th century, the Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer was largely forgotten by the world.

- When he died, his family had to sell many of his now-priceless paintings in order to survive.

- Thanks to the keen eye of Théophile Thoré, countless people now enjoy the beauty of his work.

When the critic and politician Théophile Thoré fled France after two of his publications were banned by the French government, he used his political exile as an excuse to conduct an extensive study of European painting. Among other places, Thoré traveled to the Low Countries to check out the work of master painters who had already been canonized. What he did not expect was to become absolutely transfixed by the genius of an artist who, at the time of his visit, was known to few and adored by fewer still.

The year was 1842. The location was the Mauritshuis, a museum in the Dutch cultural capital of the Hague. Examining its collections, Thoré stopped in front of a picture that many visitors passed by. Labelled “View of Delft,” it was a deceptively simple snapshot of the eponymous town, which lies just south of the Hague. At a glance, the “brilliance of the light, the intensity of the color, the solidity of the paint in certain parts, the effect that is both very real and nevertheless original,” reminded him of Rembrandt van Rijn. However, Rembrandt – who’d lived and worked in the nearby town of Leiden – was not the author. The person who made this painting, according to a museum catalogue, was somebody named “Jan van der Meer.”

“A dozen years ago, Jan van der Meer of Delft was almost unknown in France,” Thoré later remarked. “His name was missing from the biographies and histories of painting; his works were missing from the museums and private collections.”

From this moment on, Thoré made it his mission to give Jan van der Meer – known today as Johannes Vermeer – the recognition he deserved but never had. For his book Musées de la Hollande, Thoré searched every museum and private collection in the Netherlands for paintings by Vermeer. His devotion to the artist was admirable, bordering on obsessive. On one occasion, Thoré journeyed hundreds of miles just to obtain a photograph of a painting by Vermeer. He acquired dozens of paintings from dealers. Some of these had already been attributed to Vermeer. Others had not, though they seemed to exhibit the same qualities as “View of Delft.” Thoré visited authorities in Cologne, Dresden, Berlin and Vienna to learn if his hunches were correct. Sometimes they were. Sometimes they weren’t.

In all, the French critic claims to have recovered more than 72 paintings by Johannes Vermeer – an overzealous statement. Today’s art historians recognize fewer than 36, and doubt that the artist – unproductive in comparison to some of his contemporaries – created more than 60 in his lifetime. Still, Thoré receives credit for being the first early modern observer to perceive the quiet beauty in Vermeer’s work. Throughout his 20 years of research, he not only saved the quintessential Dutch artist from oblivion, but also laid the foundation for subsequent scholarship. To appreciate a Johannes Vermeer, in other words, is to give thanks to Théophile Thoré.

The life and death of Johannes Vermeer

For people living in the 21st century — a time in which paintings like “The Milkmaid” and “Girl with a Pearl Earring” are reproduced on posters, shirts, and overpriced tins of stroopwafels — it is hard to imagine how Vermeer ended up in the desolate state in which Thoré found him. Although Vermeer was by no means the most successful artist of his time, he was — at his pique — relatively well-known and well-to-do, at least in his native Delft. He came from a family of considerable means and moderate influence. He was recognized as a master painter by his guild when he was only 21 years old, and later served as one of its lead administrators.

Many who were close to Vermeer, from his colleagues to his father-in-law, expected him to reach great heights. Unfortunately, his upward trajectory eventually transitioned into a downward spiral. For most of his adult life, Vermeer supplanted the income he earned from his own paintings by buying and selling the work of other artists. According to his wife, Catharina, both business ventures collapsed during the Franco-Dutch War, which lasted from 1672 until 1678.

“Owing to the very great burden of his children,” Catharina wrote in a petition, “having no means of his own, he had lapsed into such decay and decadence, which he had so taken to heart that, as if he had fallen into a frenzy, in a day or day and a half he had gone from being healthy to being dead.”

When Vermeer passed away, his family was so poor that they could not even make a customary donation to the poor on his behalf. Since the painter was completely bankrupt, creditors had no choice but to confiscate his mirrors, bedsteads, and, fatefully, even his paintings. The latter, Jane Jelley says in her book, Traces of Vermeer, proved to be his widow’s “most valuable assets.” Indeed, Catharina is thought to have sold two paintings — “The Guitar Player”and “Mistress and Maid,” presumably — to a bakery in exchange for bread, under the condition that she could buy them back if she ever had enough money (she did not).

Even the painting Vermeer had considered to be his masterpiece, “The Art of Painting,” was taken out of the family’s hands. Art historians still struggle to explain what happened to Vermeer’s pictures after his passing, partly because many were wrongfully reattributed to other, more popular painters to increase their value.

Bankruptcy is not the only reason that Vermeer’s name faded from memory. As mentioned, Vermeer was not a particularly productive painter, producing far fewer pictures than other 17th century artists. Several of his paintings — including “The Art of Painting” — never left his home, preventing the artist from building a public record.

“A painter whose name seldom turned up in the sales catalogues could not become widely known,” writes Philip L. Hale points out in Vermeer and His Time, “and with so limited a number of pictures to change hands the occasions when a Vermeer would be offered would naturally be few.” When a British art historian named John Smith compiled information on Dutch artists for his 1833 catalogue of European painting, he only devoted a small paragraph to Vermeer. “This painter is so little known,” the paragraph notes, “by reason of the scarcity of his works, that it is quite inexplicable how he attained the excellence many of them exhibit.”

A master painter rediscovered

After his chance encounter with “View of Delft,” Thoré managed to track down other Vermeers, including “Little Street in Delft,” “Portrait of a Girl,” and, of course, “The Milkmaid,” which was called “The Milkwoman” in early documents. “The astounding painter!” Thoré exclaimed when he saw the now-infamous woman pouring out her milk jug — a jug that Vermeer himself had likely owned and used as a model, and which may well have been confiscated at the time of his death. “But, after Rembrandt and Frans Hals, is this van der Meer, then, one of the foremost masters of the entire Dutch School? How was it that one knew nothing of an artist who equals, if he does not surpass, Pieter de Hooch and [Gabriël] Metsu?”

Even though Vermeer’s legacy has been restored, there is much about the painter that we still don’t know. This includes his appearance. He was part of a militia group, not unlike the one Rembrandt depicted in his “Night Watch,” but there are no paintings of this group and its members. If Vermeer painted any self-portraits during his short career, they have not survived either. He mostly painted women and girls, and the handful of men in his pictures — the figures that he might have based on himself — are typically, curiously, presented facing away from the viewer. Some believe that Vermeer featured himself in “The Procuress,” though this is pure speculation.

In the end, the character of the man that was Johannes Vermeer has to be inferred from his unique style of painting – from the quiet beauty that Théophile Thoré found in “View of Delft,” and which – thanks to him – countless others have since observed in “The Milkmaid,” “Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window,” and “Girl with a Pearl Earring,” to name a few.