Stendhal syndrome: Can beautiful art make you mentally ill?

- The French author Stendhal recalled feeling mentally and physically unsettled when visiting the classical city of Florence.

- Each year, a little over a hundred museum goers are admitted into Florence’s emergency rooms for the exact same reasons.

- Is “Stendhal syndrome” a fancy name for traveller fatigue or a byproduct of some special sensitivity toward overwhelming beauty?

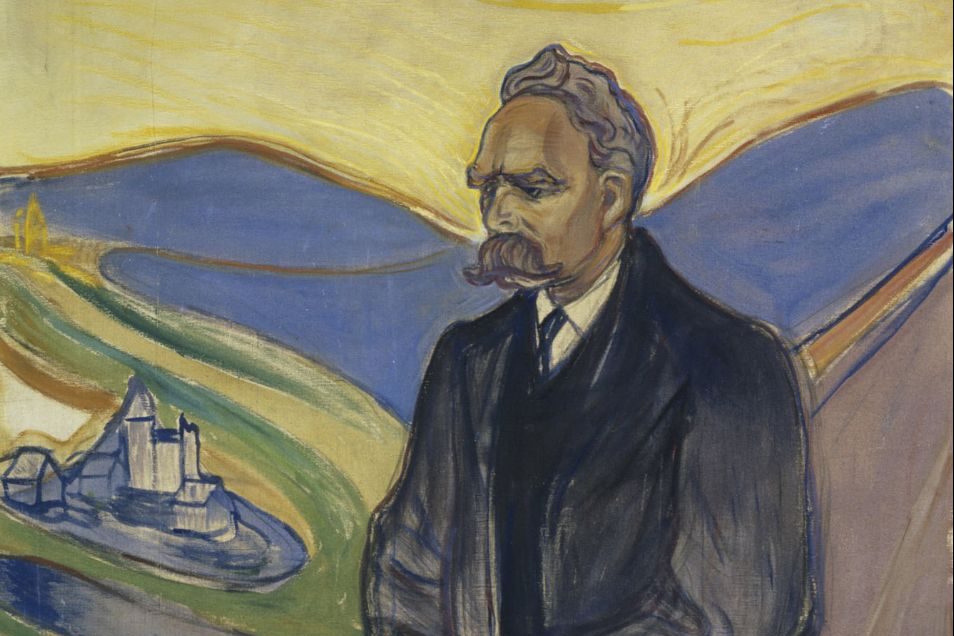

In 1817, the French author Marie-Henri Beyle, better known by his literary alias Stendhal, traveled to Florence. The purpose of this voyage was a visit to the Basilica of Santa Croce, an imposing cathedral that housed the tombs of three of the most remarkable individuals in human history: the philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli, the artist Michelangelo, and the astronomer Galileo Galilei.

Each of these three individuals had played a crucial role in the development of art and science. They had also made a powerful impact on a young Stendhal, informing the shape and substance of the novels he would later write down. For this very reason, the author felt a strong but strange feeling when he entered the Basilica and approached the burial tombs within. As he recalls in Naples and Florence: A journey from Milan to Reggio:

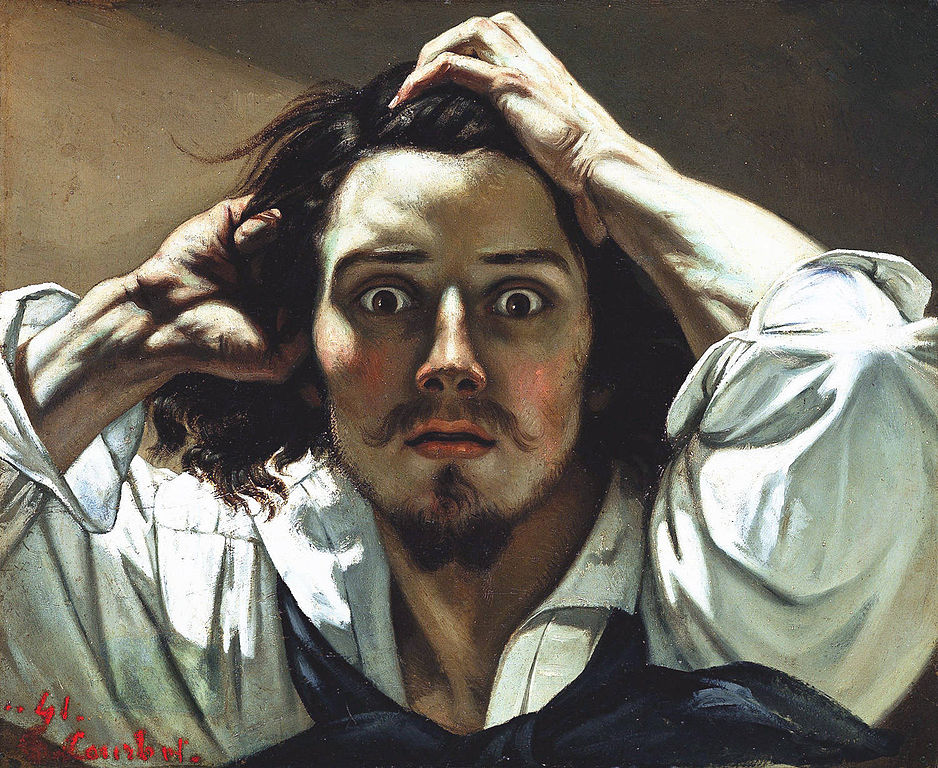

“I was in a sort of ecstasy, from the idea of being in Florence, close to the great men whose tombs I had seen. Absorbed in the contemplation of sublime… I reached the point where one encounters celestial sensations… Everything spoke so vividly to my soul. Ah, if I could only forget. I had palpitations of the heart, what in Berlin they call ‘nerves.’ Life was drained from me. I walked with the fear of falling.”

Stendhal is not the only person to have experienced a visceral reaction from being in the presence of art and artifacts; in 2019, the New York Times devoted an entire article to surveying health-related incidents reported by the major museums of Florence. Nor was Stendhal the first to put his experience into words; two centuries ago, Longinus described a similarly overwhelming sensation brought on by exposure to beauty, the Sublime.

Regardless, it was Stendhal whose name would ultimately become associated with this condition as Italian scientists and culture critics, no doubt flattered by the author’s description of their national treasures, coined the term “Stendhal syndrome.” While the tantalizing notion that art can make us physically or mentally ill is certainly enticing, scientists still aren’t sure what this syndrome actually is, let alone whether or not it even exists.

The history of Stendhal syndrome

Stendhal syndrome was born in Italy, and to this day, many of the most comprehensive studies on the subject have been conducted in this country. In 1989, the Santa Maria Nuova hospital in Florence published a write-up of all 106 emergency cases that had been brought in by ambulance from museums and galleries around the city. Reported symptoms ranged from disorientation and dizziness to heart palpitations, hallucination, and loss of identity.

Italian researchers quickly pushed their nationalistic interpretation of Stendhal syndrome onto the rest of the academic world. Santa Maria Nuova hospital listed “an impressionable personality” as a precipitating factor, along with “the stress of travel and the encounter with a city like Florence, haunted by the ghosts of the great, death and the perspective of history.” Patients were advised to leave Italy so their eyes could readjust to earthly imperfection.

Subsequent research papers contested the hospital’s notion that the syndrome was connected to a specific place. Surely Italian art was not the only art capable of evoking psychosomatic responses. In France, Michel Proust suffered from constant asthma attacks while working on In Search of Lost Time, and in Russia, Fyodor Dostoevsky became so fixated on a religious painting that his wife worried he would slip into an epileptic fit.

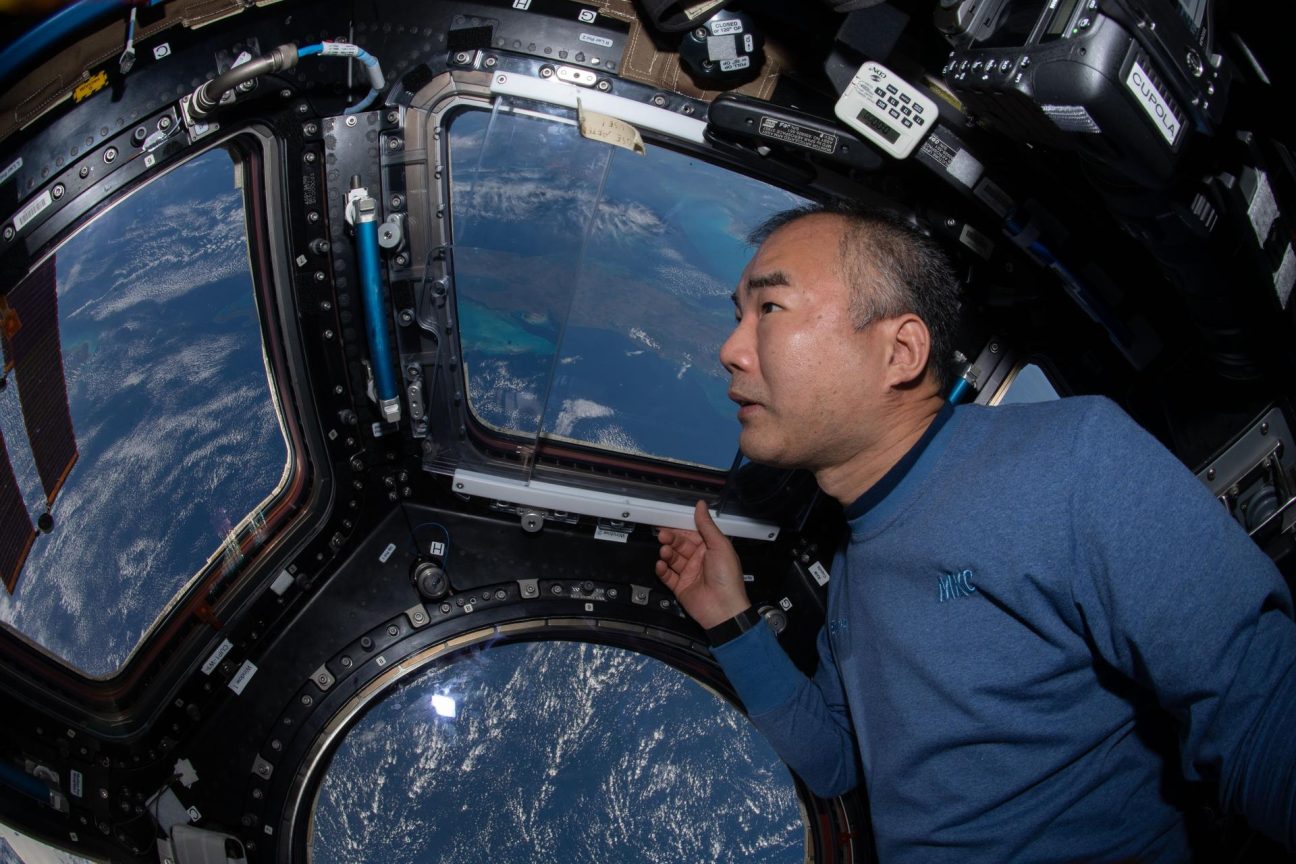

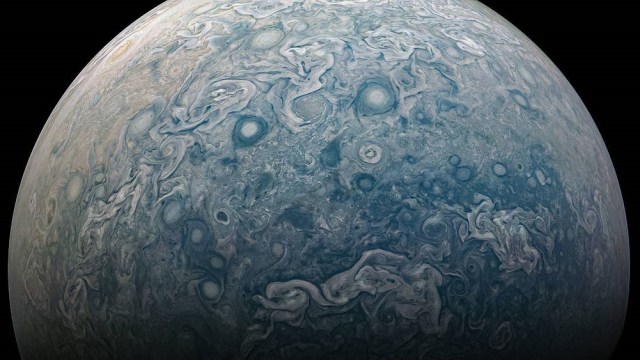

Nor is Stendhal syndrome tied to Italian Renaissance, for that matter. The way in which some primary sources relate what many ancient pilgrims felt when they finally arrived at their spiritual destinations is eerily similar to what’s found in the hospital report; on average, the city of Jerusalem treats as many people with inexplicable medical problems — referred to as “Jerusalem syndrome” — as Florence’s biggest museums.

Today, aestheticians and neuroscientists agree that Stendhal syndrome — far from being confined to the heartland of Italy — is actually a universal experience brought about by our shared ability to appreciate beauty. “While the object of beauty may change from one person to another,” one recent survey of scientific literature on the syndrome announced, “the awe and the thrill experienced by an enthralled beholder remains the same.”

Possible explanations

A 2017 article from Psychology and Cognitive Sciences – Open Journal defined the syndrome as “a rare psychiatric condition characterized by a state of dizziness, panic, paranoia or madness caused by being exposed to artistic or historical artifacts.” It then proceeds to list off the radically different but equally viable explanations for Stendhal syndrome that have been put forward over the past decades.

One of these holds that the symptoms attributed to the syndrome are actually a result of physical exhaustion. Traversing one or more museums in a day requires large amounts of energy, especially when you are out of shape or suffering from a medical condition. Considering that most of the people who have checked into Florence’s emergency rooms were tourists with jam-packed schedules, this theory is quite plausible.

Some believe that Stendhal syndrome has less to do with the quality of art and more with the unique position of the beholder, usually a tourist who traveled far and wide to see a place, person, or artwork. In their book, The Geography of Tourism and Recreation, C. Michael Hall and Stephen J. Page look at travel as a process of self-actualization, one that frequently puts mentally stable individuals in a more vulnerable, susceptible state of mind, making them prone to emotional outbursts.

However mundane these explanations might be, there remains something irresistible about the idea that something could be so beautiful that its perception causes us pain and madness. Proust and Dostoevsky interpreted their respective medical conditions as the unfortunate byproducts of their ability to observe reality in greater detail and with greater intensity than those around them, the same ability that enabled them to write their novels.

In theory, it makes sense that someone who appreciates art would be more impressed by, say, Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa than someone who knows nothing about paintings. However, further research is needed to find out just how these responses are processed inside our brains. Until then, all we can say with relative certainty is that individuals from classical or religious backgrounds are at greater risk of contracting Stendhal syndrome when visiting Florence.