The secret history of 7 common words

- Words evolve as they drift into new eras, environments, and social realities.

- Everyday words often hide histories revealing a time when people’s views of the world, the cosmos, and each other were profoundly different from our own.

- Here are seven such words and what they tell us about our ancestors.

Words aren’t born as fossils to be unearthed in a dictionary. Like any species of plant or animal, they live and evolve in a bid to survive the eras and environments they encounter. Some change remarkably little, some die off entirely, and some adapt until they are no longer recognizable from their forebears.

Many of these lineages can be fairly straightforward — a Latin word evolves into a French word evolves into an English one. But others can reveal unusual stories of a time when the people using them viewed the world, each other, and even the cosmos very differently than we do today.

Here are seven such words and the secret histories they tell.*

1. Alcohol

Alcohol comes from al-kuhul, a loanword from Arabic meaning “the kohl.” Kohl is a cosmetic used as an eyeliner and sun protectant. While still worn in many cultures today, it’s perhaps best-known in the Western world for its association with the ancient Egyptians, who were famously depicted wearing it on tomb murals and sarcophagi lids.

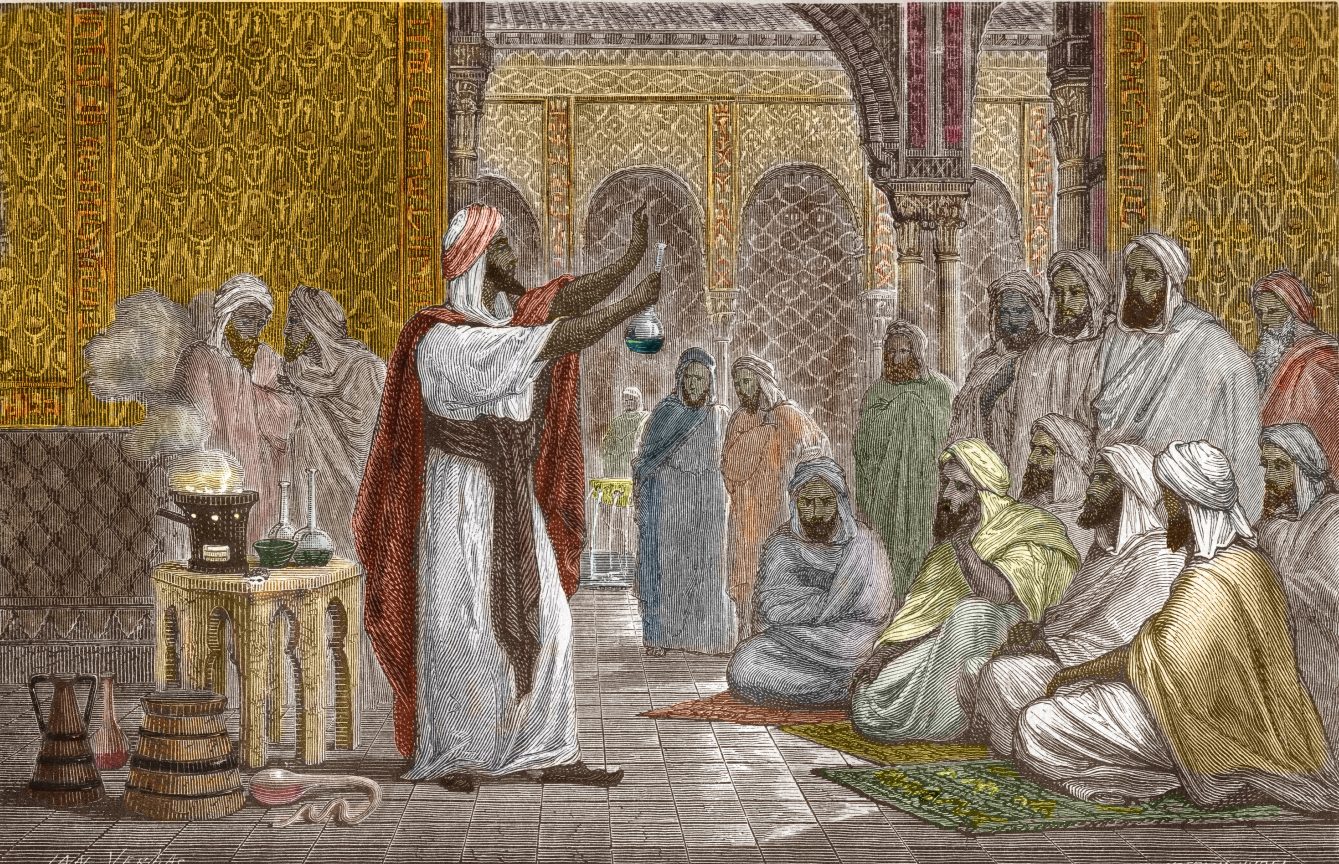

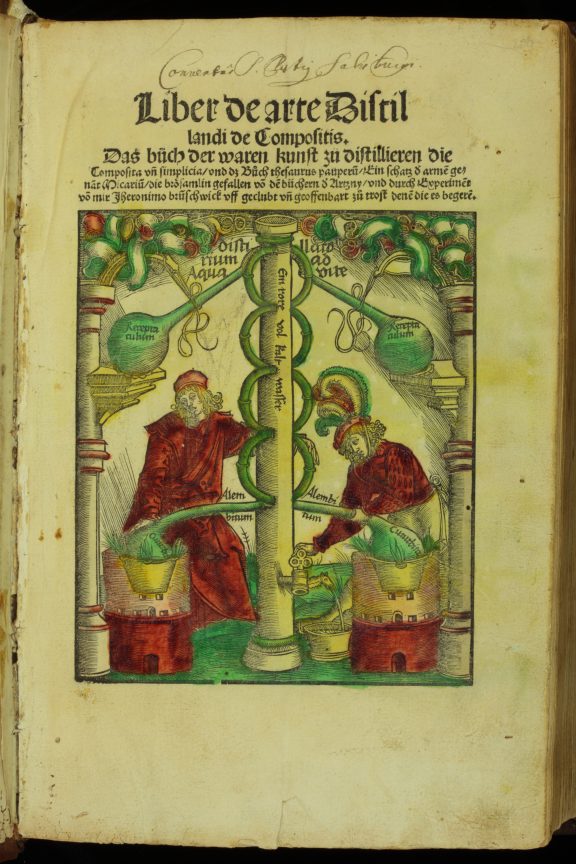

So how did a fab cosmetic come to be associated with an antiseptic and the world’s second-favorite drug? Traditionally, kohl was produced by pulverizing the mineral stibnite into a fine powder, and sometimes Arabic alchemists would further refine the powder through sublimation — that is, heating the solid to the point that it becomes a vapor. In fact, these alchemists invented the stills later used to distill spirits.

By the late 1600s, Europeans were using alcohol to refer to any sublimated substance. It wouldn’t come to mean boozy spirits until the mid-1700s.

2. Whiskey

Once Europeans got a hold of the distillation process, they aimed for something a little more grandiose than glam eyeliner: immortality.

To the medieval European mind, the world was in a continual decline from its golden age. People were less vigorous, food less nutritious, and the land more desolate and diseased. This pessimistic worldview led many to search for a means to restore their vitality to match biblical figures like the super-senescent Methuselah.

Explorers searched for legendary places such as the Fountain of Youth, and doctors might have prescribed elderly patients foods related to childhood, such as breast milk. In the same vein, alchemists turned to distillation. They theorized the process could concentrate the meager nutritional value of everyday foods into an elixir that would revitalize the human body to its Edenic state. They called this hypothetical superfood aqua vitae, or “the water of life.”

What does this have to do with whiskey? When the concept traveled to the British Isles, aqua vitae translated into the Irish Gaelic uisce beatha. Whiskey is a shortened form of this translation. (Uisce is pronounced “ish-kah.” Say it aloud, and you can feel how the windy “ish” and the thumping “kah” shifted into “whis-key” over time. The beatha — pronounced “bah-hah” — eventually dropped off in English.)

As for the search for immortality, it eventually petered out, but the belief that liquors had healing properties persisted for centuries. Even as late as the early 20th century, pharmacists still stockpiled whiskey, brandy, and gin to fulfill medical prescriptions. In fact, during prohibition, it was a handy legal loophole for getting a drink in the U.S.

3. Scapegoat

Scapegoat means “one who shoulders the blame for others,” but it originally denoted a sacrificial goat sent into the wilderness as part of an ancient atonement ritual on Yom Kippur (Leviticus 16). The word was coined by William Tyndale for his English translation of the Bible — an undertaking that saw him become a sacrifice of sorts when he was executed for heresy by the Roman Catholic Church.

Tyndale’s scapegoat is a faithful translation of the Vulgate Latin Bible’s caper emissarius. The Latin word for “goat” is caper, and it can still be found in the scientific names of many goat species today. However, the Vulgate Latin is a translation of the Hebrew azazel, and here’s where things take a turn because azazel may not mean “goat” at all.

It’s tricky because there are several possible translations. In some readings, azazel could be read as ‘ez ozel (“goat that departs” or “that which is sent away”). In others, it could be the name of the hellish wilderness the goat was sent to. The original text says there are two goats, one “for Yahweh” (that is, God) and the other destined “for Azazel.” Still other readings cast Azazel as a demon — the idea being that the goat would serve as a vessel, one that bore the people’s sins to their impure source.

This demon also appears in the apocryphal Book of Enoch, where he plays the role of a sin-gifting Prometheus. He teaches humans how to forge swords and shields, find precious stones, and — in an interesting connection to our first word — make kohl eyeliner. When these gifts lead to ungodly acts, Azazel is punished by being bound and cast into darkness.

In later apocalypses and demonologies, Azazel would be associated with the demon Samael (himself a precursor to Satan). This makes scapegoat part of a long-standing tradition connecting demons with goats, one that has continued through the centuries in religious iconography, romantic art, and, of course, horror movies.

4. Assassin

Assassin is a common word today less for rampant political slayings and more for its overuse as a storytelling device. But when the word was first devised, that relationship was reversed.

Its Arabic equivalent, hashīshīn, was initially a nickname for members of a religious-political Islamic movement. Known properly as the Nizārī Ismāʿīliyyah, the sect conflicted with neighboring caliphates throughout the 12th and 13th centuries. When direct conflict wasn’t an option, they would infiltrate the households of prominent enemy figures and murder them.

How did they get the nickname hashīshīns? The root of the word, hashish, technically translates as “dry herb” but is also the earliest known street name for cannabis. A popular belief was that the sect’s leaders used the drug to induce visions of paradise in converts. This made them more pliable before being sent on their nightmarish assignments.

It’s worth noting that there’s no historical evidence that the Nizārīs had a particular fondness for cannabis or used it for brainwashing purposes. It’s likely a form of propaganda cooked up by their enemies. But considering their enemies were on the pointy end of that murderous relationship, it’s little surprise the perspective wasn’t fair and balanced.

Stories of the Nizārīs would catch the attention of European Crusaders, who retold them at home, where they grew in popularity. By the 1500s, the word had morphed into the medieval French and Italian assissini and assassini, respectively.

5. Sycophant

Sycophant comes from the Greek sykophantes. It means “slanderer,” but a literal translation of the word’s roots (sykon and phainein) is “the one who shows the figs.”

In 6th-century Athens, it was illegal to export foods other than olives from the territory. This made goods like figs contraband that smugglers would sneak out of the territory for extra profit. Sometimes, snitches would sell out these smugglers to the authorities, and they would be reputed as “one who showed the figs.” Basically, they were known as a narc on those ancient Greek streets.

“If it was part of his purpose to ingratiate himself with the authorities, he was close to being a sycophant in the modern sense of the word,” Robin Waterfield writes in his book Why Socrates Died.

But this account is not considered substantiated by the Oxford English Dictionary. It provides an alternative history in which “showing the figs” was a vulgar gesture made by sticking the thumb between two fingers. In ancient Greece, the fig was symbolic of a vagina, and when you stick the thumb between — well, you see where this is going.

According to Oxford, politicians would publicly scorn this uncouth gesture while privately encouraging their followers to taunt their opponents with it. The toadies who did so to endear themselves to these two-faced politicians were belittled as one who shows the figs — effectively, a brown noser.

Whichever history is true, it’s interesting — and a little disheartening — to see that while the words may have changed, the political realities remain steadfast.

6. Glamour

Read the word glamour, and your mind probably conjures images of magazine covers, the posh rockin’ of David Bowie, or starlets ascending stairways in sparkling dresses. You probably don’t think about sentence structure, subject-verb agreement, and pedants loudly decrying that literally no longer means “literally.”

But both glamour and grammar share an affiliation with the magical. Grammar came to English from the Old French gramaire, meaning “learning.” In the Middle Ages, when most of the population was illiterate, books and learning were exclusive to the upper classes. And because such learnings included astrology and alchemy, grammar took on a secondary meaning of occult knowledge.

It’s this second meaning that found its way to Scotland as gramarye, or “magic, enchantment, or spell.” That Scottish word eventually evolved into glamour, while grammar settled into the study of language, as reading and learning spread more widely through English culture.

7. Gadzooks

Gadzooks isn’t a common word anymore. Fair enough. But this one is too good to pass up, because there was a time when you didn’t want a mother, schoolteacher, or priest within earshot when these foul phonemes crossed your lips.

Returning to the medieval mindset, obscene language was a very different breed. A map could direct you to a glade called “Fuckinggrove,” and no one would glance twice. If anything, the name was a selling point. But take the Lord’s name in vain, swear by him flippantly, or request He damn someone to hell, and you’ll find yourself outside the bounds of polite society.

In fact, it’s this Middle Age link between religion and vulgarity that gave us many of our contemporary euphemisms: swearing, profanity, and curse words.

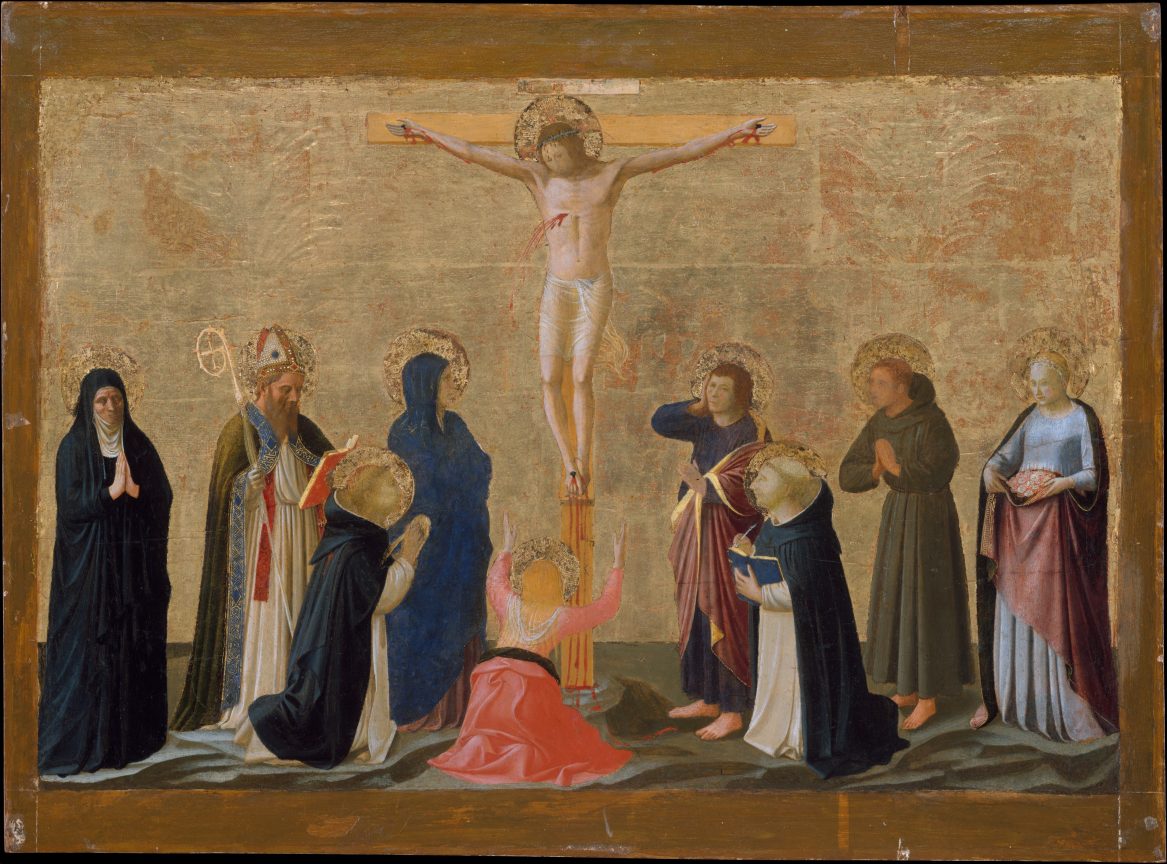

What does this have to do with gadzooks? As linguist John McWhorter points out in Nine Nasty Words, a curious habit of medieval profanity was to swear on Jesus’ or God’s body parts, such as the “archaic-sounding eruptions” of By God’s nails and By God’s arms. Gadzooks is one such expression, coming from the equally archaic By God’s hooks (that is, the nails of Christ’s crucifixion). Another is zounds, which is derived from By God’s wounds (again referencing the crucifixion).

And if you’re wondering how gadzooks came from God’s hooks, know that the “gad” comes from egad, a workaround for exclaiming “God!” It’s part of a whole history of words designed to take the Lord’s name in vain without taking the name. Others include cripes (Christ), jeez (Jesus), and jeepers creepers (Jesus Christ). How medieval people thought they were fooling an omniscient being with this coded language is anyone’s guess.

Look and you shall find

Much as a whale’s physiology divulges telltale signs of its terrestrial lineage to a biologist, once you begin looking for these hidden histories, you’ll find them everywhere. In this article alone, I had to pass over bless and its origins in pagan blood rituals; how sarcophagus came from a belief that tombs dissolved flesh; and, of course, the many mysteries of the F-word.

What are your favorite etymologies, and what do they teach you about history?

*Hat tip to Online Etymology Dictionary, which proved an indispensable resource.