How to paint like Rembrandt, according to a professional portrait artist

- From the Renaissance until the invention of the camera, portrait painting was Western Europe’s premier artform.

- In his book, Practical Portrait Painting, professional artist Frank Slater attempts to make his intimidating craft more accessible to future generations of painters.

- Slater takes his readers on a crash course throughout art history, explaining what makes the painters of each century unique.

Following the Renaissance, portrait painting cemented itself as one of the richest and most prestigious artforms in the Western world. It retained this status for centuries until the invention of the camera, which could recreate a person’s likeness more quickly and with greater accuracy than even the most skilled of human hands.

That is a shame because, at its core, portraiture is not really about copying a person’s outward appearance. As artist Frank Slater explains in his 1989 book Practical Portrait Painting, a talented portrait painter is able to use their artistic license to reveal the inward appearance of the subject or sitter: their psychology, character, and — for lack of a better word — essence.

“That,” writes Slater, “is the fascinating part of the job — everyone is utterly different. There may be similarity now and again in the structure of type, but the essence, the particular personality of every human being, is unique and a good [portrait] captures that quality.” His book not only shows you how to become a painter yourself but also how to understand and evaluate the work of other artists.

Slater attended the Royal Academy in London, where he learned from exceptional but little-known craftsmen such as Ernest Jackson and Walter Sickert, the latter of whom worked under the guidance of Edgar Degas (and was once suspected of having been Jack the Ripper). Slater was the last of a dying breed and knew it. He wrote Practical Portrait Painting in the hope of making his vocation more accessible and appealing to future generations.

Direct vs. indirect portraiture

According to Slater, there are two ways of painting a portrait: directly and indirectly. Those who paint indirectly cut the process up into sequential steps. They start with an outline, constructing the shape of the head and carefully mapping out the relationships between various facial features. This ensures the portrait will reflect the sitter’s outward appearance.

Those who paint directly approach portrait painting as a single, uninterrupted process. Where indirect painters place color atop their preexisting construction, direct painters construct through color, building the face as they go along. Direct painters work quickly and boldly, relying on instinct and feeling rather than reason and judgment.

Both methods have advantages and disadvantages. Direct painters sacrifice security in exchange for freedom. Bold, spontaneous strokes make their portraits look fresher and livelier than those that were meticulously planned. But spontaneity can also lead to carelessness, causing inescapable problems further down the road.

“During the first sitting,” Slater writes of the direct painting method, “you feel like a god. There is your blank canvas and you can paint as you please, with nothing to interfere with your complete freedom. But when you come to the second and third sitting, you will not be so free. Your previous work will affect every touch you add.”

Indirect painters, by contrast, sacrifice freedom in exchange for security. This is not as undesirable as it sounds — far from it actually, as technique and thorough understanding of light, anatomy, and musculature are the basis of any great portrait regardless of the style. Before Picasso could master cubism, he first had to learn how to paint like the old masters.

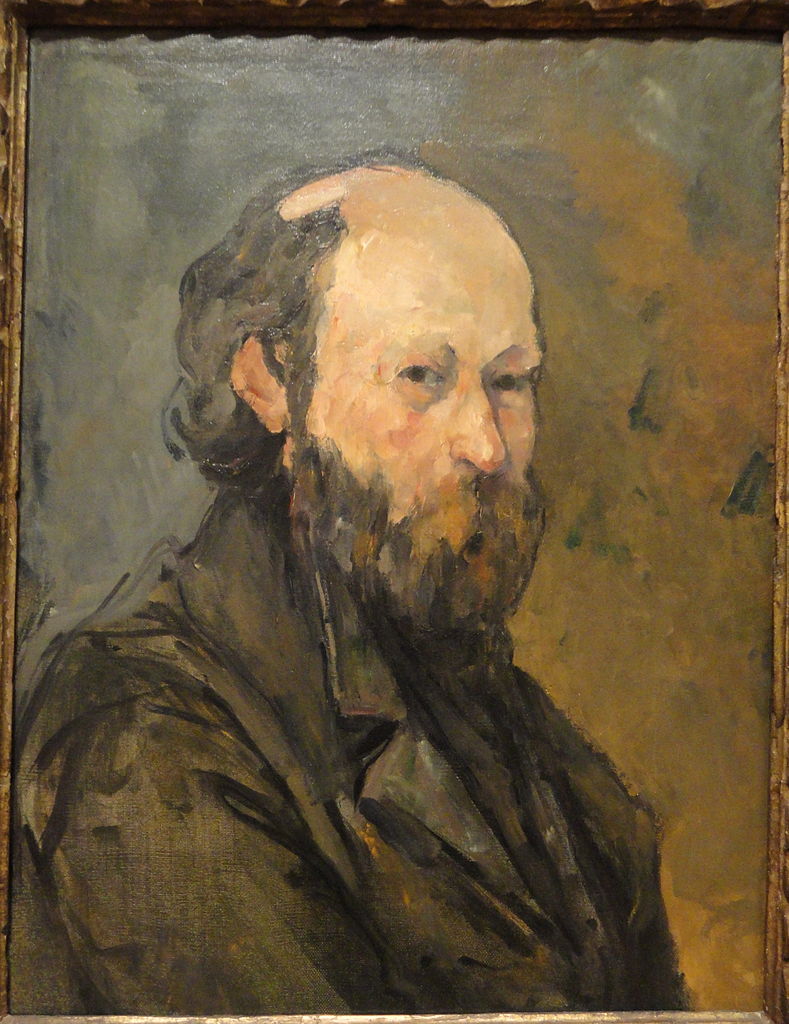

Up until recently, indirect painting was the norm. Modern artists, from Cézanne to Matisse, have demonstrated the value of direct painting. “A painting,” says Slater, “is not a drawing which is then filled in with color. Painting is relating one color value to another; painting is done with a brush; painting is not concerned with rigid outlines.”

Direct painting also allows for a certain flexibility that indirect painting could never accommodate. Practical Portrait Painting reminds its readers that sitters are living human beings who can vary greatly from one sitting to the next, and that “you do not want to be tied down too soon to hard outlines, carefully laid down at the very beginning of the picture.”

The act of portrait painting

The actual process of painting a portrait is as important to achieving a satisfying result as the knowledge and technique that inform this process. Slater advises painters to work on their paintings in a space which has good and consistent lighting, so that they will be able to see both the face of their sitter and the construction of their own portrait clearly.

Consider also the medium with which you will be working. If the primary objective is simply to practice, pencil is the way to go. Its thin lines encourage artists to select only those aspects of the sitter that are most important to both their inward and outward appearance. Charcoal can be great for studies, too, but as a medium it is much more difficult to handle than pencil.

Artists working with charcoal must be careful not to make their drawings too “photographic” by focusing on tone. Slater points to American artist John Singer Sargent, whose earlier drawings were essentially paintings made with charcoal, as an example to be avoided. Still, charcoal has a rich, deep quality that also produces subtle effects, allowing artists to record details that pencils cannot.

Portrait painting not only requires understanding of the face, but the entire human body and specifically the neck and shoulders. Da Vinci made portraits where the eyes, head, and neck were all turned in different directions. The graceful impression this creates is suitable for a fair lady like the Mona Lisa but not for, say, a rugged farmer with a downright manner.

To that end, Slater writes that a portrait painter is not only an artist but also a psychologist. Just as they need to understand the shape of the skull in order to convincingly paint a head, so too do they need to understand the meaning of a particular impression before it can be reproduced on canvas. Portrait painters, like fiction writers, must be able to empathize with people from all walks of life.

Even clothing requires careful study. Too often painters turn out a detailed head only to render the sitter’s clothes with broad strokes and general outlines. Slater says this approach produces a painting that is half-finished. Artists must understand how clothing folds, creases, and reshapes the body underneath. Most suits, for instance, are designed specifically to conceal the wearer’s figure.

The philosophy of portraiture

Unless you studied art history in college, it can be difficult to articulate how one style of painting differs from another. In Practical Portrait Painting, Slater takes his readers on a crash course through hundreds of years of art history, sharing what it was that, in his own opinion, made the great artists of each period so unique.

Slater admires Hans Holbein, painter of The Ambassadors, for his simplicity. Many of Holbein’s portraits feature little visual information, but they are not simplistic. Instead, the German painter showed himself to be master at selection, including only details that were absolutely necessary to the picture. What most artists do with a hundred strokes, Holbein could do with only one.

Slater’s all-time favorite painter is one that most people probably haven’t heard of: Augustus John. John veered toward the more experimental side of the spectrum, using broken color, expressive brush strokes, and exaggerated shapes. Though his portraits are not nearly as faithful as those of, say, Sargent, they are consistently better at conveying the sitter’s personality.

As you might be able to tell, Slater had a bone to pick with Sargent. Sargent was an exceptional craftsman. He was also the most commercially successful of his time, mostly due to the fact that his delicate and dignified style flattered the egos of the tycoons, politicians, and socialites he painted. As a result, one might argue that his work is closer to advertisement than Art with a capital A.

This is noticeable in the way Sargent painted the hands of female sitters, which he lengthened to make them more elegant. But, counters Slater, “there can be more real beauty in the observation of character.” Dutch artists were known for their interest in the common man. Whereas Michelangelo depicted gods and Sargent millionaires, Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Hals also painted farmers, workers, and tramps.

Worse than flattery was sentimentality, embodied in the work of artists like Jean-Baptiste Greuze. “Sentimentality,” states Slater, “is the refusal to admit the truth, an inability to face facts, and an attempt to cover up reality in a golden haze of false values. [In Greuze’s time] anything disagreeable or unpleasant should not be mentioned… and this had its corresponding effect on the Arts.”

This is, at the end of the day, a matter of personal taste. Still, Practical Portrait Painting makes a compelling case for why a truthful depiction of a sitter’s inward appearance should be the portrait painter’s ultimate objective. The passage below, taken directly from Slater’s book, reiterates this conclusion with particular effectiveness:

“I remember reading a biography of Marie Antoinette, illustrated with portraits of her by Mme. Le Brun and other court painters. They showed the picture of an insipid nonentity, without individuality, and it was impossible to form any real judgment of what she looked like. The last illustration was a rapid drawing done by [Jacques-Louis] David. It showed with brilliant economy of line, but absolute truthfulness, the figure of a woman seated on the back of a tumbril on the way to the guillotine. Stripped of her finery, without her elaborate coiffure, in a coarse shift and hair pushed under a mob-cap, she had more dignity and more real beauty than in all the court portraits. David saw through, and had no reason to hide it. At last I could see what Marie Antoinette really looked like.”