Paint is made up of many different components, each fulfilling a different function. There’s the medium or binder, which alters the paint’s properties by making it thicker or thinner or extending its drying time. There’s the solvent, which can be added to prevent the formation of clumps and globs. Last but not least, there are pigments, which give paint its opaqueness and, crucially, color.

Nowadays, most artists use synthetic pigments. These are mass-produced and made from acids, petroleum, or other chemicals. This is only a recent development, however. For most of art history, artists had to use biological pigments derived from minerals or clay.

Generally speaking, biological pigments are much more difficult to obtain than synthetic ones. A prime example is the color blue, long coveted because it rarely appears in nature. Another example is tyrian purple, a textile dye once used to color the robes of Roman emperors. Its only source was the mucus secreted by species of Murex shellfish living off the coast of Tyre. For every 1.5 grams of dye, 12,000 shellfish had to be crushed.

Most art lovers are not interested in learning about pigments, which — like easels, brushes, or canvasses — are just tools, and not nearly as meaningful as the masterpieces they helped create. In reality, however, pigments had a massive influence on the course of art history. The discovery of new pigments dictated how painters arranged their pallet, as did the eventual loss of other pigments. Color itself was also highly symbolic, often in ways related to its production process.

“It’s important not to overlook this material side of painting,” Lola Sanchez-Jauregui, a curatorial fellow at the Harvard Art Museums in Cambridge told Hyperallergic in an article about the blue color called lapis lazuli. She added that “viewing these tools will help people approach the paintings from a new point of view.”

Lapis lazuli: a pigment made from gemstone

Lapis lazuli, also known as ultramarine, is a deep blue pigment made by grinding down the eponymous precious stone into a soft powder. Human interest in the stone goes back millennia. As early as 7570 BC, members of the Indus Valley civilization incorporated lapis lazuli into their bracelets and arrowheads.

It did not take long before people started using lapis lazuli in painting, too. In 2006, microscopic analysis of a Bronze Age wall painting from the Mycenaean city of Gla revealed the pigment was mixed with red iron to create an equally deep purple. Lapis lazuli became especially popular during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, when it was used to paint the robes of religious figures.

Limited supply and growing demand meant that, for a long time, the blue pigment was more precious than gold. The vast majority of lapis lazuli was mined in a single place: the Kockha river valley of Badakhshan province, located in northeastern Afghanistan. To this day, the stone plays an important role in the local economy as well as politics, with illegal mining operations having contributed to the rise of the Taliban in the late 1990s.

European painters valued the pigment for its color, which is stronger and deeper than any other shade of blue on the market. Its inclusion could make a mediocre painting good, and a good painting great. Many attribute the lasting success of Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring to the titular pearl, but the girl’s lapis lazuli-colored turban, accentuated by the yellow of her dress, is just as mesmerizing. The use of lapis lazuli also compares the unnamed sitter to the Virgin Mary.

Vermeer diluted his pigment so as not to have it overpower the portrait. The same cannot be said for the Italian artist Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato, whose painting The Virgin in Prayer shows lapis lazuli at its fullest potential. As Walter Benjamin argues in his essay “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” ultramarine possesses a quality that has to be experienced in-person and cannot be adequately communicated through copies.

Grinding mummies to make brown

Mummy brown is a brown pigment that was made not by grinding up gemstones but Egyptian mummies. The pigment became popular during the 16th century, when traders had constructed a well-oiled network for trafficking mummies into Europe. Human mummies yielded the best pigment, though in their absence, artists also made do with the mummified cats buried alongside their Egyptian owners.

The pigment was popular with Renaissance painters as well as the pre-Raphaelites, a reactionary movement that rejected the idealization of classical art in favor of a more naturalistic approach. In spite of their differences, both groups valued mummy brown for the same reason: It was a highly transparent pigment that worked wonders when glazing canvases and painting shadows and flesh-tones.

In the 19th century, painters slowly fell out of love with mummy brown. This development was spurred by two developments, one financial and the other cultural. According to the British chemist and painter Arthur Church, one Egyptian mummy could produce 20 years’ worth of paint. Despite that, centuries of avid painting had caused the number of mummies on the market to plummet, amping up the price to the point that most painters could no longer afford the pigment. Additionally, the more artists learned about the origins of mummy brown, the less willing they became to use it, as they saw the practice as destroying another country’s cultural heritage and desecrating an individual human life.

For these reasons, the painter Edward Burne-Jones, who had long used the pigment to coat his paintings in a warm, fantastical haze, is said to have buried his tube of mummy brown in the yard, never using it again. Painters can still buy mummy brown in the store today, though it is now made synthetically — and is mummy in name only.

Another kind of costly paint

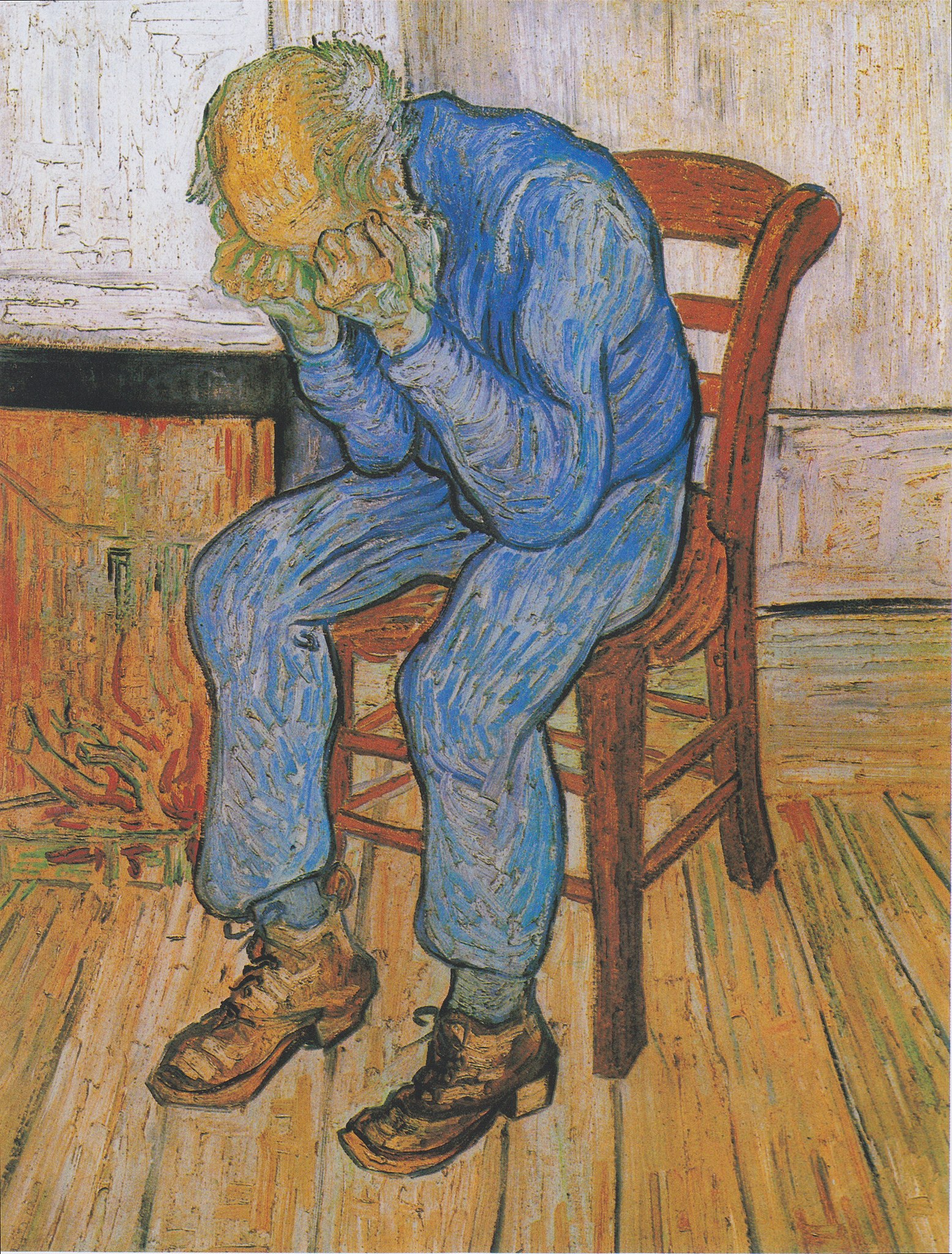

Some people paid for their pigments with their lives instead of money. Painting used to be a dangerous profession, as we now know that many of the paints contained toxic substances, like heavy metals. The Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh died by shooting himself in the chest with a revolver while painting in a field. His tragic suicide was brought about by a lifelong battle with mental illness that, some historians suspect, might have been exacerbated by lead poisoning, a condition whose symptoms — anemia, abdominal pain, and seizures — the painter frequently exhibited.

Like other artists of his time, van Gogh used paint containing high amounts of lead, including lead carbonate and lead chromate. Unlike other artists of his time, van Gogh used this paint in extremely large amounts, slathering color on his canvas to create the vibrant images we know him for today. Van Gogh is also believed to have habitually licked his brushes, making it likely he contracted lead poisoning at some point in his life.

You don’t have to be a painter to get sick from pigments. Just being in close proximity is often enough to do the trick. This, historians believe, may have been the case for the French conqueror Napoleon Bonaparte, who, while confined to the island of Saint Helena, used to take long, hot baths in a room covered with Scheele’s green pigmented wallpaper.

Scheele’s green, as one might suspect, is no longer being used today because it presents a health hazard. The pigment contains arsenic, which can be inhaled as particles flake off. Also, when exposed to humidity, for example inside a bathroom, it can facilitate the growth of a mold that produces the toxic and carcinogenic arsine gas (which also contains arsenic). Napoleon died of stomach cancer, and a toxicology report later found that his hair follicles contained high levels of arsenic. Perhaps one of the world’s greatest military leaders was felled by wallpaper.