Machu Picchu has changed Peru — for better and for worse

- Machu Picchu is one of the most visited tourist destinations on the planet.

- Thanks to its popularity, the Inca city has become the economic and cultural center of Peru.

- However, popularity also has affected the region in several negative ways.

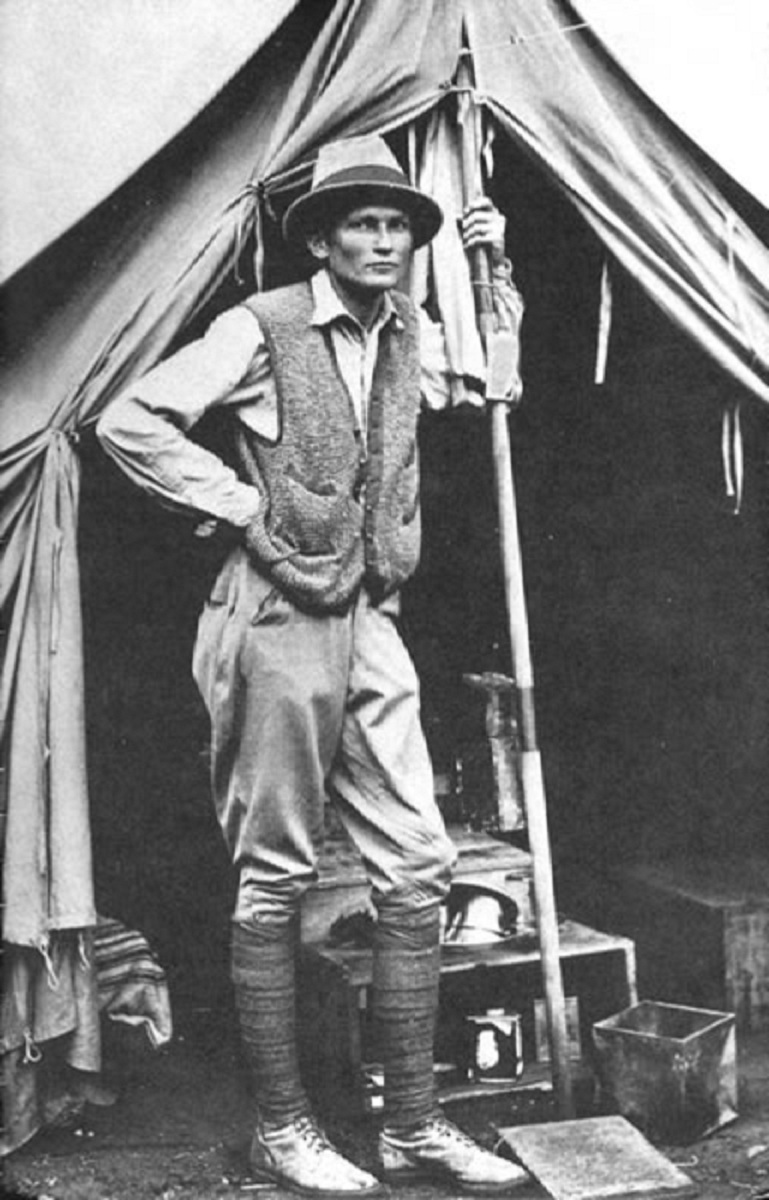

Counted among the New Seven Wonders of the World, Machu Picchu is one of the most visited tourist destinations on Earth. For centuries, however, the existence of the abandoned Inca city was known only to a small number of Andean villages. It was “rediscovered” in 1911 by an American named Hiram Bingham. Bingham, a politician and explorer, originally ventured into Peru in search of Vilcabamba, the fabled stronghold from which the Incas made their last stand against the Spanish Empire.

Bingham never found Vilcabamba, but he did find Machu Picchu. The ruined city, hidden between the mountaintops, consisted of more than 150 buildings, all of which have been incredibly well-preserved. Because the Incas did not have a written language, it’s difficult to say why Machu Picchu was originally constructed. In fact, we don’t even know what the Incas themselves used to call it; the name “Machu Picchu” — Quechua for “old peak” — refers not to the city itself but to the mountain on which it rests.

The prevailing hypothesis is that Machu Picchu served as a scenic getaway for emperors and noblemen. Some archaeologists believe that the ruins were once used for religious purposes as well. The city contains at least two temples: one devoted to the sun, another to the condor, a bird worshiped throughout South America. Machu Picchu’s warm climate also promoted the cultivation of maize, which the Incas fermented to produce a ritualistic drink called chicha.

In an article written for Archaeology, cultural anthropologist Lynn Meisch considers the possibility that Machu Picchu was neither a political nor spiritual center of Inca civilization, but one of several outposts overlooking the Urubamba River Valley. This explanation is supported by research. Funded by Yale University and the National Geographic Society, Bingham unearthed a road system connecting Machu Picchu to other Inca ruins in the area, notably the more distant capital city of Cusco.

Environmental destruction in the Andes

While the historical significance of Machu Picchu remains up for debate, its importance to contemporary Peruvian society is as obvious as it is indisputable. As early as 1948, Bingham noted that the city had “become a veritable Mecca for tourists. Everyone who goes to South America wants to see it.” In 1985, says Meisch, 100,000 people traveled to Machu Picchu via train, while an additional 6,000 chose to complete the journey on foot. By 2019, the total number of visitors had climbed to 1.5 million.

Machu Picchu has become a cornerstone of Peru’s economy, creating countless formal and informal jobs and bringing in an estimated $40 million per year in entry fees alone — much more if you take into account auxiliary expenses related to transportation, hospitality, and food. That said, the increasing popularity — not to mention profitability — of the Inca city is also causing its fair share of ecological, political, and socioeconomic problems for the country.

Although visitors provide the funding necessary to maintain Machu Picchu, their ever-growing presence risks harming the city as well as the environment. “Vibrations from thousands of pounding feet are loosening walls,” Meisch warns. “Tourists venturing off the paths erode the soil.” In 1982, archaeologists had to rope off the city’s Intihuatana — a functioning astronomic clock — because people kept climbing it, carving their initials into its surface, and chipping off bits of rock to take home as souvenirs.

Hikers also contribute to the destruction. Traveling through the national park on their way to the city, they dig latrines, pollute streams, and leave behind large amounts of trash. At times, they have been known to turn Inca structures into makeshift shelters. Alberti Miori, a Cusco-based guide quoted by Meisch, laments the gradual disappearance of the queñoa tree. This tree, native to the Andean highlands, is often used as firewood.

More efforts are being taken to reduce environmental damage today than in the previous century. Machu Picchu’s integrity is monitored by several international organizations, including UNESCO. Hiking trips have become more regulated: porters cook with kerosene stoves instead of plant life, and trash is rounded up whenever travelers get moving. People living inside the national park are still allowed to set up fences and let their animals graze on archaeological sites — but that is another story.

Machu Picchu as the center of Peru

To protect Machu Picchu, the number of yearly visitors must be reduced. However, this is easier said than done, as many Peruvians have come to depend on the city for their livelihood. Whenever the government tries to reduce admissions to the park, Cusco’s tourism industry responds with demonstrations. “We demand the sale of tickets at the offices of the Ministry of Culture of Machu Picchu,” merchants told AFP in August 2022, “to reactivate our economies.”

These merchants suffered heavily during the pandemic, which saw visitations drop by half and never fully recover to pre-COVID heights. The arrest of former president Pedro Castillo is not helping either. News of deadly protests and never-ending roadblocks is keeping foreigners out of the country. As food supplies go down, gas prices shoot up. According to the New York Times, nearly 20% of children under age five in the department of Cusco are suffering from chronic malnutrition.

As mentioned, Machu Picchu has created a lot of work in and around Cusco. Unfortunately, it hasn’t created enough of it. For every tour guide and taxi driver there are dozens of unlicensed street vendors, shoe shiners, and beggars fighting for the right to earn a living, usually to no avail. Not too long ago, Cusco’s mayor sought to expel these vendors — many of whom belong to Indigenous communities — from the city center because they “intimidate” tourists.

Tourism inevitably leads to commodification of culture. This is true for many places in the world, and Peru is no exception. In her article “The Intersection of Gender and Ethnic Identities in the Cuzco-Machu Picchu Tourism Industry,” Annelou Ypeij explains how Indigenous women alter their appearance and behavior in order to match the expectations of tourists. They walk around in brightly colored clothes accompanied by baby goats and llamas, inauthentic qualities that make for deceptively authentic photos.

“Local reactions to tourism,” Ypeij states, “are mixed.” On the one hand, tourists are a source of money — good money, relatively speaking. On the other, their presence alters Peru’s economy in a way that robs locals of cultural as well as political agency. Vendors, shoe shiners, and women posing for pictures, Ypeij continues, “should be seen as individuals who want to be included in the national tourism project and who work hard to reach that goal.” Alas, the system is not set up with their wellbeing in mind.